Life is rich with irony designed to make you smile or wince. Sometimes both.

Flatbed trucks rolled into the Pemberton Valley early on May 18, carrying dozens of portable toilets destined for the site of the 2017 Pemberton Music Festival (PMF). All were meant to be placed in situ two months before they would be needed by thousands of music fans, from July 13 to 16.

They didn't stay, but perhaps they serve as an apt metaphor considering all the crap left behind by the festival's untimely downfall.

As Pique's entertainment writer, I was at home that morning trying to set up my first profile interviews with Pemberton performers.

There was a flurried email exchange with the California-based communications company representing festival organizers Huka Entertainment. While an interview with headliners Muse or Chance the Rapper wasn't likely, I left for work fairly certain I'd have a good story for the following issue.

In the office, the rumours of trouble at PMF were already swirling. I thought it was simply gossip, telling my colleagues I was about to interview a Pemby Fest musician for the following week.

I was wrong. Credible information came in suggesting an announcement on the festival's collapse was imminent; I emailed the same communications people to ask about it.Silence.

So I started to call others, looking for answers. It was four hours before the official response came through.

And since Pemberton Music Festival Limited Partnership (PMFLP) filed for bankruptcy that day, the story that has unfolded has been one of losses, anger and recrimination. Trying to unravel it has been tricky, confusing, and filled with legal jargon, with more questions than answers.

The gory details

Losses amount to millions for some, and thousands for local businesses and contractors. And, unusual for the industry, thousands of ticketholders were not offered automatic refunds, contrary to the usual practice for failed music festivals.

The events that followed PMF's bankruptcy are worth recapping.

Accountancy firm Ernst & Young (EY) was immediately named trustee over the bankruptcy company on May 18; EY's first job was to create a press release for people like me.

Monies owed to secured and unsecured creditors for the 2017 event (which included some debts left over from previous years), totalled $16.7 million, including millions owed to ticket purchasers.

An info sheet provided by EY with the announcement cited the weakened Canadian dollar and trouble sourcing talent for 2017 as factors contributing to the collapse. It suggested that a poor lineup had a negative impact on ticket sales, though tickets went on sale a month later than in 2016, which couldn't have helped the situation.

The ensuing public shock and anger was immediate. On social media, where fans had previously raged at PMF over wait times for buses, or against coy online comments by Huka PR staff, the reaction was apoplectic.

The festival's website — on which tickets ranging in price from $299 to $1,799 were sold via Ticketfly — eventually came down, although tickets were still on sale hours after the bankruptcy was announced.

A Statement of Affairs released by EY listed 130 creditors, two secured (1644609 Alberta Ltd. and Janspec Holdings Ltd. — owned by Canadian investors) and many more unsecured creditors, including local companies and individual contractors, as well as government bodies such as BC Hydro and Canada Revenue.

And around 18,000 people were owed over $8.2 million in total for tickets purchased for July.

On June 6, the first creditors' meeting took place at the downtown Vancouver campus of the University of British Columbia. About 20 people turned up, mainly creditors and their lawyers. Further details of the losses released there were even more astonishing, as outlined in the Report on the Trustee's Preliminary Administration handed out at the meeting.

It showed that the resurrected PMF failed to make a profit at any point in its four years of existence; despite ticket sales increasing every year and Huka's own positive projections, millions of dollars were lost per annum.

At the creditors' meeting, EY stated that PMFLP and one of its parent companies at the time of the collapse, 1115666 B.C. Ltd. (directors were Canadian investors Amanda Girling and Jim Dales, and Huka representative Stephane Lescure), had assets of around $3.3 million in cash.

It would not be nearly enough to cover the claims.

And although it was expected the secured creditors would be the first to be reimbursed, Janspec Holdings Ltd. and 1644609 Alberta Ltd., owed $3.6 million between them, waived their right to be repaid.

The festival itself lost investors $16.9 million in 2014, $16.8 million in 2015, and $14 million in 2016, more than $47 million altogether. The 11-page report told the tale of a soured relationship between Huka and the Canadian investors. EY trustee Kevin Brennan described Huka as difficult to communicate with, saying they provided "no satisfactory response" to an EY request for financial records.

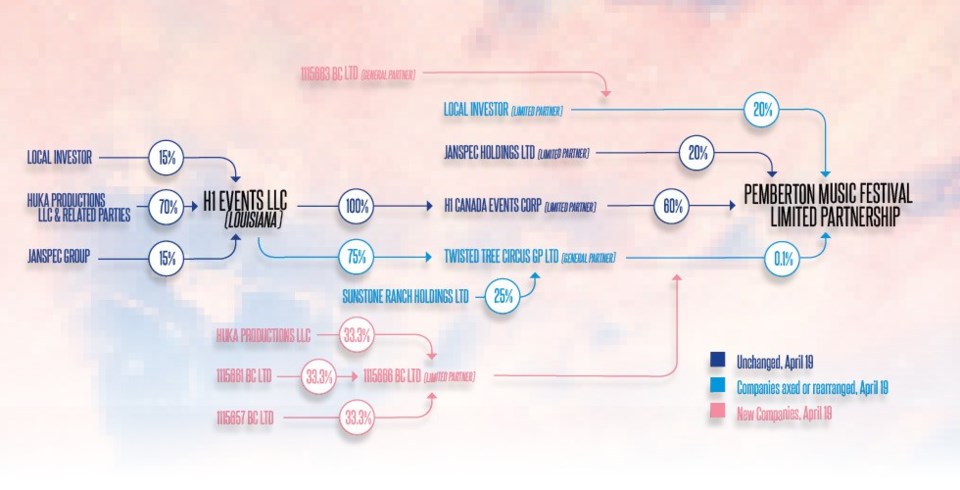

The report included two appendices that showed the various U.S. and Canadian holding companies involved in PMFLP. (See page 31)

The first graphic in the report represented the ownership labyrinth over much of the history of the festival, with nine investment and holding companies linked to PMFLP owning various percentages of the company. Those involved included Girling, Dales, and Lescure, along with Huka's chief experience office A.J. Niland and CEO Evan Harrison.

That set-up was changed just prior to bankruptcy being declared, something that continues to trouble music industry onlookers, creditors, and the general public.

On April 19, Twisted Tree Circus GP Ltd. (Niland and Harrison) was replaced as a general partner in PMFLP by 1115666 B.C. Ltd. (Dales, Girling and Lescure).

Vancouver bankruptcy lawyer Geoffrey H. Dabbs told The Vancouver Sun, "It's odd that you'd switch general partners a month before your bankruptcy."

In a June article, New York Times' Ben Sisario wrote that Pemberton's downfall could have a bigger impact than the recent high-profile collapse of the Fyre Festival in the Bahamas, in part because of the lack of transparency leading up to the bankruptcy.

Scheduled over two weekends in April and May, Fyre Festival organizers ran into a litany of logistical issues before hundreds of people arrived on the private island only to find it was nowhere near ready to host the luxury event they had forked out over hundreds of dollars to attend. It was promptly cancelled.

Fyre is now the subject of eight lawsuits, one seeking $100 million in damages, which all accuse Fyre organizers of defrauding ticket buyers.

Fyre co-founder Billy McFarland was arrested on June 30 on charges of wire fraud.

So far, the situation for PMF is less dramatic; an RCMP spokesperson said there has been no investigation into the festival's bankruptcy claim, adding that law enforcement would only get involved if there were some indication of criminality, such as fraud.

Huka and the Canadian investors

Pique tried several different avenues in an attempt to secure an interview with representatives from Huka. They did not respond.

But the company broke its silence for the first time since May 18 in a Statement of Facts sent in to EY on June 23 via its Vancouver lawyer Jonathan L. Williams. The statement expressed outrage at the June 6 trustee's preliminary administration report.

Unsurprisingly, Huka objected to many of the assertions laid out by the trustee. The company requested 35 corrections to statements in the report, calling certain points "beyond misleading," and "completely untrue and outrageous."

Huka took particular issue with who lost money, saying it never took funds without permission from investors, and described itself as "conservative and guarded in its financial projections." (The company forecasted profits in 2014 and 2015, and expected to break even last year.)

The Statement of Facts posited that Huka did everything it could to spare the event from disaster before Girling, Dales and Lescure voted to file for bankruptcy. It even claimed that Huka had secured a Letter of Intent from a "high net worth investor" who was prepared to "immediately provide funds sufficient to allow PMF (20)17 to proceed" and would move the festival's location in order to reduce costs. The Canadian investors appeared to ignore this, according to Huka. The company believes it should be considered alongside the Canadian investors who lost millions over the last three years.

"Huka was so unwaveringly opposed to any result that would cause (the PMF) to fail to honour its commitments, that it delivered a letter of resignation to everyone who was present at the vote related to the insolvency," the statement said. "That letter was read prior to the vote, and specified Huka was immediately resigning, unless the Canadian investors agreed to honour (the festival's) commitments to ticket holders and artists."

The gravity of this was understood by the Canadian investors, Huka claimed, as they offered refunds to select ticketholders who purchased passes from The Meadows at Pemberton Golf Course, which is owned by one of the Canadian investors.

There are many other rebuffs and explanations in the 16-page statement, including Huka's contention that the trustee's report characterized Girling and Dales as being removed from the operation of the festival.

"The Canadian investors were both investors and operational partners from the outset," according to the statement.

"This included day-to-day involvement in producing the festival and complete access to books and information."

Huka said that both Girling and Dales were privy to all financial documents and information.

"Moreover, the Canadian investors always did their own 'due diligence' and then repeatedly invested funds, after weighing the risks and benefits," the statement read.

Speaking for the Canadian investors, Janspec VP Nyal Wilcox said in an email that they had no comment on Huka's response, adding, "the information in the Trustee's original report was based on facts."

Wilcox would not comment on whether any litigation was planned against Huka.

When asked why the Canadian investors continued to pour money into the event, he wrote:

"In the first three years, Huka continued to be confident that they would improve the bottom line and attract other investors. Neither happened and the losses could no longer be sustained."

Enter Ticketfly and the courts

After June 6, the resolution process between Huka and the investors came to a crashing halt, with Ticketfly taking the matter to court.

Ticketfly turned down an interview request to discuss the collapse of PMFLP and the pending court case, but as trustee, EY answered the same questions.

In the ticket-purchasing process, a credit card company such as Visa or Mastercard would buy the ticket on behalf of a cardholder, passing on the payment to Ticketfly. When Pemberton failed, the credit card companies, which typically have agreements to reimburse purchasers in the event of bankruptcy, have been paying out to disappointed ticket holders, and turning to Ticketfly to reimburse them.

EY's Brennan said in an email that Ticketfly is asserting a constructive trust claim, an equitable remedy typically imposed by a court to benefit a party that has been unjustly deprived of its rights. If the claim is deemed valid, the court will determine the amount of funds to be paid over to Ticketfly.

No date has yet been determined for the court proceedings.

Ticketfly was caught in a difficult position following the bankruptcy. The American company served as the sales agent for the Pemberton Music Festival, with its automated system directly linked to the festival's website.

As of June 6, Ticketfly is claiming at total of $7.9 million (with chargebacks of approximately $2 million); this number may change once its claim is fully filed.

After the case is concluded, it's expected none of the money owed to unsecured trade creditors and those ticketholders that were unable to secure a refund through a credit card company will be recovered, Brennan added.

Taking Pemberton's pulse

It has been estimated that PMF brought over $200 million to the Pemberton region over the three years it was staged.

"We're into July now and I think the community is feeling a bit of a void; we're normally starting to gear up for the festival. The work would have started on the site and the buzz would be going around," said Mayor Mike Richman two weeks ago.

The collapse has remained the talk of the town, he added.

"The economic loss is huge, you know, the lead-up to the event, the teardown of the event, it brought so much activity to the area. Those things on their own had a ton of spin-offs. And on the weekend of the festival, there'd be 40,000-plus people in the valley (each day)," Richman said.

He listed opportunities for local businesses to profit, and employment for workers.

"People have asked me what Pemberton is going to do. It's sad and a huge loss, but we're not closing the doors. Pemberton is so busy in the summer these days. Tourists are coming."

Richman said he hasn't heard anything from Huka or the Canadian investors since May 18.

"It's been pretty quiet," he said.

"We're the host community — we do the permitting and make sure it's safe and makes sense on those levels. We don't get involved in the business aspects of it... just like we don't get involved with other businesses."

He likened not knowing the business health of the backers of PMF to not knowing the books of the local restaurants in town.

Across the village at Grimm's Deli, owner Mark Mendonca talked about the financial commitment he made in taking his company onsite at PMF to serve food. In the first year of the event in 2014, he hired 20 extra staff at $20 per hour, worked 22-hour days over the weekend, and made considerable investments in equipment. He now has a portable restaurant set-up that he hasn't used since last year's festival.

He made sure his success came from supporting local staff and suppliers. For one thing, last year they sold fries made from 2,270 kilograms of local Pemberton potatoes purchased from the nearby Kuurne Farm.

"Small businesses have to look for all the opportunities that they can take advantage of. We were asked to be a local company onsite. We discussed it in the family and decided it was something we could do," he said.

Mendonca stressed that he is not an unsecured creditor in the bankruptcy proceedings.

"To go forward, we needed to make an investment in equipment — the booth had to be certain specs, the flooring, etc. There's a very large investment in that. And we had to bring refrigeration onsite. We had fryers and tables, too," he said.

"We were looking at it as a long-term investment."

Mendonca said they suffered a "pretty big loss" in year one ("a learning experience"). In the second year, things improved for Grimm's thanks to a better location, and they did well in year three as well. Over the three years, he said they broke even.

Mendonca, who is also the executive director of Tourism Pemberton, had been working alongside Huka's Niland and his team on an application to Destination BC for a Works and Skills Grant for $300,000 to "put Pemberton on the map at the festival and showcase the community onsite." In this, he had nothing but good to say about Huka's assistance in pulling the application together and getting the information required.

The plan was to create tourism videos to run on the large screens at the festival, and offer daily prize draws for trips that would take selected festivalgoers and their friends to the top of Mount Currie by helicopter.

"It is tragic. We invested 40 long hours, with calls to the different groups. The amount of information we had to pull together," Mendonca said.

"I can't see how A.J. would have gone through all this trouble (if he thought the festival would fail)."

The application was sent in on May 17, the day before PMFLP declared bankruptcy.

Mendonca described the festival as an advertisement opportunity they could never afford otherwise.

"The festival put us on the map. We had 40,000 people per day, with the majority knowing nothing about Pemberton prior to the start of the festival. You do that over three years and that is hundreds of thousands who learned about us. We couldn't have bought that kind of exposure," he said.

The music industry

South of the border, representatives of the music industry looked on with incredulity and anger as the bankruptcy unfolded.

Marc Geiger, a co-founder of Lollapalooza and head of William Morris Endeavor's music division in Los Angeles, had expressed his anger on the record early on in Billboard, particularly on behalf of powerless ticketholders.

Several of his clients, including Haim, Big Sean, and Tegan and Sara, were scheduled to perform at PMF.

As more information on Pemberton's collapse came to light, he said in an interview he remained furious.

According to Geiger, the industry found Pemberton's bankruptcy to be such a big deal because of the issue of potential consumer fraud. Bankrupt festivals should not rip off consumers, he added, no matter what caused the event's failure. He called the behaviour of those behind PMF very unusual.

He was incensed by the actions of a number of players in the PMFLP case, particularly Huka and the Canadian investors, in the lead-up to the bankruptcy, calling it worse than the Fyre Festival's failure, because at least organizers tried, albeit in a catastrophic fashion, to ensure the event went ahead.

Geiger also contrasted it to the actions of festival organizer Live Nation, which had founded the first Pemberton Festival in 2008, but pulled out owing to losses that were not passed on to the consumer. Live Nation did the same thing when they shut down the Squamish Valley Music Festival in 2016 before tickets for that year went on sale.

Geiger said he was horrified by the PMF situation, particularly that the Canadian investors didn't solve the situation in a business-like manner.

He also explained in detail how he believed the transactions between the investors, Huka and Ticketfly, played out. Geiger was critical of Ticketfly and its decision to forward the money to Huka on request, believing they did so because the latter had been cut off by investors and Ticketfly wished to help their client. Normally, Ticketfly would hold onto funds from purchasers. Ticketfly was then left in the lurch when the festival failed.

Geiger said ticket sellers needed to honour consumer transactions first and foremost, adding that refunds to Pemberton's ticketholders are in order.

The future

Despite everything, there has been some talk of taking over the PMF brand. The logistical challenges of the past three festival weekends, from moving thousands of festivalgoers around, to traffic and parking, to drug testing, to camping, is useful business knowledge waiting for a new organizer or production company to run with it.

But Pemberton's mayor said there is nothing solid at this point.

"There is discussion. The door is wide open, the venue has been proven, so let's see what we can come up with," Richman said.

"Huka put in a lot of the groundwork. And the site itself — there aren't many where you can draw a circle around an entire site and keep it almost self-contained. I like to think that there will be a bit of a reinvention of the festival, if we do pull in another production company."

Whistler resident Liz Thomson runs the Bass Coast Electronic Music and Art Festival, now in its ninth year in Merritt.

The festival, which took place from July 7 to 10, sold out in December and is considerably smaller than PMF with 4,500 tickets sold in 2017.

"I think that is why we have longevity. We could have sold three or four times as many tickets as we did, but we cap it and sell out in order to keep the experience intimate," Thomson said.

"Pemberton had a different core value and business structure from this."

Thomson said she has worked closely with Huka on more than one festival — including the Tortuga Music Festival in Florida — through her second company, The Guild, which builds monumental art displays such as the artificial trees that stood at the entrance to PMF in 2016.

She spoke of the staff layoffs Huka experienced as a direct result of the PMF collapse, saying that some Huka managers had no idea PMF was in trouble until the first news story came out.

Huka's CEO confirmed the layoffs to Billboard on May 26, eight days after the bankruptcy, but would not say how many employees had been let go.

"The greatest impact (of the bankruptcy) was on ticketholders, that is the sad part. But there was also a huge impact internally; a lot of talented, hardworking people had no idea." Thomson said.

As Thomson sees it, the smaller, more intimate festivals become stronger in B.C.'s music festival landscape, while the large festivals come and go.

"There's a big difference between a concert and a music festival — the difference is the experience. Big concerts are fundamentally flawed and small festivals have a connection. We sold out before our lineup was released. That speaks volumes," she said.

Thomson said that the Sea to Sky region needs to consider why both the Squamish and Pemberton Festivals didn't succeed.

"It's such a good thing for communities, but maybe it's time to look at deeper reasons why these festivals are failing," she said.

To read the documents referred to in this feature, visit the Ernst & Young website at http://bit.ly/2tyCHl8.

Pemberton music Festival LP Before and After April 19

The graphic shows the complex business arrangements running the Pemberton Music Festival before and after significant changes were brought in on April 19, 2017, a month before the bankruptcy of Pemberton Music Festival Limited Partnership (PMFLP) on May 18.

The following companies shown in dark blue were in place during the running of previous festivals and were unchanged until May 18.

They are "Local Investor," Canadian Jim Dales, Louisiana-based Huka Productions, and Janspec Group, owned by the Canadian Girling family. They respectively owned 15%, 70% and 15% of H1 Events LLC, a 100% shareholder of H1 Canada Events Corp., which owned 60% of PMFLP.

Janspec Holdings, a separate entity to Janspec Group (see below), but still owned by the Canadian Girling family, had a 20% limited partner in PMFLP.

H1 Events LLC was also a 75% shareholder of Twisted Tree Circus GP Ltd. until Twisted Tree was removed on April 19.

The following companies shown in light blue were axed on April 19.

Twisted Tree Circus, largely owned by Huka, owned 0.1% of PMFLP until April 19 — it was replaced by new company 115666 BC Limited, the new general partnership with three directors, Amanda Girling, Dales and Stephane Lescure; Sunstone Ranch Holdings Ltd., a Janspec company, was removed as a 25% partner in Twisted Tree Circus and not replaced; "Local Investor" Dales was replaced by 1115663 BC Ltd., also owned by Dales.

The companies shown in pink were new companies created on April 19.

They are 115663 BC Ltd., owned by Dales, which held 20% of PMFLP from April 19 to May 18; 1116661 BC Ltd. and 1115657 BC Ltd., which each owned 33.3% of 1115666 BC Ltd. And Huka Productions, which was already in existence (see above), was also brought in to own 33.3% of 1115666 BC Ltd. The latter company replaced Twisted Tree Productions, and owned 0.1% of PMFLP from April 19 to May 18.

On May 12, 2017, Girling, Dales and Lescure ceased to be directors of 115666 BC Ltd., according to a change of directors notice filed on May 17, the day before PMFLP declared bankruptcy.

Asked if such business set-ups are common, Kevin Brennan of Ernst & Young wrote in an email: "Yes, a general partner and limited partnership set-up are common, as are various holding companies to hold the respective interests."

Source: Ernst & Young