On an unseasonably warm February day 17 years ago, Julie Smith died.

Riding on Mount Seymour in spring-like weather, the 32-year-old was on a run she had done countless times before, and just at the point where she started to pick up some speed, she caught the heel-side edge of her board and fell backwards, her skull bearing the brunt of the impact. She wasn’t wearing a helmet.

At Lions Gate Hospital, a social worker pulled her husband aside and, in hushed tones, told him the news no loved one wants to hear: Julie might not make it.

On a chilly December day five years ago, Kody Williams died.

The 23-year-old pro snowboarder was filming a session in Stanley Park, where he was riding a rail on a wooden staircase, when he fell and struck his head. He wasn’t wearing a helmet.

Drifting in and out of consciousness, Kody was rushed to Vancouver General Hospital, where his mother remembers a doctor ushering the family into a small conference room. He drew a diagram of the head injury and explained the challenging surgery that would temporarily remove a part of Kody’s skull. Afterwards, he would be placed in a medically induced coma.

It wasn’t clear whether he would survive the devastating brain injury, let alone walk, talk or ride again.

“It was a lot of wait-and-see, a lot of pacing the walls, going to the chapel,” Kody’s mom, Jocelyn, told Pique in a 2020 interview. “A lot of tears, a lot of silent moments.”

‘I did die that day. My body didn’t and my soul didn’t, but I did’

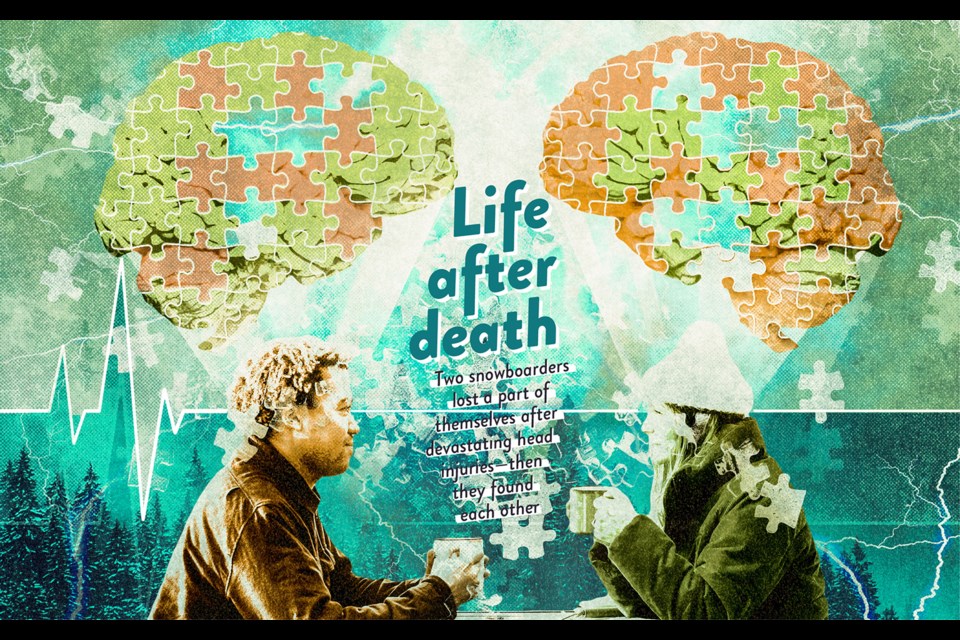

Sitting here in Cranked on a bright December morning, cappuccinos steaming in front of us, Julie, now 49, and Kody, 27, are very much still alive. But both of them maintain an essential piece of themselves was lost on the day of their respective accidents, a dozen years apart.

“I did die that day. My body didn’t, and my soul didn’t, but I did,” Julie says. “And as much as I kept trying to be here, I was just failing all the time. So I felt shitty all the time. I felt like a fraud and I felt like a fake, because I’m showing up as Julie, but she’s not there.”

It’s something you hear from many people who have suffered traumatic brain injuries—or TBIs, as they’re known: physically at least, you appear the same as you always have, but internally, you’re anything but.

“People think you’re fine on the outside but you’re still reflecting on yourself and figuring out how you are, personally,” Kody says. “It’s different all the time for me. There’s good days and bad days. The smallest things can trigger me sometimes. Not in an aggressive way. Onto myself. It’s hard to explain.”

Both Kody and Julie can’t remember huge chunks of time both before and after their injuries, and pretty much everything they know about their lives from that time has been relayed to them by someone else. Julie still doesn’t recall the births of two of her sons. When I first ask Kody his age, he hesitates, initially unsure of the answer.

It makes any kind of long-term planning an obstacle, and means even the simplest tasks have to get written down to jog the memory—although, as Kody joked, even remembering to do that can be difficult.

I say it reminds me of Memento, the 2000 Christopher Nolan thriller about a man with a rare form of amnesia who uses an elaborate system of Polaroids and tattoos to remember key memories in his quest to avenge his wife’s murder. Julie prefers the comparison to a much lighter film.

“Have you watched 50 First Dates?” she asked. “Adam Sandler and Drew Barrymore, that was my husband and I. He would leave the hospital room. He’d go to the coffee shop because he was exhausted. He’d come back and I’d be like, ‘You haven’t been to see me in days.’ He was like, ‘I literally left five minutes ago.’”

The irony is the one event that has altered the course of their lives more than any other is also the one they will never remember. Their accidents live like ghost stories inside them, told and retold by friends and family who have no interest in reliving them. For years after her fall, Julie would ask her husband again and again to tell her what happened that fateful day, poring over every small detail.

“All I wanted to do was link it, and say, ‘Babe, tell me the story again.’ And all he wanted to do was forget the story. So it was brutal, because he was the only piece linking me to it. And yet I’d forget anyway. So then he had to keep reliving it,” she says. “Meanwhile, the person over here, us, we’re sitting here getting lonelier and lonelier. How the hell do I not remember that? How do you die on a mountain, come back and yet you don’t remember? How does that even happen?”

Like Julie, Kody has had to rely on the recollection of friends to piece together what happened that day five years ago, but he did have a flash of memory when he happened to be walking though Stanley Park last summer and a strange sense of déjà vu came over him.

“We were in Stanley Park and we were just walking and, I dunno, I saw the rail and had this weird gut feeling,” he says.

Kody texted a photo of the rail to a friend who had witnessed the accident. “He was like, ‘Holy shit, that’s the rail. How did you know?’ I just had a feeling. No one’s been back to that rail since that day, other than myself, and I just stumbled upon it.”

Born again

At home with three kids, unable to drive, unable to do so many of the things that used to make her who she was, Julie spent the first three years post-accident in an identity crisis, living a pantomime of her past self.

It got to the point where she woke up one morning and decided she needed a change. But first, she needed to grieve the loss of the old Julie.

“I felt strongly I had to go back to Seymour and reckon with her. I call it a reckoning. I had to reckon with her,” she explains.

Despite her family’s objections, Julie decided she needed to ride the same run that had been the scene of her crash three years prior, and she needed to do it alone. The conditions were approaching blizzard-like, and as Julie began the descent, she started to scream and cry out loud, first at the mountain. You’re not going to take me! she remembers yelling. Then she began talking to herself. Or at least the self she used to know, the Julie she pictures as a baby hanging around her neck, slowly suffocating her.

“That day I physically took her hands out from my neck and I put her in my own hands, like this, like a baby Julie, and I looked her in the eyes, and I told her it was time to go. And I let her go,” she says. “I stood there and I cried for a while. Because there are parts of you that don’t want to let her go. But I can tell you that that was the day I received more freedom from my own self, and in giving myself permission to feel free, it allowed others to see me differently, whether they liked it or not.”

Grieving her past self also came with an acceptance of who the new Julie had become.

“What this has forced me to do is find out the essence of Julie. What is my essence? What did I show up in the world as before I hit my head? What were the healthy things? The not-so healthy things?” she says. “When I tapped into that, I was like, ‘Well, I know I love people. I know that I bring light to the world. I know that I love to laugh. I know that I’m compassionate.’ And so when I started to tap into who I was, that whole rebirth helped me fall in love with myself. I’ve never loved myself more in my whole life.”

Nearly five years from his debilitating accident and Kody admits he hasn’t yet reached the point where he’s quite ready to grieve the loss of his past self. Where Julie is self-possessed and almost radically honest, Kody is less sure of himself, guarded. He is, by his own account, still figuring out what the new Kody is all about, while reconciling the parts of himself that have been irrevocably changed. The head injury left him with epilepsy, for instance, which means he has to take a cocktail of pills every day to stave off potential seizures, a new facet of his life he is still working through.

“I’m still trying to figure myself out, I guess. It’s something I do need to work on more,” he says. “I hate taking those pills but I have to take them because it’s just who the new Kody is and it’s something I have to do. I still need to accept that this is something I’m going to have to take, it sounds like, for the rest of my life. It frustrates me but it’s not doing anything but making me the new me.”

Kody has experienced a rebirth of sorts, though. After having to relearn how to walk, talk and even chew, doctors never expected he would ever ride a board again. But, like he has so many times since his life-altering accident, Kody defied the odds. In the 2020-‘21 winter season, he got back on snow, and all he can remember from that day is smiling. Lots of smiling.

“What pushes me the most is probably when they said I wouldn’t ever be able to walk again. So being able to snowboard again and ride the way I’m riding is kind of an eff you to my injury. It’s me beating my injury,” he says.

When we meet, it’s only days before the fifth anniversary of Kody’s accident, a day he looks forward to all season.

“This is my favourite day to snowboard for me,” he adds. “Just because I had a 25-per-cent chance of making it through that night, so being able to go and snowboard on the day I almost died, it’s just my favourite day to go snowboarding.”

‘It’s like a soul thing’

Whistler’s snowboarding community being as insular as it is, Julie learned of Kody’s catastrophic injury not long after it happened.

“I obviously didn’t know Kody but that was like a punch in the gut when I heard about his accident,” she recalls.

Fast-forward a couple years, and Julie’s son, Truth, a regular at the Whistler Skate Park, told her about a friend and fellow skater named Kody he thought she should meet. She would see him at the skate park from time to time, but didn’t have the heart to approach him. That is until one day in the summer of 2019, when something inside her told her she had to take the leap. Julie walked straight into evo, where Kody worked at the time, and introduced herself.

“At first I think I was a little shy and then I would open up more to you. Then seeing you at the skate park and seeing you more often, I got very familiarized and comfortable around you,” Kody tells Julie.

Soon enough, plans were hatched to go for coffee, and the two friends have been meeting regularly ever since. Sometimes they dish about their injuries, laugh about their brain hiccups and short memories, while other times, they talk about their shared interests, like fashion or the latest absorbing article they’ve read.

“The injury is what really brought us together and what made the friendship, but we’re more than just two brain injuries,” Kody says.

At times, Julie will slip into mother mode, giving Kody advice on everything from his relationship to his latest filming session.

“It’s funny because my role is as a friend, but then also Whistler mom. It’s like, OK, you’re my friend but also I’m going to mother you a little bit,” Julie laughs.

“It’s always nice having her there. I can reach out to her,” adds Kody. “She is like my mother. She’s always there for me if I call.”

The truth is they don’t even think about their 22-year age gap until someone else brings it up. Even from spending an hour with them, you can tell this is a friendship that defies age. Theirs is a natural, comforting chemistry, the kind that goes beyond just words, a world of emotion shared through a simple glance or knowing nod.

“There are times we don’t even have words because we can’t get them out properly. But I can look in Kody’s eyes on a painful day and know what he’s feeling,” Julie says. “It’s like a soul thing. That’s all I can explain it as. It’s two souls who’ve gone through a really traumatic and difficult thing. And yet there’s an understanding there, and a love and a respect and an admiration.”

Discussing his past trauma hasn’t always come easy for Kody, who admits he has been reluctant to talk with a therapist, despite the urgings of loved ones. But with Julie, there’s no therapeutic playbook to follow, just a mutual understanding that allows him to be whatever he is that day.

“It’s a deeper understanding. A lot of people, nothing against them, but they can say they understand but there’s no way they’ll understand. I can look Julie in the eyes and I know she knows what I’m saying and she’s not just nodding her head,” he explains. “I’ve been told to talk to somebody, but Julie, not knowing who she was at first, I was comfortable just to talk with her because she actually lived it and she’s not just someone there to listen to me talk.”

Risk takers

A few months ago, Julie had a dream. In her telling of it, the dream looked and felt like they were living inside of a movie, a movie called Kody and Me. “It’s just Kody and me and we’re just doing shit,” she describes. Visiting the farmers’ market. Eating snowcones. Walking alongside each other, balloons in hand. A simple, idyllic day— just two friends enjoying each other’s company.

“I woke up and I was journaling about it and I was like, obviously this can’t be a movie. We’re not making a whole movie about Kody and me,” Julie says. “Then I started to think about how grateful I was.”

Two-and-a-half years from that fateful day when Julie walked into evo to introduce herself, and that profound sense of gratitude remains. Gratitude for each other, for how far they’ve come, for the people they are today.

“I think we protect ourselves so much from human connection because we’re so scared. I’m grateful. All I can say is: my gratitude for Kody in my life is so big,” Julie says. “Sometimes you have to take the risk. Sometimes it’s not the norm. And yet both of us were told we would never walk or talk again. So we get to be alive. That’s important. We get to do this life. We got a second chance. How do you want to live it? I tell you what, I’m going to risk it. I’m going to risk having someone say, ‘Yeah, I don’t want to connect with you.’ But I’ll always take the risk now.”