It is a balmy day in August 1987, all the excuse Dave Williamson and Rod MacLeod need to get out of the office for a while and escape the oppressive heat. Working as planners for what was then the Whistler Mountain Ski Corporation, Williamson and MacLeod are surveying a potential lift line near mid-station, hanging flags and doing some fall-line analysis as they walk through the lush, moss-laden understory of an old hemlock forest.

As they venture downslope, making idle chatter, Williamson spots something in the distance: a gleam of white peeking up from out of the verdant landscape.

"Hey, look, there's a skull," he says to his supervisor, half-jokingly.

"No way, it can't be," MacLeod replies.

They continue on to get a closer look when, some 15 metres away, a realization dawns on Williamson: That really is a skull.

The pair then runs through the most likely scenarios, as we tend to do when confronted with such an improbable reality. It's a rock, MacLeod suggests. Or a bear skull.

"'Well, if it's a bear, it's been to the dentist, because I can see its fillings," says Williamson, now peering intently into the skull's jaw, which sits in vivid contrast to the evergreen bed of moss beneath it.

"This thing has got a bullet hole in the side of it," he observes.

"No, no, that's an ear hole," retorts a still-skeptical MacLeod.

"Well, it has got two ears on the side of its head then," says Williamson, the last shred of doubt evaporating in his mind.

"Holy moly, we just found something here."

Mystery grips a sleepy ski town

The Whistler of 33 years ago was of course a very different place than the hypermodern ski mecca it is today. With a mid-'80s population hovering around 3,000, it would have been almost impossible for a local to go missing without someone noticing.

In fact, even unsolved missing persons cases were relatively rare back then, and Sandy Boyd, who was VP of operations for Whistler Mountain Ski Corporation at the time, told the Whistler Question in an article soon after the skeleton was found that there had never been a lost person reported on-mountain that the lift company was unable to track down.

While there is no mystery surrounding the ultimate cause of death—a post-mortem confirmed the John Doe died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound believed to be a deliberate suicide—the few additional facts investigators managed to turn up have only added to the puzzle of the man's life.

First, the basics: We know the heavily decomposed remains had been there for at least two years, possibly three, and belonged to a Caucasian male between 30 and 49 years of age. He was estimated to be approximately 5-9 in height, weighing 151 pounds, with long brown hair and was wearing a white Daniel Hechter shirt, white Nike court shoes, and a powder-blue K-Way jacket when he was found.

An examination of the skull indicated the man had poor dental hygiene, and based on the dental work he had undergone, police surmised he had probably visited a North American dentist. The gun recovered near the body—a .38 calibre revolver dating back to the First World War—was later traced to a 1983 theft in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Curiously, the man was also found with a single South African Rand bill in his pocket, adding more questions as to his possible origins.

With no vehicle found nearby, it's likely the man made the roughly two-hour walk uphill from the village—not uncommon in those days—before settling on the serene backdrop of where Franz's Run now sits to end his life.

"We were working but there wasn't a lot of activity on the mountain at that time," says Williamson, who is now the principal for environmental consulting firm Cascade Environmental. "It was before the bike park. There were no operations in the summer. I think he just hit the end of the road, basically, where the Pony Trail bypasses Franz's, thought it was a nice place and wandered off into the woods."

As the leads dried up over the years, the RCMP eventually turned to an unlikely source for help—some 5,000 kilometres away.

Welcome to the Cold Case Academy

A lot of things had to break a certain way for the New York Academy of Art, a prestigious private art university in the heart of Tribeca, to begin lending its skillset to the investigations of more than a dozen Canadian cold cases.

About six years ago, instructor Joe Mullins and director of continuing studies John Volk were talking about offering a new course in forensic sculpture. Mullins had the idea of using real-life cases as the basis for the course, and contacted New York City's chief medical examiner's office, which just so happened to have recently acquired a 3D printer. The office agreed, and began scanning skulls from a number of open case files to send to the school.

Trained in a wide range of fine arts skills, students at the academy were already well versed in écorché, the art of drawing, or in this case, sculpting a human figure showing the muscles of the body without skin. "All of the students that go through our program have been trained in anatomy and all have done a little bit of sculpture. They all have skills that the average art student wouldn't," Volk explains. "They all think of this as pretty normal here, but in the reality of the broader world, it's pretty abnormal the training they get."

The program proved such a success that it was expanded to include skeletal remains from a variety of cold cases stretching from Delaware to California, including two 19th-century skulls from unknown soldiers killed during the American Civil War and an enslaved African man from Colonial-era Connecticut.

In 2018, the school also partnered with the medical examiner's office in Pima County, Ariz. to recreate the faces of eight unknown border crossers whose skeletal remains had been found in the harsh Sonoran Desert.

How the RCMP got connected with the academy was something of a stroke of luck. A few years ago, Cpl. Charity Sampson, with the RCMP's National Centre for Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains, happened to enrol in a forensic identification class at the academy. Mullins outlined the forensic sculpture course for her and said they were on the lookout for fresh cases.

"When [Sampson] was taking this class, she said, 'Wow, we happen to have some cases to work on.' It was through Charity Sampson's work that this program was put together," Volk explains.

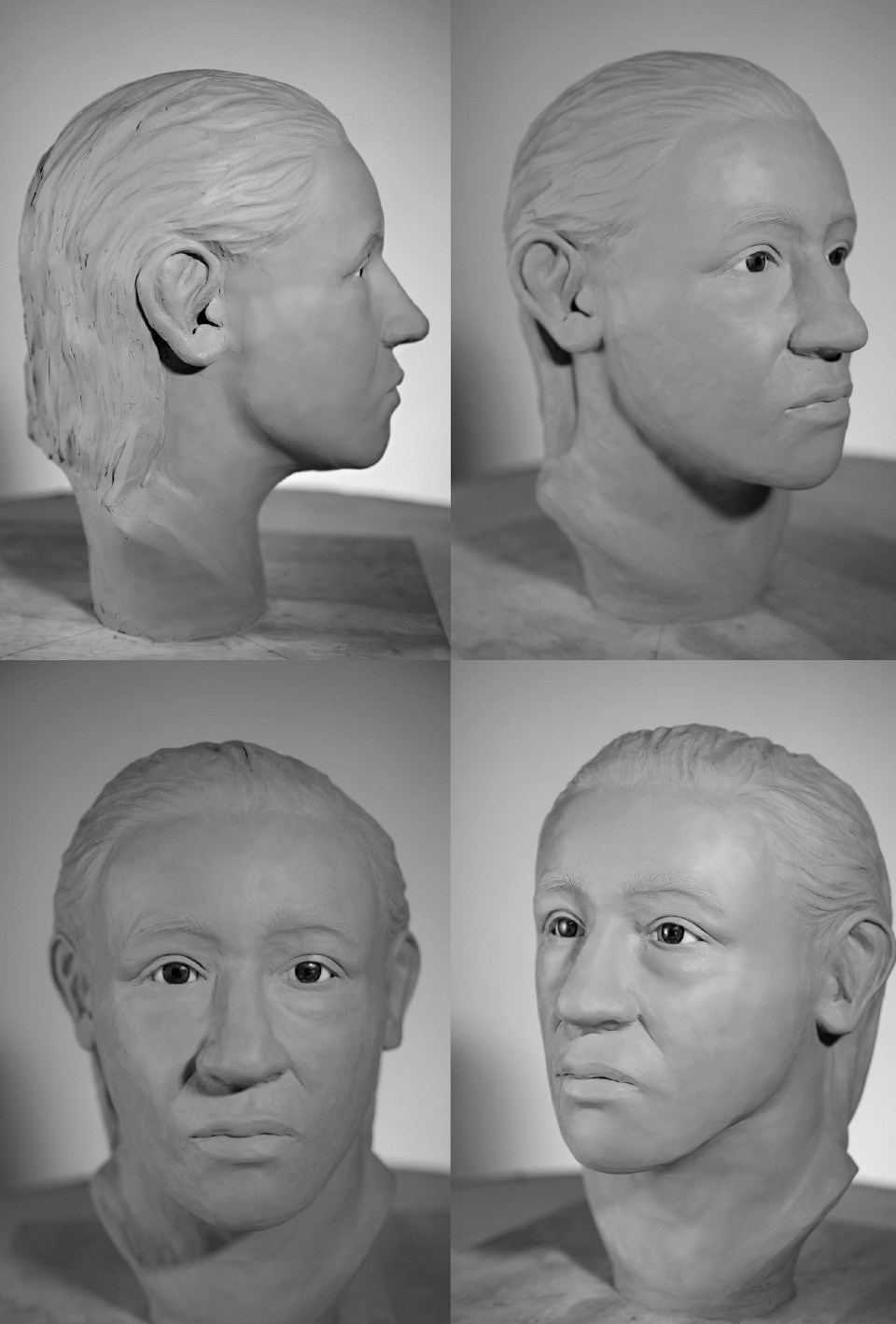

The RCMP provided the academy with 3D-printed versions of 15 male skulls located between 1972 and 2019—including Whistler's John Doe—chosen in part because they had fully enacted craniums and mandibles.

"Every face tells a story and these are 15 individuals who deserve to have their stories told," says Marie-Claude Arsenault, the RCMP's chief superintendent for specialized investigative services, in a release. "We started with unidentified remains, then a face, and we are hoping to end each of their stories with a name."

'It's suddenly kind of like a church'

It's through this unique joint initiative that 32-year-old Adam Lupton found himself staring into the eyes of the reconstructed face of a nameless bearded man last year, whose remains were located in West Vancouver in 1996. (The artist who recreated the face of the man discovered in Whistler in 1987 was unavailable for comment.)

A Vancouver native himself, Lupton never expected he would one day find himself working on active forensic cases when he enrolled at the renowned New York school.

"I'm not necessarily a sculptor; my main focus is painting, so I never thought, 'First, I'll sculpt and then I'll sculpt a cold case of an actual deceased person,'" he says. "I never in my wildest dreams thought I could do that or would have the opportunity to do that."

Each student is given a skull replica, and they begin by adding muscles to the face with clay, inserting small straws to mark tissue depth. Once the layer of skin is laid on, "you can really start to see how the skulls inform everything on top of it: how the cheekbones raise, how noses start to become more pronounced or wide or skinny," Lupton says.

At this stage, the sculptors rely on police case files to flesh out the remaining features. Wrinkles are placed to age the face appropriately, and other defining traits such as visible injuries or facial hair are added to get as close as possible to what that person might have looked like at the time of death.

"There's a hope that it's the right face or something close to the right face," Lupton says. "The entire scientific method behind it is based on approximations."

Unlike their usual artistic pursuits, the students have no room for creative license. "This isn't about, 'Oh, this person would look better if they had a bigger chin or if their cheekbones were set off a little bit," Lupton says. "We're not after making the best looking bust we can make. It's about making something that hopefully sparks an idea in someone to identify this missing person."

At a certain point in the process, a strange reality begins to set in for the students, who've been tasked with the immense responsibility of giving a face to the faceless. At the start of the week, they are just dealing with a 3D-printed skull, and no matter how distinct each skull might be, they are still no more than cold representations of a life that once was. But sometime around the third or fourth day, something changes. The faces start to become real, the recreated busts peering back at their creators with unwavering eyes. A knowing silence settles over the class.

"What I see happening is the first couple of days, there's a lot of chatter. Students are talking to one other and they're building the [busts]," says Volk. "Sometime either late Wednesday or early Thursday morning, they suddenly become individuals. Rather than having 15 or 16 students and an instructor, now there are 32 people in the room. It's suddenly kind of like a church. It's really quiet."

For most students, what begins as a novel weeklong workshop in forensic sculpting transforms into something much more profound. A bond is formed, and the artists can't help but wondering: Who was this person?

"Everyone tries not to, but you're spending so much time with this person who hasn't been seen for 10, 15, 20 years, and you have enough information in their case file that you can start to build a narrative or ask questions: What was their life like? How did they end up like this? You think of the possibilities," Lupton says.

"It is a connection you build, and over time, you empathize with this person."

In the more than three decades since Whistler's John Doe was recovered, police have chased down several tips from across the continent that have ultimately led nowhere. They've pored through missing-person records in both Canada and the U.S., to no avail. In 2013, a promising lead did emerge that investigators hoped would match the remains to a missing Toronto man. Unfortunately, DNA and dental records proved no match.

The New York Academy of Art program has had its successes, however. Since it was launched five years ago, there have been four positive identifications, including of remains found on a Nova Scotian beach last September that were matched to DNA evidence.

In the absence of so few biographical details, we have a tendency to fill in the blanks with our own speculation about a person's life, however outlandish, which often says more about us than it does about them. Theories abounded after Williamson and his supervisor discovered the remains near mid-station so many years ago. Some thought it was an arranged hit, like out of some noir crime flick, made to look like a suicide. Friends of Williamson joked he had found the missing American union leader and notorious mob target Jimmy Hoffa.

"It was certainly a popular cocktail discussion," he recalls.

"It's one of those little mysteries that will be part of Whistler lore."

For now, that's how Whistler's John Doe will remain—a mystery. But like the skull replicas that, over time, are given flesh and features that transform them into a reflection of a real life, we can only hope that for those who might still be out there, spending sleepless nights wondering where their loved one is, a sense of closure, however overdue it might be, is not far off.

If you have any information on this case, please contact the Whistler RCMP at 604-932-3044 or Sea to Sky Crime Stoppers at 1-800-222-8477 to remain anonymous.

'Is there someone out there still hoping he's around?'

It's a sunny spring day in April 2014, and Mark Steffens is out for his first bike ride of the season, eager to explore the trails around the Emerald home he and his family just moved into.

Near the end of the No Girly Man trail, he sees what appears to be a trail-builder's camp, flush with overhanging tarps and equipment. At first, he doesn't think much of it, and continues riding on. But something feels off. He wonders why someone would leave their trail-building gear out so early in the season, clumps of snow still dotting the trail. So he turns around to get a closer look.

As Steffens approaches the makeshift camp, he spots a clear layer of vapour seal, typically used to insulate homes, spotted with droplets of condensation. He notices a duffel bag, some boots, and a few other personal items.

"It started to look really odd," he remembers. "I started prodding around and actually grabbed a hand, or pushed onto the hand, at which point I realized it was a body."

Despite Steffens' initial fear that he may have stumbled onto a crime scene, police quickly ruled out foul play. The partial remains had been there since at least November 2013, when the man, Caucasian, between 50 and 65 years old with long grey hair in a short ponytail, was last seen leaving Nesters Market. Although numerous tips came in and a police sketch was circulated in the months after the man's death, no positive identification has ever been made.

Like his fellow John Doe discovered in the alpine almost 30 years earlier, it would seem the man sought out the beauty and solitude that Whistler offers to spend his final, lonely moments.

It's something that has weighed on Steffens in the years since, wondering if there are loved ones out there who might not know he's gone.

"[I have] these memories and this curiosity and this sadness around this person vanishing without any real family or any real impact from it," he says. "Is there someone out there who's still hoping that he's around, a friend or family member who is searching still and needs that closure far more than any of us do?"

Whenever tragedy touches our personal lives in the way it did for Steffens and Williamson, we have this innate desire to understand why. Maybe it's a way to reassure ourselves that we are different, that we will die at the end of a long and fulfilled life, surrounded by the people we love. But the truth is we are all closer to the darkness than we'd like to admit, something that has become readily apparent in the strange times we now find ourselves in.

One question that struck me time and again in reporting this story was this: were these men so far beyond the margins of society that no one—not family, not an ex-lover, not even a casual acquaintance—noticed, or worse, cared they were gone?

I couldn't help but be reminded of my older brother Chad, who wrestled with a laundry list of mental health and substance issues for much of his 34 years. When he died on a hot August day in 2013, he was also alone, and it took days for anyone to discover his body.

I think it was this painful memory, a few weeks before my own 34th birthday, that led me to ask Steffens a question that seemed to throw him for a loop: Was it important to try to keep the memory of these unknown men alive, to continue seeking answers, if only to give them the voice they never had in their lifetimes?

"For me, personally, I feel it's incredibly important what they're doing in case there is someone searching or looking for closure," he says. "But when it comes to the individual's legacy and giving that person a voice, particularly in my case, I don't think this person would care if he left a legacy."

Steffen's honest answer made me realize that, similar to funerals, this kind of quest for closure, vital as it is for the living, is of no use to the dead. And by the time they're gone, it's already too late to ask why.

Crisis Service Canada's suicide prevention hotline is available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year by calling 1-833-456-4566.