Have you ever wondered who pushed out the very first gondola car on Whistler Mountain's? Who was there? Or what the price of a lift ticket was?

As we know, there have been numerous visionaries since Myrtle Philip's pioneering days until now — all have participated in creating the Whistler we love. Many of those names are well known and fondly remembered around the valley in the parks and runs on both mountains.

But do we know the name of the person who pushed out the first gondola car on Whistler Mountain's official opening day?

Tony's tale

His name is Tony Biggen-Pound. I interviewed him back in the early 1990s and he's one of those people who I like to think of as "the extraordinary" in the ordinary.

Biggen-Pound was there from the beginning: earning $1.50 an hour. He worked on the construction site of the Gondola Barn and pushed out the first gondola car on Whistler Mountain's opening day.

In the summer of 1963 Biggen-Pound was working at the McGuire Sawmill, 10 kilometres south of Alta Lake. Workers at the mill learnt of a ski area development starting construction in the valley that fall. Biggen-Pound applied for work, and soon he was making the daily trip to Alta Lake.

Two years later, December 1965, Whistler Mountain opened for operations. Biggen-Pound did not ski his first winter working for Garibaldi Lift Company. In charge of T-Bar operations, he opted to snowshoe from the top of the Red Chair down to his workstation. Occasionally, the ski patrol would practice towing a toboggan and take Biggen-Pound for a ride. After participating in that twice: Biggen-Pound decided it was time to learn how to ski.

Biggen-Pound chuckled as he told how the Toilet Bowl earned its name. One summer, while his crew was working at Tower 9 on the Red Chair, blasting was occurring just above mid station. At the end of the day the crew opted to hike down to observe the progress. When they reached the bottom of the gully, one fellow looked back up the ravine and suggested they install a row of outhouses. He anticipated that skiers would need those facilities after they had skied the pitch. That soon became the summer's joke, and construction crews named the run the Toilet Bowl, though it was re-named the Funnel in 1992.

Originally a gasoline engine, with a manual three-speed transmission, powered the alpine T-Bar. The operator had to manually change gears according to the load on the lift. Approximately five metres of snow (15 feet) were required to open the T-Bars. One winter, the snow Gods provided over 18 metres (60 feet) of the white stuff and operators had to load skiers on at Tower 3, since the drive station, Tower 1 and Tower 2 were buried. The lift was kept operational by a tunnel that passed through the snow, enabling the cable and "Ts" to travel around the bull-wheel.

After the T-Bar was converted to diesel, fuel had to be delivered daily from the top of the Red Chair. It came in a 45-gallon drum, weighing 227 kilograms (500 pounds) and it was up to the ski patrollers to get it down to the T-bar each day in a toboggan. This was no mean feat. One day a patroller decided to take down two days worth of fuel in one trip. It turned out to be not such a good decision. When he approached the final pitch, he gained too much speed, causing him to become airborne. Suddenly, the drums broke through the base of the toboggan and sunk firmly into the snow. This furious patroller spent the afternoon digging the drums out.

Following that mishap the patrollers attempted to transport the drums behind a two-track skidoo. A wire cage was fitted around the drum with a tow yoke, enabling it to be rolled down the hill behind the skidoo. A whole week's worth of fuel could be delivered in one day. However, that solution only lasted until the next big snowfall, making the heavy load impossible to move.

Finally, it was decided to install two 5,000-gallon tanks with the engine connected directly to them. The tanks were filled every summer with enough fuel to last all winter. This arrangement lasted until the final solution in 1986: electrification.

One morning an empty T-Bar proved to be irresistible to a skier on his way by, especially with a long line up at the bottom. Grabbing the "T" the inevitable happened: the lift derailed causing instant shut down.

Biggen-Pound approached the man and noticed he had a company director's pass. However, it didn't prevent him from confiscating it. Biggen-Pound proceeded to inform the man he could pick his pass up at the end of the day. For the remainder of the afternoon Biggen-Pound was taunted by his co-workers, they wanted him to give the pass back, but he refused to budge.

At the end of his shift he gave the impounded pass to the president of Garibaldi Lifts, Franz Wilhelmsen.

One week later, as Biggen-Pound was wandering by the company offices, Wilhelmsen invited him to a company dinner. That evening Biggen-Pound was surprised to be dinning with all the current company shareholders and their wives. The director whose pass Biggen-Pound had confiscated apologized for putting him in that controversial position. Biggen-Pound worked for the lift company until the spring of 1968. He then chose a new career with the BC Highways Department.

Today Biggen-Pound is enjoying his retirement living in Squamish and being active in the local theatre community.

Featuring — Franz

Have you ever wondered how a Norwegian ended up at Alta Lake in the early 1960s?

Well, in 1940 Franz Wilhelmsen was serving in the Royal Norwegian Air Force stationed in Toronto. Here, during the war, he met and married his wife Annette.

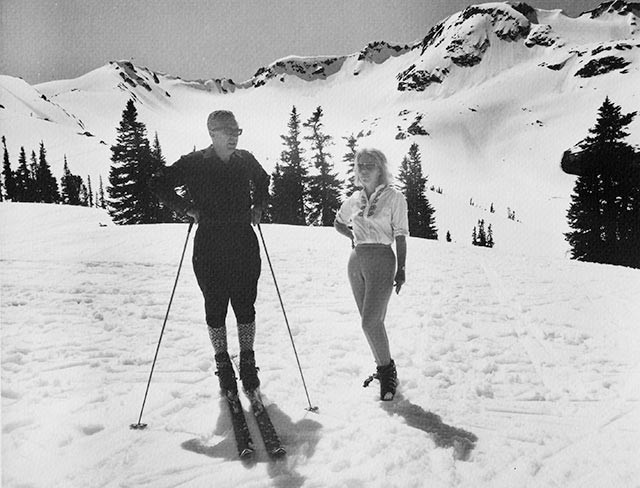

After the war, an enthusiastic skier, Franz found himself on Canada's West Coast, where he found the mountains of Vancouver's Lower Mainland too crowded. Escaping the hordes on Hollyburn, Grouse and Seymour mountains, he caught the Pacific Great Eastern train to Alta Lake, where he cross-country skied and enjoy the tranquility of the valley's outdoors.

Wilhelmsen soon recognized the number of Canadians who booked their ski vacations on charter flights to ski resorts in Austria and Switzerland. He soon convinced friends that Canada's mountains were just as good as those of Europe and soon after, history was about to be made.

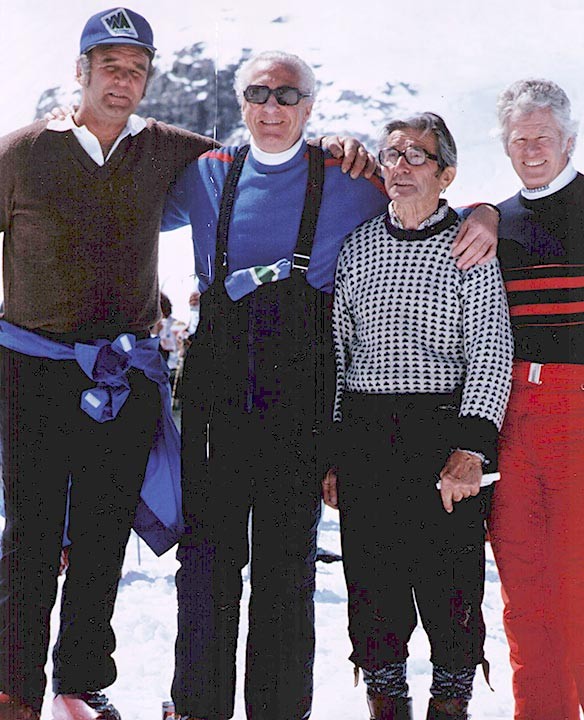

On Nov. 21, 1960 Garibaldi Lift Company was incorporated. The new company was headed by Wilhelmsen as president, who was also one of the original directors, along with Eric W. Beardmore, Peter J.G. Bentley, Bertram M. Hoffmeister, David Mathews, Glen W. McPherson, John S. Shakespeare, F. Cameron Wilkinson and Charles N. Woodward.

Their first priority was to hire Willy Schaefler, an expert in ski industry development. Schaefler had planned all the runs for the Squaw Valley Olympics and he was an authority in analyzing ski slopes and terrain.

For the next couple of years, Wilhelmsen trekked all over Whistler Mountain recording weather data, summer and winter, along with his good friend, Stefan Ples.

As conclusive evidence came in, Schaefler flew up to Alta Lake and over Whistler Mountain and penned a feasibility report, stating that Whistler Mountain had terrain to accommodate all levels of skiers. The combination of Vancouver's population and the fact that skiing was gaining in popularity, helped confirm their vision.

Wilhelmsen and Schaefler proposed the north side of Whistler Mountain be developed. The slope of the land would make lift installation more manageable. However, the government rejected that plan. Mining claims were already staked along the north side of the mountain. This forced the Garibaldi Lift Company to move to the southwest side of the mountain, to an area known today as the Creekside — without power, a water system or money, it was going to be tough challenge.

Financing was also hard to come by. Vancouver's local mountains were having operational problems of their own, resulting in investors being shy of this type of opportunity. It helped that the provincial government said that if capital for lifts and operations could be raised, it would put the highway through, and in 1964 the highway was started and paved in 1965.

Garibaldi Lift Company took immediate action and opted to go public to raise money. The directors masterminded a unique marketing plan offering company shares for $500. Shareholders would gain certain privileges, including that over the first five years they could purchase a season's ski pass for half price. This would result in a full return of their initial investment, because no brokerage firm was interested in handling this philosophy, the directors of Garibaldi Lifts promoted the plan themselves.

Once revenue flowed in, Wilhelmsen travelled to Switzerland to study the different types of ski lifts. He knew with the wet West Coast weather a gondola was a must. Eventually, Wilhelmsen went with Mueller Lifts from Zurich, Switzerland. The company purchased a four-passenger gondola — the first in the province of British Columbia — a double chair and two T-Bars. Soon after, falling trees for the lift lines commenced and runs began to take shape.

The land still belonged to the BC Forestry Department, so the slated areas had to be auctioned for clearing, but as luck would have it the logging company that won the bid to clear the trails went broke: leaving logs cluttered everywhere. That left Garibaldi Lifts free to hire local contractors to do the job.

Seppo's story and the early days

Seppo Makinen, a logger from Finland, was one of those contractors. Wilhelmsen met Makinen at the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) in 1962.

Garibaldi Lift Company had a booth at the two-week fair. Having foresight, Makinen introduced himself to Wilhemlsen, informing him he had been clearing the power lines in the Alta Lake area. On April 22, 1964, Makinen set up his tent, hired two crews, one in the valley and one on the mountain, and began working 12 hours a day, seven days a week, clearing logs. For the next 16 years Makinen worked on Whistler Mountain. In 1980 he cleared his last run under the Black Chair lift line that now bears his name: Seppos.

In 1965, word soon spread throughout the Lower Mainland that a new Whistler-based corporation was seeking employees. Young people flocked to Whistler Mountain looking for winter work. These workers became the first parking lot attendants and lifties in the valley.

Training the 100 employees took a tremendous amount of work. It was a learning experience for everyone — workers were even sent to Switzerland to learn the mechanics of operating and maintaining the lifts.

One unexpected setback was the telecommunication lines that came with the lifts. They were designed for a dry Swiss climate, not the wet Pacific coast weather ,and so the lines kept breaking from the weight of the snow. Consequently, the first maintenance workers, such as Doug Mansell, had to modify the Swiss design.

Mansell's family moved to the valley in 1944. His father, Jack, built Hillcrest Lodge on the southeast side of Alta Lake.

And when the lift company needed workers, Mansell applied and started as a lift operator. Eventually he advanced in the company and worked under Addi and Walter, two Swiss men sent over to manage and operate the lifts for the first year. Mansell took over as operations manager when the Swiss duo left and he kept that position for 18 years.

The mountain managers handled the general operations and the employees on a day-to-day basis while the corporate offices remained in Vancouver where the banks and lawyers were.

Before operations could begin, inspectors from the BC Ministry of Transport had to examine the lifts to give the needed certification. Wilhemlsen clearly recalled the snowy day the visitors from Vancouver drove up.

"When it was time for the inspectors to head back to the city, they could not locate their cars," he said. "Due to the heavy snowfall their vehicles were buried in the snow, resulting in an unexpected train ride home for the men."

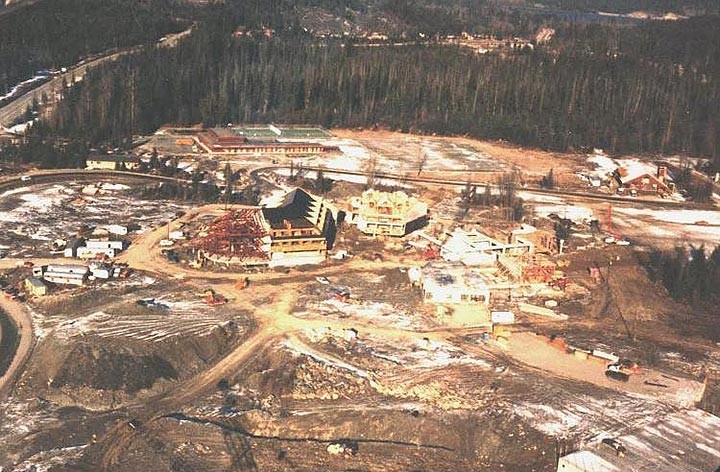

On Jan. 15, 1966, Whistler Mountain officially opened. Opening ceremonies were held at the base where the new Day Lodge and Gondola Barn were constructed.

Gerhard Mueller, owner of Mueller Lifts, travelled from Switzerland for the big day. He could not comprehend why Garibaldi Lifts had installed a lift with the capacity of 2,000 people per day, especially when only 400 skiers showed up and paid $5 a lift ticket.

But Garibaldi's directors, through careful planning, had calculated their operations (parking, ticket windows and restaurant capacity) in anticipation of two thousand skiers a day.

Their forward thinking paid off as skiing became a fashionable way to spend a winter weekend, and Garibaldi Lifts was extremely successful — making money in its first year. Money from ticket sales was transferred south once a week to Vancouver. All the revenue made was reinvested in the company, with the addition of more lifts and eventually the Roundhouse Restaurant at the top of the mountain. Sitting at 6,000 ft., skiers could warm by the fireplace and enjoy the spectacular view.

The idea of a year round resort soon began to evolve as the years passed.

Construction on the Arnold Palmer golf course began, but not until an extraordinary deal was made. Garibaldi's board of directors generously sold a quarter section of land east of Alta Lake to the municipality for $1, on the condition the provincial government sell the remaining needed property for $1. Therefore the golf course progressed — setting the foundations for a year round resort.

Five years after operations began, on Whistler mountain, the board of directors phased out the shareholders and an investment company from Toronto bought out the remaining shares. Hastings West, a group of Vancouver -based investors, purchased Garibaldi Lift Company in 1980; and subsequently, the name changed to Whistler Mountain Ski Corporation.

Wilhelmsen remained as president until he retired in 1987. He was thrilled when Snow Country Magazine rated Whistler the no. 1 ski resort in North America in 1991. Wilhelmsen passed away in 1998, not living to see the Winter Olympics brought to the valley, but his vision was lived out and he is to be remembered and honoured.

'Gone skiing'

There was actually a time in Whistler when proprietors would put up a sign on the their doors that read, "CALL LATER, GONE SKIING."

One of those local businessmen was Gordon Lampere Young, who owned and operated Whistler's first travel agency. Travel was in the family genetics. In 1927, Sid (a nickname he picked up in school) was born in Shanghai, China, to British parents. The Young family immigrated to Canada in 1939 and Sid immediately began to enjoy the surroundings of his new country. An outdoor enthusiast, he was soon skiing on Hollyburn and Seymour Mountains in North Vancouver.

His travel career began when he started working for Suntours, one of Canada's largest wholesalers in the travel industry at that time. He worked for the company for numerous years, but he really wanted to be in the retail end of the business.

Young's first trip to Whistler was in 1965. He loved the valley. And as time went on he became an active participant in the Olympic bids Garibaldi Olympic Development Association (GODA), prepared for the International Olympic Committee, and in 1973 Sid moved his family to Whistler. It was here he fulfilled his lifelong dream of opening his own agency, "Young's Travel," in November 1976.

Young's Travel opened for business in the Whistler Centre, across the road from the base of Whistler Mountain. Business was slow; thus, enabling Young to enjoy the fresh powder on Whistler Mountain. Always an avid skier, he planned to enjoy the finer things life offered in his new environment — his assistant would take care of the office while he was up on the mountain. It wasn't necessary for two people to be in the office.

Said Young: "All she had to do was call me on our walkie-talkie system and within seven or eight minutes I could be accommodating clients in the office." Once the transaction was complete, Young would place his "CALL LATER, GONE SKIING" sign on the front door.

His client list grew as the years passed, advertising in the local paper and on numerous billboards scattered throughout the valley.

One slogan worked particularly well — "Weather lousy today. Come in and book your vacation!" Young was astounded with the response he got on a rainy days.

At the office, Young could plan and book people's holidays, however, he had to travel to Vancouver twice a week to pick up the necessary tickets: manually written in those days.

Before Whistler evolved into a summer resort, the agency's busiest times were spring, summer and fall. Travel was easy to sell. It was a happy product. During those days, locals took one, two or three holidays a year. This was a part of the valley lifestyle. Packaged holidays, which included air and hotel, were always a success.

It was no secret that several residents collecting unemployment insurance could be found on the beaches of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. After two weeks they would return to Whistler get their checks, turn around and go back.

As Whistler expanded, so did the travel business. In 1978 Young opened his second office in Pemberton, 35 kilometres north of Whistler. However, he soon learned that the Pemberton market was too close to Whistler. Pemberton residents could book their vacation over the phone and pick up their tickets on their way through to Vancouver. After a couple of years he opted out of Pemberton and ventured to Lillooet, approximately 110 kilometres north of Whistler.

At that time the Duffey Lake Road was nothing more than a dotted line on the map. Therefore, every Thursday morning, Sid's wife, Erika, boarded the northbound train in Whistler and travelled to Lillooet. The office was located in the Camel's Foot Mall on Main Street. She opened for business Thursday afternoon, all day Friday and Saturday morning. On Saturday afternoon Erika would be on the southbound train for Whistler. When she was back in the office, she would process the tickets and take them to her customers on her next trip. The Lillooet branch was extremely successful.

In later years, a stiffer business attitude grew throughout the valley. Sid was one of the first enterprises to sign up in the new town centre. In 1980 he moved his office to the village. He leased 460 square feet of corner space next to the then Pharmasave drugstore and hired eight people: a valuable contribution to the local economy.

Throughout those years Whistler's population floated between 1,200 and 1,600 permanent residents. The airlines were in constant awe of the commerce his office generated. It was simply unheard of in the travel industry. Logistically, there wasn't the population to produce that kind of market. Often, rumours would filter down to Young that a competing agency was attempting to open. He made no bones about his economic concerns. Young worked exceedingly hard building his company and he fought to maintain its future, making a huge contribution to Whistler. From December 1978 until December 1982 he served the community working diligently as an alderman.

After 20 years of successfully operating his agency, Sid sold the business and retired in 1990. On July 14, 1994, Young passed away.

Whistler is not just a resort, it is a community, and its growth and success is due in part to all the people who have lived here and continue to live here.

Without the Biggen-Pounds, the Seppos, the Wilhelmsens and all the others who have blazed the trails for the snow sliders, Whistler would be merely a shadow of the community it has become.

Of course, this feature is by no means exhaustive and there are many others who have contributed to today's Whistler —

////////////////////

I would like to thank Tony, Franz and Sid for the time they gave me back in the 1990s when I was first writing, and so intrigued about the valley's history. And I must extend a special thank you to Sid, who granted me an internship at his travel agency. He offered me a full-time job; however, I wanted to explore the world, so he gave me the company deal on a one-way ticket overseas.

All photos are courtesy of the Whistler Museum. In 1986, Florence Petersen set about founding the Whistler Museum and Archives Society (WMAS). Located in a small room at the back of the library, it gradually grew until more space was necessary. The municipality then rented the old municipal hall, located on Highway 99, opposite Function Junction, 10 kilometres south of the village. Hours of volunteer labour were given from individuals like Bill and Elaine Wallace. The Rotary Club, led by Bill Wallace and Florence's husband Andy, provided funding and assistance, enabling the project to transcend from a dream to a reality.

Today the museum is located at 4333 Main Street, behind the Whistler Public Library and just beside the Pinnacle Hotel. Go to www.whistlermuseum.org for any further information.