Sixteen Seconds

By Katherine Fawcett

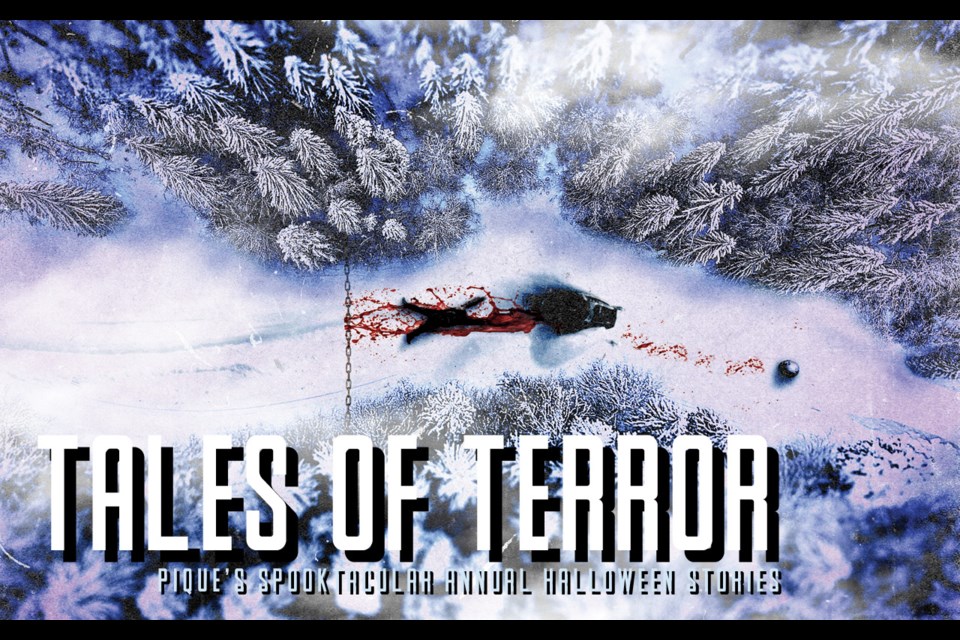

The human brain remains conscious for approximately sixteen seconds after decapitation. This is the second thing that runs through Hugh Hamilton’s helmeted head after it is severed from his cervical spine, spins gracefully through the air, bounces off the trunk of a tall Douglas fir and lands (right-side up!) with a gentle “whump,” in a cushion of fresh and fluffy snow about 10 metres from his flipped-over snowmobile.

The first thing that runs through Hugh Hamilton’s head is: That chain wasn’t there last winter!

In fact, it was.

But the last winter’s snowpack was a metre deeper, and the chain was buried, so Hugh and his friend Big Adam, who will arrive at the scene shortly, had actually snowmobiled right over it on their way to the glacier the year before.

Hugh had thought it was just an interesting piece of trivia, when he first read the thing about the sixteen seconds of consciousness two days earlier. He’d been in the Woodworking Room, supposedly grading three-legged stools, his shop students’ end-of-term project, but scrolling on his phone he was click-baited onto a page called “Thirty-Three Interesting Things You Didn’t Know About The Human Body.”

These thoughts he just experienced take a combined total of three seconds.

So now he’s down to thirteen.

The subtraction process, the sixteen minus three, although simple, takes him another full second. The old joke about the shop teacher being an idiot, an academic fool per se, only one notch up from the gym teacher really, has always bothered him. He resents the way the other teachers, in their short-sleeved plaid shirts and beige Dockers, look down on him just because he was hired as a “specialist” and doesn’t have all the same credentials they do. See if those English teachers and Calculus teachers know how to frame a house, he thinks. See if they can build a three-legged stool. See if they can maneuver a 220-kilogram snow machine along a decommissioned backcountry logging road.

Twelve.

His head is set quite comfortably in the snow. He imagines that a passerby, if there was any chance of one way out here in the middle of nowhere, might think the rest of Hugh was buried up to his neck right underneath. A fun mid-winter’s game.

His vision is still clear, and he can see the crumpled, lumpy, twisted one-piece snowmobile suit that holds his body. It lies face down—well, chest down—a few metres from the Ski-Doo, leaking black-cherry redness into the snow. A morbid stain on an otherwise pristine winter scene.

Eleven.

Well, at least he feels no pain. How could he? What’s to feel? And he knows that his body, way over there, feels no pain either. How can a body register sensation when there is no brain? It’s like a flashlight that’s had the batteries removed. Like an unplugged TV.

He wonders briefly about his soul. He’d kind of assumed it was located in the heart. Maybe not. Maybe it’s been here in his head all along. Or maybe it’s also leaking out of his body into the white powder along with the blood.

Ten.

There is no breeze. Like Hugh Hamilton’s decapitated body, the branches on trees on either side of the snowy trail are perfectly still. They slouch silently, uncomplaining, under their loads of white. Hugh wonders when he can expect his life to flash before his eyes. Isn’t there supposed to be some kind of brilliant white light he can’t look away from? A vision of an angel? His grandmother perhaps? Beckoning to him to just let go? To float towards the light?

But there’s no light. No angel. No granny.

There’s an $8,500 sled, his decapitated body, and the metal chain, still dripping with blood and some unidentifiable fibrous chunks, swinging in the cold; a silent, grave metronome counting the seconds like in a dream—some compressed into micro-moments, others stretched out forever.

Nine.

Almost half-way through his allotted moments. Time flies!

Maybe the reason there’s no angel, no grandmother, no brilliant white light is that grace and lightness isn’t what’s in store for him in the afterlife. Maybe he’s going somewhere … hotter. Maybe his sins have caught up with him and he’s going to pay for—

No!

He halts this ridiculous line of thinking. There’s no such thing as an afterlife. There’s this life, with its pains and pleasures, its guilty secrets and, if you’re lucky, a few flashes of joy. And when it’s done, there’s diddly-squat. Nada. Hugh figures life goes from a Grand Opening Celebration to a Going-Out-of-Business-Sale. Then there’s newsprint on your windows. End of story. So, you may as well do what you can to enjoy yourself before you lose your head. Live large, burn bright, and go out in a blaze of glory. That’s how he’s always lived.

Eight

Where’s Big Adam? Hugh thinks. He should be here by now. Good old Big Adam. A chemistry teacher, not as snooty as the rest, and always up for an adventure with him.

And, OK, let’s face it, the husband of his lover.

It’s cliche, he knows, the affair. Larissah is so beautiful. So fun to be around. They’d spent so much time together, the three of them. And when Big Adam dropped into one of his “moods,” when he and Larissah weren’t getting along, when Big Adam was up all night grading Chemistry exams, she turned to Hugh. It was inevitable and intoxicating, their little affair. They were so discreet, so careful. So playful.

Hugh guessed it put some spice back into Larissah and Big Adam’s marriage, this consensual fling. That’s what happens, right? And besides—monogamy is a cultural construction that ignores human nature and desire.

Or something like that.

It’s not like this head-being-lopped-off issue is some kind of punishment. There’s no way your actions on Earth—or, more specifically, in the bedroom—have anything to do with what happens after you die. Or how you die. Or when you die.

Do they?

Seven.

Time is messing with him now. And for once, he’s starting to wonder about the whole Larissah thing. About betraying Big Adam. Guy is his best friend, after all.

Am I an asshole?

Maybe he deserves to die like this. Maybe it’s karma.

He knows it’s too late to do anything about it, so he settles into the remaining seconds, and lets destiny take over.

It’s a relief, to be honest. The thought that the universe has a plan for Hugh, even now, in death, gives him a strange sense of peace. He knows he has seven wonky seconds left, and he feels a wave of an inner calm.

He has lived a good life. Made the most of every moment. He is not afraid. It’s nearly over. Everything is going to be OK. Everything is going to be fine.

Six.

Suddenly: the sound of a snowmobile. Hugh strains and sees his friend’s machine approach. Big Adam kills the engine. Runs past the bloody chain to Hugh’s twisted headless body. Cries out. Sees the helmet. Throws up.

Five.

Big Adam runs to Hugh’s head and lifts it up out of the snow. Blood drips. Hugh blinks. Big Adam shrieks. “My god, you’re still alive!”

Hugh thinks, shit, what if Big Adams drops me? He clenches his teeth and squinches his eyes just in case. But Big Adam holds tight.

“The cold snow must have frozen your neck’s stem.” Big Adam tucks the full helmet into the crook of his arm. He’s like a cephalophore, one of those saints who carries his own head around.

“Hang in there, man,” says Big Adam. “I think we can do this. I read somewhere you’ve got sixteen seconds.”

No no no no no no no no no no no no no no you don’t, thinks Hugh. Just put me down and let me—what’s the phrase?—rest in peace. He tries to speak these words, but the sounds are lost inside the helmet. Big Adam is crouching down at Hugh’s body. What does he think he’s doing? Hugh’s head is turned to the sky. Pale blue. And … A bright light! Oh! Yes! There’s that light everyone talks about! Hugh sighs in relief. Now he can just gently float like an angel towards the light, as they say.

Four.

Damn. Hugh realizes the light is just the sun.

Big Adam is lining things up. He places the wet stump of Hugh’s neck against the crimson mess of his body, still lying in the snow. He presses, presses, presses body and head together. Twists the head a bit this way, torques it that way. The focus on his face as he tries to save his best friend is so intense it nearly breaks Hugh’s nearly stopped heart.

“Yes. We need to make things right,” Big Adam says.

Hugh knows it’s futile. Big Adam is so painstakingly hopeful, it’s almost pathetic.

Three.

Who is Big Adam kidding? Make things right? How naive, to imagine he can just reattach a severed head and bring a three-seconds-from-death person back to life.

Big Adam, who can’t even see that his wife is having an affair.

Big Adam, who doesn’t know that his friend is a terrible person, and is on borrowed time anyhow.

Big Adam, who thinks he can put everything back together again.

Two.

But there’s something else in Big Adam’s face. Something terrible in his eyes. It’s not love, or fear, or grief. Hugh isn’t sure exactly what it is.

He considers a last-minute confession—a quick conscience-clearing—but there really isn’t time.

Big Adam presses and twists the body and the head just a little more, and there is a sudden click and a sucking sensation as the two parts of Hugh line up perfectly. His head is reattached. His body is made whole, again. Complete. Alive.

And Hugh is instantly plunged into a swirling, lava-filled pit of red-hot agony. Every ounce of pain that was withheld from him when his head was separated from his spine rages forth. It’s a scorching hot, jagged pain, like a sword that stabs and twists up into his skull, radiates through his brain, and pours down his spinal cord into every nerve of his body.

Hugh screams, but the sound stays inside his helmet, wraps around his face and squeezes tight. A nightmare grip.

Big Adam! Why? Why did you do this to me? Why did you bring me back to life?

But Big Adam is walking slowly back to his snowmobile. He’s swinging his arms like someone who has just completed something good. A job well done.

Hugh hears his friend start his snowmobile, rev the engine, and drive away.

One.

He strains his eyes but all he can see down the length of his body are the heels of his boots. The back pockets of his one piece Ski-Doo suit. The bloody chain, which is no longer swinging back and forth, no longer counting down the moments. And as the sound of Big Adam’s engine fades away, the once-decapitated Hugh Hamilton lies in the snow, both face down and face up, feeling the monstrous burden of hard truth.

Under the hunter's moon

By Kate Heskett

The old wooden bridge creaks and moans under her weight. Chrissie steps carefully, grateful for the light from the full moon. The Hunter’s Moon.

She should be at home in bed, finishing the readings for tomorrow’s class. Perhaps if she’s quick she’ll still have time. Chrissie hates being unprepared.

Her calf-high leather boots crunch determinedly through a thick layer of fall leaves, spindly shrubs grabbing at her legs. No one comes down here much any more. Not after what happened.

At least the rain has stopped. Chrissie walks beneath the face of an overhanging cliff. They used to hide here, on nights when it wasn’t safe to be at home. She and Tina would grab their packs, already loaded with sleeping bags, torches, marshmallows and a hunting knife, just in case. They’d hide in the back of the cave, telling stories until they fell asleep, Chrissie with her head in Tina’s lap. Tina was always the strong one. Only she could have seen past the creepiness of the cave, the unknown monsters that Chrissie was sure lurked there in the darkness.

But tonight Chrissie isn’t interested in the cave. She walks past the steep granite face and takes a sharp right turn towards the lake. I just have to get this done, she reasons, then I can concentrate on my readings.

It’s always this way. Every October she can feel the pull towards the lake, as if Tina is calling her back. It’s why she’s never moved; still living in her family home, in her childhood bedroom. It looks different now, of course. The bunk beds have been replaced with a queen-size, the walls painted a deep mauve. From the window, near the desk, she can look out to the trees at the back of the property. Sometimes she imagines she can see Tina emerging from the brush, dirty and wild, but unharmed.

A whiteboard and college schedule occupy the wall where she used to stick pictures from magazines. Chrissie always cut out the boys, the teen heart-throbs she hoped to meet one day. Tina preferred pictures of the stars. Not celebrity stars, actual stars. Pictures of galaxies and black holes and supernovas. Some of them were real, cut from science magazines and National Geographics. Others she’d drawn herself, from her memory of the places she went to in her dreams.

This year has seen a wet start to fall. Record rain has soaked the earth and the lakeshore is sodden, almost bog-like. Chrissie fights to stay upright as the hungry muck sucks at the soles of her shoes. It has always puzzled her, about the shoes. If Tina had walked down to the lake by herself, then why was there no mud on her shoes? The police said there were no other footprints leading to the lake, except for some large animal tracks, possibly a bear. But if it were a bear attack, they concluded, they would have expected to find … something. Something meant pieces. Bloody pieces. Instead, all they ever found was a pile of neatly folded clothes—the clothes Tina was last seen in, her favourite Nirvana T-shirt and torn black jeans—next to her mud-free Doc Martens. The clothes were found by a search party, days after Tina went missing, in a patch of purple asters by the lake.

Tonight, Chrissie stands among the same flowers, ten years after the disappearance. There must be something she’s missed. A clue or something that was only visible to Tina on that night. What was she doing down here? By herself? Why didn’t she wake me? They’re the same questions she’s been asking herself for years.

The moon is higher now, casting Chrissie’s long shadow across the lake. The water is still, a bottomless black pool, reflecting everything, revealing nothing. They never did find Tina’s body.

Chrissie begins to undress, just as she imagines Tina must have done, part of the ritual of trying to recreate her last moments. The October nights are cold. She couldn’t have been alive and naked for long.

She removes her shoes and socks and places them gently beside her on the wet flowers. Purple asters were always her favourite. She looks up at the moon, rocking slowly backwards and forwards, feeling her weight shift, from her heels to her toes and back again, the earth solid under her feet. She takes off her jeans, the fine hairs on her thighs bristling in the cold, carefully folds them, and lays them down next to her shoes. She pauses for a moment before removing her underwear. She feels exposed, like she’s being watched. But who else would be down here? Chrissie looks around, trying to locate the onlooker. There is no one else. Only her reflection in the lake.

A cloud passes in front of the moon, and her reflection fades away. She quickly removes the rest of her clothes, putting her shirt on top of the pile to discreetly cover her bra and underwear, just like Tina had done.

Except Tina wouldn’t have folded her clothes at all. Never one to suffer from shame or shyness, she was always first in the water, pulling off her clothes as she ran, discarding them where they fell. It was Chrissie who needed to wear a bathing suit, who habitually left her clothing piled neatly on the shore.

So why leave her clothes like that? Was it some kind of message?

The Hunter’s moon is the only time Chrissie is ever naked outside. Naked and looking for answers. The moon has completely disappeared behind the cloud. Was it supposed to rain tonight? Chrissie was hoping to see the stars. Never mind, she doesn’t need the light, she knows exactly where she’s going.

With no moonlight to guide her, Chrissie feels her way to the lake’s edge with her toes. The water is warmer than she expected. The sandy bottom soon gives way to sludge, but Chrissie keeps walking, slowly forward, until the water reaches her bare belly. In the pitch black she can’t even see her hands stretched out in front of her. She wonders for a moment if swimming is such a good idea. Maybe this time she could give it a miss?

Chrissie turns to go back to the shore, back the way she just came. She peers into the preternatural darkness, trying to make out the small beach. Wasn’t it just behind her? She turns and takes a step towards where the shallows should be, but finds only deeper water. She didn’t think she’d walked that far?

She pivots and takes another step. This time her foot sinks through the lake bottom, muck swilling up past her ankles, her presence disturbing the layers of decomposing leaves, and fish, and flesh …

She takes several deep breaths, tries to calm her rapid heart. She knows she is close to the edge of the lake. She knows she can swim if she has to. It’s just a lake, Tina’s voice in her head, It can’t hurt you. A memory of Tina’s voice. Or is it? Why does it sound like she’s standing right here?

Chrissie takes one more deep breath and tries again to leave the water. She slowly lowers her foot. This time there is no bottom. Just a sucking grip dragging her down.

Kate Heskett is an award-winning poet and writer living in Whistler. They can often be found at Whistler’s lakes, trying not to get stuck in the muck.