Throughout its history, the Pemberton region has experienced numerous waves of settlement—from gold seekers travelling through to the Cariboo gold rush in the 1880s to a wave of speculators and homesteaders that followed the railway in the 1910s.

Hundreds of settlers have come to the Pemberton Valley with each successive wave and built lives for themselves. Many of those early pioneer families’ names have been engraved as landmarks you’ve heard the names of but may not know the stories behind, from Poole and Miller Creeks to the iconic Mount Currie that watches over the valley below.

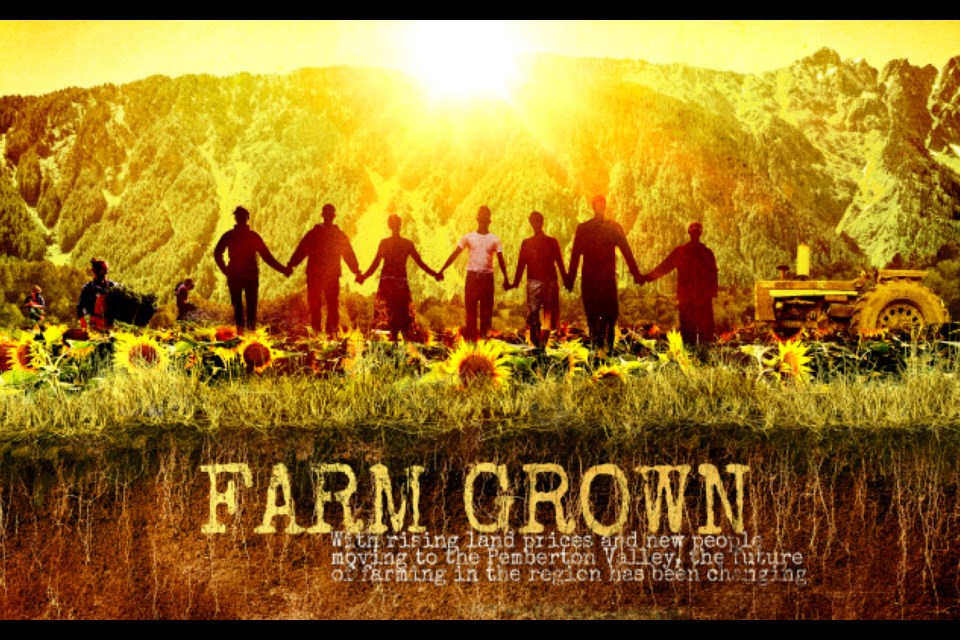

Over the last 100 years, farming has changed considerably across the region. Farms have varied from small sustenance operations serving hungry adventurers on their way to the gold-laden mountains north of Pemberton to modern times, diversifying their operations so events and agri-tourism are part and parcel of the keys to success.

The region continues to change as the next generation begins to take the reins on the ever-shifting future of agriculture in the Sea to Sky.

Early agriculture

The year was 1851 and a young Scottish lad, just 17 years of age, named John Currie, sought adventure and riches. After hearing tales of the gold-bearing lands in the expansive western half of the continent, he made his way to California and British Columbia for the gold rushes that brought risk-takers from around the world.

Currie didn’t see much success as far as gold finds in California went, and figured to try his luck in the Cariboo, which was experiencing one of the largest rushes in the world at the time.

On his way through the breathtaking region along the Lillooet Trail, Currie fell in love with the Sea to Sky long before the tourist-attracting moniker applied to the area.

In 1888, Currie and Dugland McDonald, who he met in the Cariboo, partnered together and applied to survey District Lots 164 and 165 in the Pemberton Valley. The two lots were where the modern Village of Pemberton lies today—at the foot of the impressive mountain that bears Currie’s name.

Currie later married a St’at’imc/Shuswap woman named Seraphine Tlekenak from the Fountain area near Lillooet, and bore three children together in Pemberton, with many in the Lil’wat Nation still tracing their lineage back to the couple, considered the community’s first permanent settlers. Seraphine later remarried and lived to be more than 100 years old.

Not long after Currie set up the first farm in the region, another adventurous Scot would find his way to the area after trying his luck in the cold, Arctic gold rushes of the time.

William Morgan “Jock” Miller, much like Currie, was a Scot who sought adventure at a young age. Miller joined the military at 16 and served everywhere from Africa to Sri Lanka to Hong Kong before eventually ending up working as a seaman in the burgeoning province of British Columbia.

Miller’s adventures would eventually lead to the gold rushes in northern B.C. and the Yukon at the time, and he would make his way to Dawson City, which was booming with life from the Klondike rush, and try his luck at mining—with mixed success.

After a few years, he eventually would make his way to Pemberton and, with his brother Bob, would acquire land in the middle of the valley in 1895, near a creek that still bears the family’s name.

The Millers came as pioneers to farm in the valley and have continued the tradition for four generations. Their farm is an example of how agriculture has changed—and continues to change—in the region.

Five years ago, the Millers created a farm-to-bottle craft brewery called The Beer Farmers, one of the only farm breweries in B.C. that grows its own barley right on the property.

The Millers took a risk, much like previous generations had, and it has paid off. The Beer Farmers have become a hallmark of sustainable farming in the valley and reflect the potential for agricultural-focused tourism in the region.

The brewery has become a favourite spot for locals and tourists at events such as Slow Food Cycle, taking place this year on Aug. 21. A fun-filled cycling tour of Pemberton’s farms, the brewery has become one of the event’s main attractions.

“Farming in the region has definitely changed. We are lucky because people want to see a farm, and we’re a working farm. We’ve got 30 acres of barley, and we’ve got organic seed potatoes that we’re growing, and then we rent out a bunch of acres to someone making hay here,” says Bruce Miller, who took over the farm in the early ’90s after his father, Donald, passed away.

“All our land is getting farmed, and we’re growing barley for the brewery. So that’s all part of a whole new concept, and we’ve ended up getting a lot of retail sales, so we don’t have to go through a wholesaler in Vancouver.”

In addition to renting out part of their land for haying, the Millers also lease 10 acres to Laughing Crow Organics, which has crafted their own success story in the valley.

Laughing Crow is one of a dozen organic farms that have popped up over the last decade in the region and feature prominently on the Pemberton Farm Tour, a self-guided tour designed to promote agritourism in the valley.

According to the Pemberton and District Chamber of Commerce, there were 125 farming operations in the Pemberton region as of 2021, producing gross farm receipts of $6,526,365.

A changing region

Due to its proximity to Whistler, low interest rates, ample job opportunities, and ease of access to major markets like Vancouver, land prices have surged in the Pemberton region in the last few decades.

This follows a wider national trend, as many agricultural regions face pressure from encroaching urban areas. According to Statistics Canada, “the reported total market value of land and buildings for farms in Canada increased by 22.7 per cent (in constant 2021 dollars) from the previous census, totalling $603.8 billion in 2021.”

The surging land cost has made it difficult for young farmers to get into the market, with many new farmers often resorting to leasing from existing landowners.

Frank Ingham, a Pemberton realtor and farm owner, has lived in the valley for decades and has seen the town’s demographics transform in that time as more people move to the valley from Whistler and beyond.

“In the last six years, we’ve noticed quite an influx of people—certainly from COVID—a very noticeable amount of folks coming from Whistler. In the past, that didn’t happen, but some full-time residents want a little more space, they want the garden area,” he says.

The realities of the real estate market in Whistler have also made it easier for sellers to fund a relocation to the Pemberton Valley.

“A little chalet in Emerald or Alpine Meadows was worth $500,000. Now it’s worth $3 million or $4 million, so you can cash in and get on to half an acre or more and have some money leftover in the bank,” Ingham says.

The COVID trend hasn’t been limited to Whistlerites either, as Ingham has seen people coming from the Lower Mainland and around the world to settle in Pemberton.

“The buyers are coming from all over the globe, and again, we have to keep it in context. Pemberton is not very big as far as the number of sales,” he says. “In recent years, I sold farmland to folks from South Africa; a young couple in their 40s; Americans; sold property to a family who was originally Canadian and lived in Dubai; and an Iranian gentleman who bought a couple of years ago as well.”

While Whistler commonly gets prospective international buyers into the door, it’s not unusual for clientele to become enamoured with the green space, privacy and mountain landscape that Pemberton provides.

The clientele can also range depending on the type of property. For example, smaller five- to 10-acre lots tend to be more attractive to younger retirees and families. In contrast, farms in the 50-to-100-acre range have caught the eye of large companies in the Lower Mainland.

“I’ve had many larger farmers come up from the Fraser Valley to get a sense, with land at a quarter of the cost,” Ingham says. “I suspect over time we will see more production types of people coming to our little valley, like it or not. So that is something to look at down the road.”

Passing the torch

Even amidst the growing challenges of running a farm in 2022, one couple is still trying to keep the farming tradition alive in their family.

Riley Peterson and Olivia Kester run Blackwater Creek Orchard, a small, four-acre mixed fruit and vegetable farm located in the Cayoosh Range, north of Pemberton.

In 1977, Peterson’s grandparents, Audrey and Warner Oberson, acquired the acreage as a retirement homestead and planted dozens of fruit trees, along with a large garden.

As the years went by, the Obersons would eventually get to a point where homestead farming became too much, and they planned to move to Pemberton, raising the question of precisely what to do with the property. Luckily for them, their grandson, Riley Peterson, was passionate about farming—and keeping the tradition alive.

“Every summer, I’d come up here and help them pick cherries and do some of the farming my whole life. This property was kind of always in the back of my mind: what happens when they get too old for farming and want to move to somewhere a little closer to some services?” Peterson says.

“It just so happened that the year I graduated from university, which was 2016, they ended up moving down to Pemberton, and so the property was open, and I took the chance and agreed to move up there.”

With virtually no experience, Peterson did a season at Plenty Wild Farms in Pemberton.

“I learned the ropes in that first year, then the second year moved to part-time and met Olivia at the Pemberton Legion. We ended up hanging out more and talking about farming, and then she moved up here with me in 2017,” Peterson notes.

Riley and Olivia were relatively young when they got into the farming business, at least by average farming standards, at 25 and 27, respectively. According to the chamber, the average age of Pemberton farm operators is 51.

Over the last four years of operating, the couple has worked to modernize the orchard, replacing the older, larger trees requiring 12-foot picking ladders with a modern trellis system.

Currently, Riley and Olivia maintain the orchard as their primary source of employment for the summer and then work part-time jobs in the winter. Their long-term dream is to take winters off so they can go travelling.

The couple has begun thinking about creating value-added products like fruit leather, cherry raisins and apple chips from the leftover fruit that doesn’t make it to the farmers’ market to diversify the business.

“We have so much extra fruit at the end of the season that is just unsellable or blemished. We process a lot for ourselves, but we think this would be perfect for the winter markets to extend the season,” says Peterson.

In addition, the couple has been brainstorming different ways to increase their income from agri-tourism.

“We were thinking about maybe doing long-table dinners or having some yurts on the property to draw people in,” Peterson says.

“It feels like farming has almost become not just farming now. It’s a lot of marketing; many farms have a great social media presence, and it ends up paying off if you get people to engage with the brand and your farm.”

Peterson notes that going into farming at such a young age wasn’t an easy decision, but he doesn’t regret it.

“It was a pretty hard decision, but I felt like if I didn’t do it, then the chance would slip by me, and I don’t know if I would have been able to afford land elsewhere if they ended up selling this place. I know there are some big barriers to young farmers getting into farming, especially in this region where the land prices have gone crazy,” he says.

“It was kind of a hard decision in the sense that a lot of my friends were trying out new things and going travelling, and I was deciding to put down roots and not go anywhere, and I think that affects a lot of people’s decision to kind of settle down and farm.”

Another couple of young farmers carving a path for the future of farming in the region are Sophie Campbell and her business partner, Rachel Spruston. This year, they launched a new flower farming business called Iris and Bear Flowers.

Both are 27 and have been able to get their start as farm business owners thanks to assistance from others in the Pemberton Meadows.

“We honestly have a pretty unique situation. We don’t lease land. I live out in the Meadows on a property with a few different dwellings and lots of fields,” says Campbell.

“My landlord has given us space on her land to grow, which is great to have somebody so supportive of that because I think if we had to lease land, we couldn’t afford to do it.”

Campbell came to the Pemberton Valley after finishing university, where she studied agricultural business and worked at various farms in the United States.

When she first came to the valley, she worked for Rootdown Organic Farm with Spruston, where they learned about farming in the region and got connected to the local farming community.

“We’ve gotten so much help from the farming community. Through the spring, we were able to borrow some greenhouse space, and basically all of our equipment has been borrowed or rented from other farmers,” Campbell says.

“We’ve received a ton of advice and help from folks at Laughing Crow Organics and Ice Cap Organics, and obviously, what we learned at Rootdown helped us.”

Starting a new business has been complex and fraught with challenges, as the pair has continued working full-time jobs on top of starting the new farm operation.

“In terms of starting a farm, it’s super complicated. It requires a lot of troubleshooting. We ran into hiccups with our greenhouse. Heating the greenhouse, we are doing it with a small propane heater. With such a cold spring, it wasn’t enough, causing the plants to be stunted,” Campbell says.

“We were also turning new ground in our field this spring, so we’re just battling a weed problem, pretty intensely. Some financial constraints have made it difficult, but I also feel we’re lucky to be supported by the farming community here and feel like we are being pushed forward by them, which is really awesome.”

On top of the logistical challenges and time constraints, the couple has also had to develop a marketing strategy for their flowers which Campbell noted can be complicated.

“Finding a local market that can buy all of our products has been a challenge, but I think we’re slowly figuring that out. That seems like the [kind of challenge you encounter in your] first year of doing a project like this, something you fumble through because you’ve got to figure out what your niche is,” she says.

Campbell believes it’s the sense of community that has kept nascent farmers working towards their longheld goals in the valley.

“There’s quite a community of young farmers in the Pemberton Meadows, and most are working for other people right now. All the organic veggie farms in the Meadows hire like four or five farmhands every year, and we kind of all get to know each other, which is cool,” she says.

“It’s nice to be surrounded by this younger agricultural community, and every now and then, one of them will get something started, whether here or on the island where it’s a little more affordable.”