The Creator wasn’t happy.

He had blessed the Skwxwú7mesh with an abundance of natural resources and beauty, and yet they were forgetting the teachings of their medicine people and spiritual leaders.

Despite repeated warnings, the people now known as Squamish Nation continued to disrespect the land and each other.

And so the Great Flood came.

Seeking escape, the Skwxwú7mesh loaded their families and supplies into canoes. Many perished as the land beneath them was swallowed up by water. Those who survived were able to tie their canoes to the top of Nch’kay’, the tallest mountain in their territory, until the waters receded. Chastened, the Skwxwú7mesh returned to their settlements with a newfound commitment to follow the Creator’s ways. They would be wise stewards of the land.

Fast-forward thousands of years, to 1860. The British Navy sent a survey team to the coast that, seven decades earlier, Captain George Vancouver had meticulously mapped out. The captain of the survey ship was George Henry Richards. As he sailed up the Howe Sound, he couldn’t help but be impressed by the snow-capped volcanic peak of the highest mountain in the Coastal Mountain range.

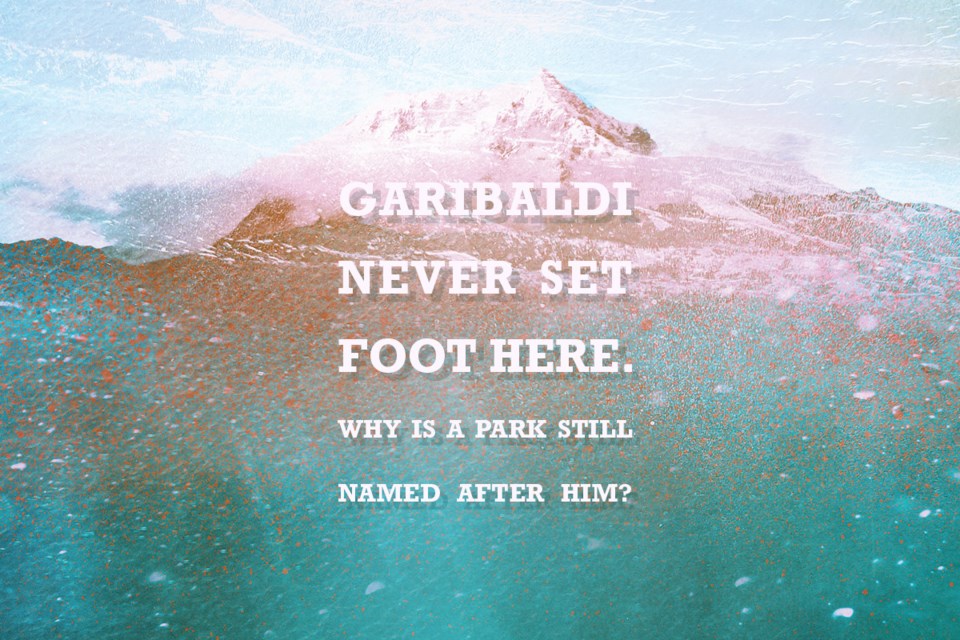

For reasons lost in the mists of time, Cpt. Richards was also deeply impressed by the recent exploits of an Italian “freedom fighter” named Giuseppe Garibaldi. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, Garibaldi was “a republican who, through his conquest of Sicily and Naples with his guerrilla Redshirts, contributed to the achievement of Italian unification under the royal House of Savoy.”

Firing his ship’s guns, Cpt. Richards christened the mountain in honour of a man who had never done anything even remotely connected to this land.

In another leap of time, it’s the early 1900s.

The mountain and its bountiful valleys had long been popular with trappers and prospectors. Mountaineers saw it as their Mount Everest. The first recorded ascent was achieved in 1907 by a group of six men who were instrumental in founding the British Columbia Mountaineering Club that same year.

Adventurous souls built a few rudimentary cabins and organized summer camps.

“In 1913, W. Gray and P. Long went in ahead of the camp to blaze a trail for pack horses,” writes Kate Bell in her detailed 1984 paper called the Cultural History Themes of Garibaldi Provincial Park, Black Tusk and Diamond Head. “Now that access into the meadows [above Stony Creek, at elevation of more than 900 metres] was much improved with a pack horse route, the climbers sought ways to cross Garibaldi Lake, although boating did not originally start out as recreational pursuit but rather a fast and convenient means of getting to Sentinel Bay.”

The Alpine Club of Canada soon added its voice to calls to protect such “great natural beauty” for the growing populations of Vancouver and Victoria.

In 1917, it wrote to Premier H.C. Brewster: “Areas such as this, where the beauties of British Columbia mountain scenery are so exceptionally well displayed, when made easily accessible and properly advertised, become a useful asset and draw many visitors from various parts of the world, thereby providing considerable revenue through the monies spent visiting them.”

Besides, the letter adds, “it may be said that, owing to its high altitude and mountainous character, it is not likely that there are at present outside individual interests that would be affected by the creation of such a scenic reserve.”

The province created the Garibaldi Park Reserve in April 1920. Seven years later, it enhanced the status to the 195,000-hectare provincial park that, as the Alpine Club predicted, attracts thousands of outdoor enthusiasts and Instagram adventure seekers to one of the most photographed places in British Columbia.

Today, on the 100th anniversary of the park reserve’s creation, a pandemic has tossed life upside down for people around the world. It’s coinciding with a time of cultural upheaval. The Black Lives Matter and Idle No More movements have sparked soulful conversations about the need for a more inclusive retelling of our national narratives.

So, is it time to change the name of Mt. Garibaldi to the culturally and historically more appropriate Nch’kay’?

When you restore Indigenous names, it creates an opportunity for the Squamish people to start telling their stories, says Chris Lewis (Syeta’xtn), a councillor and spokesperson for Squamish Nation.

Noting how road signs along the Sea to Sky corridor now include Indigenous names, he says that by exposing people to how the land was first called, you prompt people to start asking questions. Those questions lead to deeper understandings of First Nations peoples both past and present.

“Everything we do as Skwxwú7mesh is based in place,” Lewis says. “Our ancestral names come from a place, our songs, our spiritual aspects. They tell people what has occurred here or what the place was used for.”

When those names become more broadly used, “our history becomes everyone’s history.”

Nch’kay’ mountain gets its name from the river that flows along it. At first blush, its meaning seems incongruous for a mountain of such significance: dirty place or grimy place.

Dirty?

“If you go to the main streams that flow off of the mountain, they are just choked with volcanic debris—fine mud,” explains retired geologist Bob Turner. “You can’t drink that water and it’s because the volcanic rock that makes up the mountain [is] weak and unstable.

“Even in the summer when the winds blow, you can get those dust storms that pick up the volcanic dust from the upper mountain slopes. The name Nch’kay’ is just so appropriate.”

That volcanic rock was also a main source of trade for the Squamish people. Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass found where molten materials flowed down like a river from the peak. When fractured, obsidian has hard, sharp edges that can be turned into coveted tools.

“When you have a resource like that it creates wealth and knowledge,” Lewis says of obsidian’s early value. “Through new archeological technology that finds the DNA of the obsidian artifacts, we can trace obsidian from Nch’kay’ far into the Interior of British Columbia and all down the coast to Portland.”

Nch’kay’ also looms large in Squamish culture as a place of spiritual training. “Our people would go up into the alpine and sub-alpine terrain and isolate themselves as they tried to figure out who they would want to become,” he says.

Lewis notes that in a modern-day context, the Squamish Nation’s economic development corporation is called Nch’kay’. “It represents the highest mountain in our homelands so that we strive for that greatness and specialness. But it also reminds us that, dating back to the story of the Great Flood, that we always have to stick to our cultural ways and our teachings because when we stray from that, that’s when bad things happen.

“It reminds us of our connection to the natural and spiritual world and how we should conduct ourselves as Skwxwú7mesh people in everyday life and on the land.”

While the Squamish Nation has not made a formal request to the province to change the name, Lewis says they appreciate that there’s now a growing social and political licence to restart the conversation.

David Karn is a spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Environment. “BC Parks,” he writes, “has a Collaborative Management Agreement with Squamish Nation. We work together on many initiatives in parks and protected areas within the traditional territory of Squamish Nation. We have discussed name-changing initiatives with Squamish Nation and hope to work with them in the near future on such initiatives.”

Just as nearly every culture has its great flood story, Lewis believes there’s value in having the name Nch’kay’ serve as a cautionary tale for everyone: beware of treating the natural world unwisely.

“Our story of Nch’kay’ is about losing our way,” he says. “We weren’t listening to our elders and our teachings. As a result, the Creator brought the waters as a reminder of the gifts that were given to us by the Creator.”

The geological telling of the Squamish Nation’s Great Flood

High atop Canada’s Western mountain ranges, geologists have been amazed to chance upon the fossils of prehistoric aquatic creatures.

How did remnants of a vast tropical seabed wind up touching the sky?

“The reason there are fossil shells on mountain tops is not because the water was that high,” says retired geologist Turner. “Mountains get pushed up and when they get pushed up they carry with them all the geological materials that are part of the colliding zones.”

One-hundred million years ago, this part of the world was covered by a vast sea. “We’re talking about extraordinarily ancient events,” Turner says. Volcanic activity near Squamish began 2 million years ago and the most recent eruption on Mt. Garibaldi, the highest volcanic peak in British Columbia, was about 14,000 years ago.

For the people of Squamish Nation, Mt. Garibaldi looms large—albeit with a different name. When the Great Flood covered these lands, the Skwxwú7mesh got into their canoes to escape the rising waters. They tethered their canoes to the top of the mountain until it was safe to return.

From a scientific perspective, Turner says, “it’s not surprising that floods would figure large in Squamish Nation history because they’re a riverbank people. These rivers would be very prone to floods.”

Even in the short European settlement history of this area, floods have had an impact. Turner recalls seeing a photo in the Squamish town library that shows downtown Cleveland Street entirely under water in 1940. Dikes were built to withstand what’s known as a 200-year flood—a flood that might occur once every 200 years—but that doesn’t preclude there being a 500- or 1,000-year flood.

The story of the Great Flood’s rising waters also makes sense weather-wise. While the Cascadia earthquake of Jan. 26, 1700 created a tsunami that submerged the west coast of Vancouver Island, the island’s land mass prevented the tsunami from reaching Vancouver’s North Shore.

“The Squamish story completely fits into what we know about floods, in that they’re largely rainfall driven. Sustained rains can make giant floods,” Turner says.

“In my mind, it’s just a question of how high the waters really rose. Everything else fits in and it makes sense that they would get into their canoes to ride out the floodwaters. It strikes me as a very authentic story.”

What’s not authentic is naming the mountain after an Italian “freedom fighter” from the 1800s.

“It’s just such classic arrogance to slap on the name of someone who didn’t even visit the place, especially since it’s such a prominent feature on the coast,” Turner says of a British ship captain’s decision to name the mountain after Giuseppe Garibaldi on early survey maps. “It would be a real gift to all of us to rename it Nch’kay’.”

Martha Perkins is the North Shore News’ Indigenous and civic affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.