Lil’wat Chief Dean Nelson stands on the edge of the First Nation’s four-hectare community farm, on a warm Friday morning in early July.

A group of four Lil’wat youth work diligently in the field before us as Nelson looks on.

“They’re pretty happy here, because it’s a very good environment,” Nelson says, watching them work.

“They’re all really connected to it, and invested in it, and that makes a big difference.”

The farm has come a long way in three short years, he says, and now supplies produce boxes to the community for purchase each Friday.

With a further 400 hectares of farmland that could potentially be added to the plot, Nelson sees a lot of potential.

“We have all that land back there that’s sitting there … People talk about cannabis, and hemp and that kind of stuff. That’s very doable now.”

The farm represents just one area of untapped potential for the Lil’wat.

Though the First Nation has been working on economic and community projects of different sorts through its Lil’wat Business Group for years, the adoption of Whistler’s updated Official Community Plan (OCP) represents a new era for the Nation.

But the farm represents something else, too.

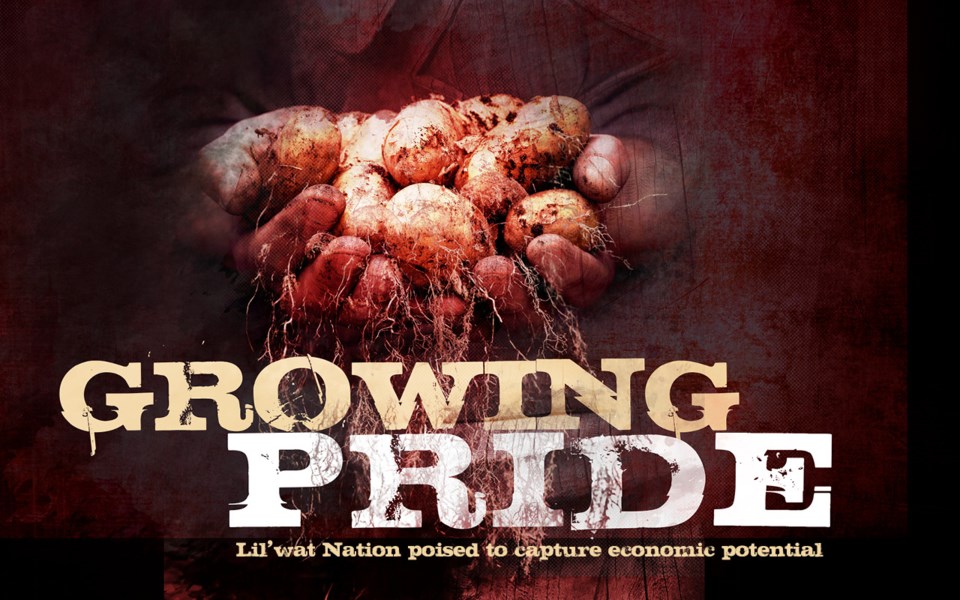

Nelson says he will often take photos of its crops to share with the community, and marvels at how something so simple as a sack of potatoes can create so much pride.

“That sack of potatoes, it’s just a sack of potatoes, but it’s just where it comes from, and how it’s packaged. It’s just amazing,” Nelson says.

“We are growing emotion, you know? The emotion of pride.”

‘Sky’s the limit?’

Lil’wat Business Group CEO Kerry Mehaffey has worked for the Lil’wat Nation for more than 12 years, serving previously as manager of on-reserve lands and as economic development officer.

A lot has changed for the Nation in that time.

“I think there’s substantially more economic opportunity now than there was then,” Mehaffey says during a walking tour of Mount Currie with Nelson.

“I think that there was a lot of really good work that was done before I started here in terms of negotiating for assets—like a lot of the land base around Whistler and in Pemberton—and so now it’s sort of been more focused on implementing some of those projects.”

With the adoption of the Resort Municipality of Whistler’s OCP (and a related Framework Agreement signed between it, the local Squamish and Lil’wat Nations and Whistler Blackcomb), the Lil’wat have a lot of work ahead of them.

The Framework Agreement details the Emerald/Kadenwood land exchange, the formation of an Economic Development Committee and the potential development of Whistler Blackcomb Option Sites in partnership with the Nations—all of which were first mentioned in a Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2017.

The Kadenwood project holds the most potential in the short-term, Mehaffey says, while the option sites represent a longer-term opportunity for all parties.

The Nation also has a 50-50 agreement with a development partner to develop the next six phases of the Pemberton Benchlands, which could yield a 300- to 400-unit subdivision over the next 20 to 40 years.

Then there’s the Nation’s long-awaited Function Junction gas station development in Whistler, which has met with some delays due to the complicated nature of traffic management at the busy intersection.

“For me on the business side, I’d say it’s probably the highest priority development project that we have,” Mehaffey says, adding that the Nation is still aiming to break ground this fall.

“There’s still some work to do. Hoping to do it this fall means probably next spring, but I’m always optimistic,” Mehaffey says with a laugh.

On the Kadenwood lands—about nine hectares adjacent the existing Whistler neighbourhood—the RMOW will support a new site-specific zone for a mix of low- and medium-density detached duplex and townhouse dwellings (that may also be used for tourist accommodation), with auxiliary residential dwelling units for employee housing as laid out in the OCP.

The lands will be developed in partnership by the Lil’wat and Squamish Nations, and the land supports a development of between 40 and 60 units.

It’s too early to say how the Nations will approach development, but the important thing is to remain flexible, Mehaffey says.

“The big thing for me is to have the option, to not say, ‘Hey, we’re pigeonholed, we have to bring in a partner because we can’t do it,’” he says.

But, given the fact that the Lil’wat Nation technically operates a local government, it might make sense to bring in a partner.

“Real estate is a high-risk, high-reward game; we don’t want to be risking $3 million that could go towards running programs in the community or building 20 houses or doing all these other good things,” Mehaffey says.

“So there’s definitely a balance there.”

Taken together, the various projects represent massive potential for the Lil’wat, but it’s hard to quantify exactly how much.

Asked about the cumulative economic potential unlocked with the new OCP, Mehaffey looks to Nelson.

“Dean? Sky’s the limit?” he says.

Nelson considers the question for a second.

“Pretty much,” he says.

An enhanced presence

As much as Whistler’s updated OCP is about economic opportunity, it’s also a framework for reconciliation between local First Nations and the RMOW.

It was just over six years ago that Whistler’s updated OCP was quashed by the Supreme Court of B.C. after it was determined the provincial government did not properly consult with the local Squamish and Lil’wat Nations.

But even with literal centuries of presence on the land, some still raise questions about archeological studies, and the legitimacy of First Nations land claims in Whistler.

Those questions show the need for more education, said Squamish Nation Councillor and spokesperson Chris Lewis, in a July interview with Pique.

“Our stories, cosmology and archaeological record go back thousands of years in terms of both Nations being in the valley, being within the area. We have stories of kinship between us and Lil’wat, that tells us of our presence within the corridor, what we utilized the areas for and all of those types of things,” Lewis said.

“There needs to be further opportunities for the Nations to showcase our visibility, showcase our connection to the area, to the mountains, to the valleys and to the lakes, because our history as Squamish and Lil’wat is Whistler’s history as well.

“It’s a vast array of knowledge and connections … I think a lot of people would be interested in terms of how Squamish and Lil’wat, as the original inhabitants of this area, utilized it, and how we were connected to it, prior to it becoming a world-class resort.”

In Nelson’s view, teaching the history and complexities of the Indian Act and reservation system would also help create a broader understanding between the communities.

Some people don’t understand, Nelson says; sometimes all they see is First Nations people getting things for “free.”

“There’s nothing free. I paid with my heart and my soul, growing up here, with all the stuff that happened to our people,” Nelson says.

“The trauma is still here. It’s passed on. If you don’t stop it, then you pass it on to your children whether you know it or not.”

‘The pride is there’

As our tour carries on, Nelson greets community members by name as he walks steadily down the centre of the highway.

We stop outside the Lil’wat Gas Station at the turnoff to Lillooet Lake Road, and Nelson greets a high-school-aged student arriving for work—one of five the Nation hired for the summer.

A former schoolteacher, Nelson says he has stayed connected to the community’s youth since first being elected chief in 2015.

There were some opportunities for Nelson as a young man, “but I always believed that they were just programs,” he says.

“They were going to start, they were going to end, and nothing else would come from them. That was my mindset growing up.”

Investing in the community allows the Nation more agency over its future, Nelson says.

Like the sack of potatoes, he sees the gas station as a symbol of something more.

“We’re promoting emotional attachment, and pride—this is yours. All of this is your guys’ stuff. It’s not mine,” he says, gesturing to the gas station and the community beyond.

“Those kids are going to grow up knowing that this is there, and this is theirs.”

With about 1,700 members, the Lil’wat Nation is the fourth largest on-reserve community in B.C. (out of 203 bands).

While capitalizing on economic opportunities is important, Nelson knows there are multiple pieces to the puzzle.

“This stuff is good, but we still have the other side of it, the social side of it, that we have to work on,” he says.

“This stuff helps. Every day you walk by and you’re reminded that, OK, things are getting better.”

Nelson recalls going to McConkey’s ski school in Whistler as a kid, and the pride he felt seeing Lil’wat Nation members working as construction supervisors at the Conference Centre.

“It was amazing, because I knew those guys. I was like ‘Hey! You guys are the bosses here?’ [And they said] ‘Yeah, pretty much,’” he says, adding that it’s an anecdote he once shared with the grandchildren of those workers, now in the construction field themselves.

“The pride is there,” he says.

Ensuring that pride carries on to future generations will require further investment in the community and engagement with its people, Nelson says.

And as for the youth, “they’re happy,” he says.

“Hopefully we get used to good things.”