Last spring, as the first wave of measures to halt the spread of coronavirus kicked in, travel screeched nearly to a halt, and the hospitality and tourism industry slowed considerably. Locals in public-land gateway towns predicted doom—and also breathed a big sigh of relief. Their one-trick-pony economies would surely suffer, but at least all the newly laid-off residents would have the surrounding land to themselves for a change.

For a few months, the prognostications—both positive and negative—held true. Visitation to national parks crashed, vanishing altogether in places like Arches and Canyonlands, which were shut down for the month of April. Sales and lodging tax revenues spiraled downward in gateway towns. Officials in many a rural county pleaded with or ordered non-residents to stay home, easing the burden on the public lands. It was enough to spawn a million #natureishealing memes.

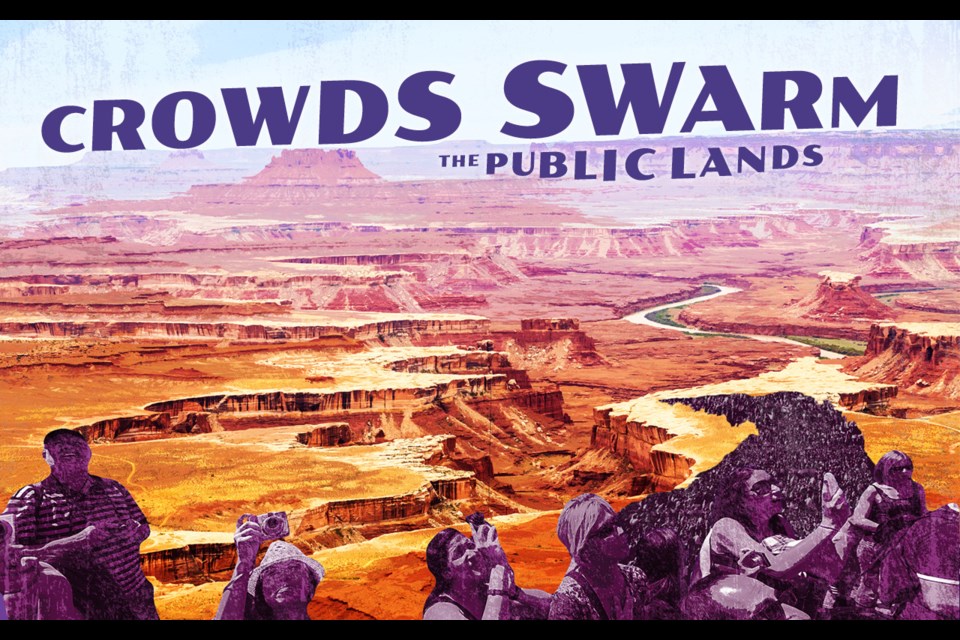

In the end, however, the respite was short-lived. By midsummer, even as temperatures climbed to unbearable heights, forests burned and the air filled with smoke, people began traveling again, mostly by car and generally closer to home. They inundated the public lands, from the big, heavily developed national parks like Zion and the humbler state parks, to dispersed campsites on Bureau of Land Management and national forest lands.

It was more than just a return of the same old crowds. Millions of outdoor-recreation rookies apparently turned to the public lands to escape the pandemic. Nearly every national park in the West had relatively few visitors from March until July. But then numbers surged to record-breaking levels during the latter part of 2020—a trend that was reflected and then some on the surrounding non-park lands.

If nature did manage a little healing in the spring, by summer the wounds were ripped open again in the form of overuse, torn-up alpine tundra, litter, noise, car exhaust and crowd-stressed wildlife. Human waste and toilet paper were scattered alongside photogenic lakes and streams. Search-and-rescue teams, most of which are volunteer, were overwhelmed, with some being called out three or more times a week. Meanwhile, the agencies charged with overseeing the lands have long been underfunded and understaffed—a situation exacerbated by the global pandemic. They were simply unable to get a handle on all of the use—and increased abuse.

There is no end in sight: The first five months of 2021 have been the busiest ever for much of the West’s public lands. And tourist season has only just begun.

Nevada

The Las Vegas tourism and gaming industries took a massive hit in 2020, as visitation plummeted by 55% compared to 2019. Only about 42% of the city‚‘s 145,000 rooms were occupied, on average; lodging tax revenues were less than half of normal. At the same time, crowds converged on the area’s public lands like never before.

10,000 Estimated number of people who entered the Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area near Las Vegas on a single day in April 2020. The Bureau of Land Management temporarily closed the scenic loop road in response and implemented a timed-entry reservation system.

Montana

30% Increase over previous years in number of applications for nonresident deer and elk-hunting permits for 2021.

Oregon

Oregon‘s state parks were getting overrun by out-of-staters, leaving no place for residents to recreate or camp. So, in August, state officials upped camping fees for non-residents. Even if it doesn‚‘t deter people form visiting, it might help make up for the state parks’ $22-million budget shortfall.

Utah

9 Pounds of human waste a Zion National Park ranger collected along a single stretch of trail late last year. He slaos cleaned up more than 1,000 drawings or etchings people had made on the rock.

The volunteer search-and-rescue team in Washington County, Utah, responded to 170 incidents in 2020, exceeding the previous record by almost 40 calls.

Visitation at Utah’s state parks in 2020 was up by 1.7 million people from 2019, with some parks, such as Goblin Valley, being two to three times the number from previous years. Judging by this spring, that new record is likely to fall in 2021.

Idaho

7.7 million Number of visitors to Idaho’s state parks in 2020, a 1.2-million jump from 2019, which itself was a banner year. “It‘s a mind-boggling number,” said Brian Beckley, chairman of the Idaho Parks and Recreation board, in a news release.

Colorado

On the busiest days prior to 2020, up to 200 people made the trek to Ice Lake Basin in southwestern Colorado. But late last summer, 400 to 600 people per day inundated the place. In October, a hiker started a wildfire that burned 500 acres and forced the helicopter-assisted evacuation of two dozen hikers. This summer, the trail is closed.

23%Amount by which 2020 visitor numbers at Colorado state parks exceeded those from 2019.

For years, most of the public lands around Crested Butte, Colorado, have been open to dispersed camping. But after the free-for-all got out of hand in 2020, public-land agencies halted dispersed camping, designated a couple dozen sites and implemented a reservation system. By April, all of the sites were booked through Labor Day.

12 Number of avalanche-related fatalities in Colorado during the 2020-21 winter, matching the record high (since 1950) set in 1993.

34 Number of drownings on Colorado‚‘s lakes and streams in 2020, a record high.

Wyoming

Last year was a banner year for Wyoming’s state parks, which received 1.5 million more visitors than in 2019. But thanks in part to waning revenues from taxes and royalties on fossil fuels, state lawmakers slashed the Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources budget by $1.1 million this year.

28,890 // 43,416 Number of visitors who entered Yellowstone National Park during Memorial Day weekend 2019, and 2021, a 50% increase.

Westwide

28% Amount by which camping participation in the United States grew during 2020, which adds up to about 7.9 million additional campers.

10-14 months Approximate wait time to get a modified van from Storyteller Overland, which makes Mercedes Sprinters #vanlife-ready. Storyteller COO Jeffrey Hunter told KIRO Radio that coronavirus-related demand for the vehicles—priced at $150,000 to $190,000—has surged so much that the company doubled its workforce.

This story originally appeared in High Country News on June 18. Read it at hcn.org.