It provides 10,000 times the amount of energy we use on Earth every day. It's free, it's plentiful, it's super-clean and safe—and it's everywhere. The sun may well be our best friend in the face of our fossil-fuelled climate emergency, if only we harnessed it more.

Right now, dozens of countries around the world—China, Japan, Germany, France, the U.S. and U.K., Italy, India, even tiny Latvia, and more—depend on solar power to some extent. Here in Canada, Alberta and Ontario are our solar leaders—Alberta with 25 per cent more sunlight than the heartland of Canada's solar capacity, Ontario, where solar power has proven to be a welcome addition to a power grid that often fails and where people have tired of throwing out the food in their freezers over and over.

Now, that picture could change with more—and more unexpected—places jumping on the solar express thanks to an exciting new innovation developed by researchers at Vancouver's University of British Columbia (UBC), ranked the No. 1 campus in the world for taking urgent action on the climate crisis.

They've come up with a low-cost, sustainable biogenic solar cell made with dye-producing bacteria. It works as well in dim light, like cloudy or overcast skies, as in bright light, like full sun. Even in early stages, the cell generated an electrical current twice as strong as any from similar devices, its capacity is constantly being increased.

Biogenic solar cells using dye have been produced before, but they entail costly, complex processes that use toxic solvents to extract the dye, plus the dye can be lost making the cells less effective.

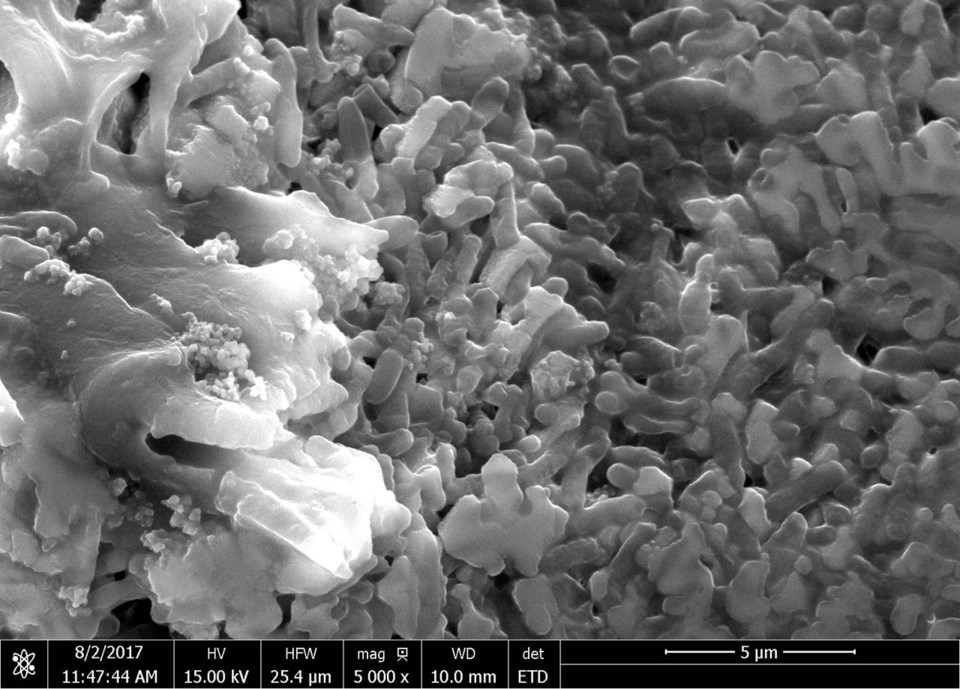

("Biogenic" simply means something made of or produced by living organisms, in this case E. coli bacteria that have been engineered to produce lycopene, a natural dye that gives tomatoes and other red fruits and vegetables their colour. Lycopene is also very good at "harvesting" light and turning it into electrical energy. E. coli are used because they're one of the most productive and versatile bacteria in the lab—and, no, this isn't the type that makes you sick.)

The new UBC approach leaves the dye in place, which makes it higher yielding and about 10 times cheaper. It also uses a nano-coating of titania (or titanium dioxide) to enhance electrical production. The same titanium dioxide used to tint white the acrylic paints in your art studio, it's an excellent conductor.

The result? Bacteria-powered solar cells that are more economical and efficient than comparable biogenic systems, and certainly more organic and sustainable than conventional solar cells made with things like silicone, hydrochloric acid and unrenewable metals, such as platinum.

"It was a shot in the dark, and serendipity helped us a bit," says Vikramaditya Yadav, a professor in UBC's chemical and biological engineering department and the project lead.

Drawing on his own research in bioactive materials and dyes at Harvard and MIT was critical, but Yadav credits most of the serendipity to the creativity and complementary backgrounds of the talented five-person team of graduate students and scientists who comprise his BioFoundry research group, which specializes in collaborating with local start-ups, industry and other researchers on creative, bioengineered solutions using bacteria.

THE PURE JOY OF PURE RESEARCH

"When Sarvesh [Srivastava, a researcher from the Technical University of Denmark,] joined the lab, he was a material scientist. He had never touched biology," recalls Yadav. "But this guy, he was full of energy, and one day he came by my office the start of 2017 and said, 'I have some very interesting ways to synthesize organic materials—metals and metal oxides. I want to spend some time in your group.'"

At that time, the BioFoundry had been looking at lycopene to make nutraceuticals—those hybrid pharmaceutical/food supplements you might buy at Nesters Market or Whole Foods. But Yadav directed the young researcher to work with some fermenters making lycopene, and the moon shot took off from there. It started off like the Toronto Raptors' story: At first things looked dismal, but that quickly turned around.

"Sarvesh would come into the office, shoulders slumped," says Yadav. "He'd made a lot of lycopene, but 'unfortunately' everything was degrading."

Initially, the team wanted to stop the degradation. Then they started asking questions, like, why was it happening in the first place?

It was these informal conversations, literally around a water cooler, where one thing led to another. The team landed on the idea of experimenting with light—bingo! They proved the degradation was occurring because each molecule of lycopene released an electron when light, even low light, hit it. And electrons mean electrical current. As well, Srivastava knew they could take the bacteria and coat them with something metallic (like the titania nanoparticles) to make it more conductive, and they had a winner.

"It takes only a day or so to grow the bacteria and make the dye and coat it, so making this was very, very easy," says Yadav.

In my books, that's exactly the kind of reward that pure, undirected scientific research can give the world.

OFF TO THE RACES

Once they're developed at a commercial level—and several companies have already approached UBC—these unique biogenic solar cells would work effectively in low-light settings such as mines or deep-sea exploration.

But most of the excitement is around their use in places like Vancouver—and Whistler—as well as much of Canada and the northern U.S., northern Europe, the U.K., and parts of New Zealand where cloudy skies are common.

"Any locations where you're depending on solar, it's a game-changer because the hours you can generate power and the amount of power you can generate in non-ideal conditions is so much better."

Rod Nadeau, managing partner, Innovation Building Group

"This is perfect for a place like Whistler ... When you use these materials in overcast conditions where you don't have a lot of energy descending on solar cells, they're able to function as well as they do in direct sunlight," says Yadav, who reminds us he's referring to biogenic cells once they're manufactured as solar panels, which may be only three to five years away.

"It's not like you spent a lot of money and installed a lot of solar panels, and you find out that for most of the year these things are not able to generate enough electricity because it's too overcast," he says. Conventional solar panels do generate electricity under cloudy, foggy or overcast skies, but they average around only 10 to 25 per cent of their rated capacity, depending on the panel and conditions.

"The big advantage here is you get a return on the investment you make on the infrastructure, which is critical for regions that are thinking about solar," Yadav adds.

"Climate change is one argument. But another important argument that often gets buried is you have to still achieve sustainability. There are no ifs and buts—economic sustainability is also equally important.

"There is no unlimited sum you can pay for technology in order for it to be sustainable."

WHISTLER: THE ETERNAL EARLY ADOPTER

Since its early days of hippie-jock blissdom, Whistler's always been a town of early adopters—people quick on the uptake of good, new ideas and ready to push the boundaries.

"Game changer" was the term that came up time and again regarding the new solar cells.

"It's encouraging to me that the flexibility in the [new building] code will allow for adoption of new technology like this one," says Whistler's mayor Jack Crompton, who loves new technology. "As a ski town, we're eminently aware of our need to find ways to reduce our emissions. Whistler is working on ways to reduce our impact and adapt to the climate, and ideas like this are important for us to consider."

"If this new technology can obtain energy comparable to current synthetic [conventional] solar under cloudy skies, as we see in the corridor, that is a game changer. And it's not just clouds, it's mountain slopes. We put a bunch of solar up on a cabin we have at Anderson Lake and it's interesting, because we're on a really steep slope and it has its challenges. It doesn't start picking up until 11 in the morning, when the sun goes over the ridge."

Arthur De Jong, municipal councillor, and Whistler Blackcomb senior manager of mountain planning and environmental resource management

Municipal councillor Arthur De Jong, who has worked on Whistler Blackcomb for four-plus decades, currently as senior manager of mountain planning and environmental resource management, has been researching renewable energy for years. He's also enthusiastic, and, like Yadav, acknowledges that the investment must be viable.

"I will encourage any form of renewable energy that we can make the economics work. Absolutely!" he says. Another economic angle: He and the professor also recognize how these solar cells could be useful in lifting people out of poverty.

"[Solar power] is right there as one of the most impactful solutions to climate change, and what I really like—this is an important one for me—is how it can help people in poverty. Over 1 billion people don't have access to power grids," adds De Jong.

"Sunlight is the most accessible energy there is, and it costs so little to put up a small solar system."

The economics and small eco-footprint (a term coined by another innovative UBC team, Bill Rees and Mathis Wackernagel), along with the accessibility of sunlight are all behind Whistler Blackcomb's use of solar panels in about a dozen applications. Conventional solar panels power some gates where skiers are loaded onto lifts; control systems in WB's lift terminals; and weather stations that provide the daily weather data everyone using the mountains relies on.

SO WHY DON'T WE SEE MORE SOLAR AT WHISTLER?

Besides the ones used on Whistler Blackcomb, which are largely invisible to most of us, people think there are a lot of solar panels used in Whistler, and there are. Sort of. But first an explanation.

"Better tech is good for the climate crisis and global heating as long as it isn't a distraction [from] what is easily possible today. When this type of solar is commercialized, it will have greater importance in places where electricity is more fossil-fuel based and expensive compared to B.C. and Whistler."

Dan Wilson, planning and engagement, Whistler Centre for Sustainability

There are two types of solar panels with very different technologies: Solar thermal and solar photovoltaic, or PV for short. Solar thermal technology collects sunlight and transforms it into heat that's stored; it can be transformed into electricity, but it's usually used for heating water, like the 15 panels on Meadow Park Sports Centre in Whistler.

It's these thermal solar panels for heating hot water that people see the most on Whistler homes, largely in Rainbow subdivision where about 10 to 15 homes are using it. It's also a technology Bob Deeks, head of RDC Fine Homes and one of Whistler's most sustainable builders, describes as being "past its best-before date."

Photovoltaic solar panels use technology to capture sunlight and convert it into electricity. That's the type of application we're mostly concerned with in this article, not thermal; it's also the type of panel barely used in the Sea to Sky corridor.

Besides the dozen or so solar PV panels on WB and powering municipal parking kiosks, there are only three or four homes using them in Whistler along with one on Judd Road in Squamish. (Whistler doesn't track solar panel usage.)

An average residential solar PV power system is around 14 to 24 solar panels or about 4 to 6kW. The UBC team anticipates that their biogenic cells could be easily linked into such conventional solar panel systems to supplement them, not necessarily replace them.

"For us, the convenience is there but when we first engaged in this project, the business case didn't add up," says Richard Wyne, who loves that their B.C. Hydro bill for February and March was only $18. "We knew we were going to spend a bunch of extra money to do this, but Jen and I are both very happy with our decision to power our house with solar panels, and we'd absolutely do it again."

Through net metering, such as the Wynes have, people with solar systems only pay for the electricity they use, getting a rebate for any power they add to the grid.

"Net metering allows our residential and commercial customers to connect a small electricity-generating unit (up to 100 kilowatts) that uses clean or renewable resources to our distribution system," explained B.C. Hydro's Tanya Fish via email. "When customers generate more electricity than they need, they can sell the excess power back to us and get a bill credit towards their future electricity use. If they don't generate enough to meet their power needs, they buy power from us."

B.C. Hydro currently has about 1,850 net-metered customers, the majority of them on solar photovoltaic. Previously, more robust buy-back programs were available through net metering, but these were amended to ensure the size of a customer’s proposed generator is consistent with their needs when it became apparent some private operators were acting like unlicensed commercial power plants, selling up to $30,000 worth of power annually back to the grid.

Whistler's Official Community Plan, Community Energy and Climate Action Plan and net-zero ready building standard all encourage renewable energy like solar. But other than net metering, the only financial incentive in Whistler (and the rest of B.C.) for homeowners is a $250 rebate on an energy evaluation for your home.

So why don't we see more solar panels in use at Whistler?

Cost, says Rod Nadeau, managing partner of Innovation Building Group (IBG), which has 40-plus years at Whistler. Cost, the lack of incentives, financial or otherwise, and the fact that B.C. is 98 per cent powered by cheap, clean hydroelectricity all play a role.

"We have cheap hydro, and so the [return on investment] isn't there yet," says Nadeau. He explains that in a place like Germany or California, where you're paying 15 to 40 cents a kilowatt hour, solar panels make "tons of economic sense." In B.C., we pay eight to 12 cents a kilowatt hour and because of that, solar is not as economically viable.

To top it off, the municipality offers few incentives for builders.

"For all their talk, there is absolutely nothing," Nadeau adds. "There're no incentives, no expedited approval process, no bonus density, absolutely nothing, and there's not even recognition that you're doing it. But the reality is if you want something to be adopted, it needs to be cheaper, faster, better, easier, and if you don't hit all those buttons, why do it?"

Still, Nadeau and his partner are "doing it" because they believe in sustainability. IBG has built lots of energy-efficient properties, including a 45-unit rental building in Pemberton that's solar-ready for photovoltaic, which they intend to install next year, as well as a similar project in Golden, B.C.

"If you can have fewer solar panels to generate the same amount of electricity, it gives you more flexibility around design. Absolutely. Or on the flip side, it will allow you to generate more power from the same roof area if you want to be more self-sufficient. Anything that's more efficient is going to have a lot greater value and more interest."

Bob Deeks, head of RDC Fine Homes

Bob Deeks has a similar take. Whistler has the province-wide solar-ready requirement to encourage builders, and that's about it.

"Currently, with the cost of installing PV and what the comparative cost of electricity is, there is no pay-back model in B.C. Additionally, with most of the power consumed coming from hydro, you can argue that our power is green power."

But there is hope for more solar use wherever we live. Cost is dropping while efficiency is climbing—and that's without any new biogenic solar cells. Wyne points out they could install a solar system on their house today that would produce twice the power at half the cost.

Shannon Klassen has three more reasons. She's an independent solar-power advisor at Whistler and licensee with California-based Powur, a tech company trying to get as many homes as possible hooked into solar power."I have three kids and we watch the glaciers melt," she says. "It's really becoming more and more apparent that everybody needs to do as much as possible—it's an environmental crisis, right?"

To that end, Klassen will happily provide anyone with an accurate, non-invasive proposal for solar panels for your home or commercial building at no cost. With a little luck, and more development, that could include a biogenic solar system not too far in the future.

Solar in B.C. and beyond

Depending on the source and context, the global solar picture varies. But safe to say China tops the charts, with about one-third of world capacity, followed by the E.U., U.S. and Japan, not necessarily in that order. However, when it comes to photovoltaic solar watts generated per capita, Germany leads the pack followed by Japan and Italy. As for Canada, even though our solar capacity exploded from 16.7 megawatts in 2005 to 2,911 megawatts in 2017, we trail the rankings with only one per cent of world solar capacity.

Here in B.C., it's not that solar power is missing from the energy scene. More, it's not exactly big, largely because of cost (an average installation is usually cited in the $30,000 range) and the province's huge clean supply of hydroelectric power. Meanwhile, other jurisdictions shine.

In the U.S., the average cost of installing solar panels runs around $US17,000 but tax breaks and other incentives can drop that down around $US5,000 in some states.

Alberta, under its previous NDP government, invested $36 million to encourage solar and community energy projects under the federal government's Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. This includes an impressive rebate incentive of $10,000 or up to 35 per cent of the initial cost of installation. The goal: to have solar on 10,000 rooftops by 2020.

While no one knows what's going to happen under Alberta's new Conservative government, the investment is paying off. Right now, Ontario remains the heartland of solar capacity in Canada. For instance, the 100-MW Kingston and equally big Grand Renewable solar project near Hamilton—where Six Nations are the "landlord" and half a million solar panels gather the sun's energy—are the largest in Canada and among the largest in North America. But Alberta is Canada's new leading light in the solar department.

Energyhub.org ranks Alberta as tops in the nation in terms of the feasibility of installing solar power at home. According to CBC, about 250 solar companies are now operating in Alberta, with investments in solar projects totalling about $134 million. About 1,500 residential and commercial solar projects have been installed with another 900 on the way. The bulk, about 2,200, are residential projects, including my cousins' home on Pigeon Lake where they've just installed a full photovoltaic array.

As well, Alberta recently invested in three new solar facilities to supply the provincial government with 55 per cent of its annual electrical needs, effectively doubling the province's solar capacity.

Ontario's solar industry was thriving until premier Doug Ford nuked the solar rebate program. In 2016, the most recent year that figures are available, solar accounted for five per cent of the average residential electrical bill. But now many of Ontario's solar companies are looking to move to Alberta—at least they were, until Jason Kenney was elected.

With 25 per cent more sun than Ontario, our next-door-neighbour province is a likely solar hotbed—providing Albertans keep their eye on the renewable energy ball.