Mountains are creations of nature. But ski mountains are birthed by people. Blackcomb Mountain was fathered by two men. Without their mix of vision, political arm-twisting, cussed determination and pure, blind luck, Whistler the town, with but one mountain, probably wouldn’t be anything like what it is today.

Al Raine envisioned a village where a garbage dump was. The village he saw was nestled between two great ski mountains, one in operation, the other operating in his imagination. In his role as provincial coordinator of ski development, he sold the government-of-the-day on the idea of supporting the development of Blackcomb.

Hugh Smythe built Blackcomb because, well, he was destined to. His fate was set as a teen working volly patrol at Mount Baker. It was fuelled in Whistler Mountain’s opening year, 1966, and indelibly cast when he became a pro patroller a short time later, an experience he described as, “flying around in helicopters, dropping bombs, chasing women, and skiing every day.”

Fortunately for all of us, Smythe was a closet businessman, and a few years later, only 26, was running Fortress Mountain in Alberta. Bankrupt, owned by the Federal Business Development Bank and in shambles, Smythe got it opened and steered the bank toward Aspen when they wanted to get out of the ski business.

Meanwhile, Raine had convinced the B.C. government developing Blackcomb made good sense. When the final decision to proceed was made in the waning weeks of summer, 1978, two bids were submitted to develop the mountain. The final decision was made later that autumn; the bid from Fortress Mountain, backstopped by Aspen, with Smythe as the point man, prevailed.

Raine said it came down to a matter of choosing a proven resort operator. Smythe simply said: “Let’s get to work.”

“I’d have to admit that back in‘78 when we started the planning and working on it, my vision for Blackcomb certainly didn’t come anywhere close to where it’s since grown to be,” Smythe said.

Imagine a mountain: trees, rocks, streams, elevation gain, cliffs, more trees. Imagine turning the mountain into a ski area—runs to lay out and cut, lifts to plan and install, restaurants to build, menus to tweak, people to hire, a million and one decisions to turn a forest into a playground.

“Operations is one thing,” said Smythe. “But going in and developing an evergreen project, cutting trails, hiring contractors and logging companies are all big decisions. We had to be on time and on budget to open for 1980. It was scary stuff.”

While still notionally in charge of Fortress, Smythe took up residence in White Gold, fired up his old Tucker snowcat and grinding up a “road” he’d had Seppo Makinen cut, skied every day trying to get a feel for the mountain. Between those excursions and hiking in summer, he gained a sense of where to cut runs. Logging contractors were hired and runs soon began to take shape on the lower flanks of the mountain.

“Starting from scratch, we were able to design and build something that worked,” Smythe said. The intermediate cruising was splendid, but variety still outweighs good design and until we were able to get more variety, we were always going to be the underdog.”

But variety would have to wait. Key people had to be hired, a ski school established, rental skis secured and everyone trained to manage skiers’ total experience. Had Blackcomb been anywhere but across Fitzsimmons Creek from Whistler Mountain, what they were about to open would have been sufficient, even superb. But with Whistler’s high alpine bowls, two downhill aspects and a 15-year head start, it was going to be difficult just to put in a solid No. 2 showing.

“It was a challenge to figure out how we would compete,” said Smythe, who placed his bet on better marketing, better customer service and better food. Ready to open for the 1980 season, all they needed was snow and skiers.

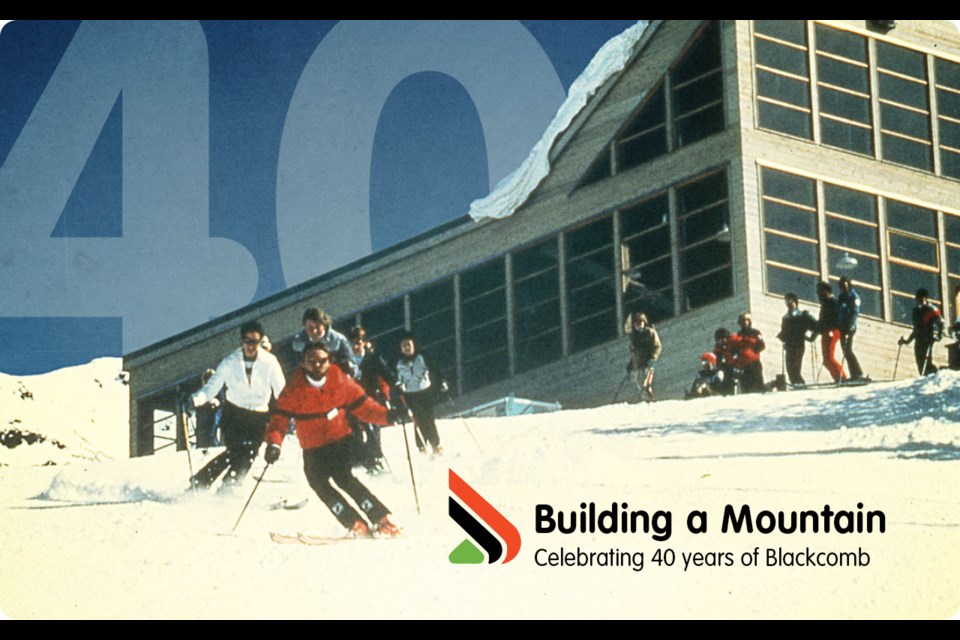

Franz Wilhelmsen must have gotten a chuckle out of Blackcomb’s marketing literature that first season in 1980. “Over 4,000 feet of soul-stirring skiing,” it proclaimed, with 350 acres (142 hectares) of skiable terrain. The uppermost runs just touched treeline on some of the steeper pitches. The 33 kilometres of runs were 75-per-cent beginner and intermediate. The rest, deemed expert, was considered an overstatement in the minds of many.

But Blackcomb was the new kid on the block and received a big boost from the developing Whistler Village where the aptly named Lift 1 was anchored. The daylodge, guest services, ski school, administrative offices and Rendezvous 765 were located up the mountain where Base II stands today.

So was Lift 2, a 10-minute ride to Lift 3, itself granting access to Lift 4. The ride from Village to Elevation 1860, the restaurant at the top—guess how high it was—took 37 minutes. But within the context of the mountains of its day, and certainly compared to the lifts on either side of Whistler, pokey fixed-grip chairs and long rides were nothing out of the ordinary

Thirteen bucks bought a day’s skiing, $5 for children. A season’s worth of fun could be had for $300. The core runs of the early mountain were the fall-line, intermediate cruisers familiar today: Choker (currently the terrain park), Springboard, Gandy Dancer (sometimes called Ross’ Gold) and Cruiser. That was about it for skiing.

What little skiing was being done, that is—1980 was not a good snow year. Good rain year though. But with no alpine to get above the rain, Blackcomb was off to a slow, soggy start.

“When Blackcomb first opened, we had phenomenal conditions on Opening Day, Dec. 4, right through until Christmas. Top-to-bottom skiing. It was just amazing, and then it started to rain and washed not just half the mountain, but three-quarters of the mountain was barren green, into early March,” recalled Smythe. “We had spent three years planning and building and to have that all washed away, that was a pretty big setback.”

Arthur De Jong, then a patroller, recalls the mountain throwing a party the first time they broke 2,000 skiers in one day. He also recalls a warm spring day when he and future mayor, Hugh O’Reilly, got their golf game ready for the summer by driving balls off the deck of Elevation 1860 down into Jersey Bowl. “The only thing we could hit was another staff or more likely a raven,” said De Jong.

That first year, Blackcomb clocked about 54,200 skier visits, well below its projections of 225,000. Whistler? 320,000. But Smythe had beaten the odds, opened on time and developed a small core of Vancouver skiers who liked the service on the mountain and preferred its intimacy and lack of crowds.

Fortunately, they came back. With virtually no changes to the physical layout of the mountain, visits during the 1981/82 season almost quadrupled, to just over 205,000. The worries of the first season were beginning to fade and it was time to think about expansion.

A new lift opened the 1982-‘83 season. Planted at the bottom of the flats below Jersey Bowl, it accessed terrain previously skied only by ski patrol and powder poachers, including the serious powder chutes of Blowdown, Staircase and The Bite. Powderhounds not averse to some hiking and a potential run-in with patrol discovered the Saudan Couloir, Secret Bowl, Cougar Chutes, Pakalolo, and others.

But despite new lifts, better grooming, a popular race program and some alpine skiing, Blackcomb wasn’t the mountain Hugh envisioned. “We couldn’t compete with Whistler without more variety. We were boring. The alpine was up there; it just had to be realized.”

Peter Xhignesse realized it. A patroller and trainer, Xhignesse had explored the far reaches of Blackcomb’s terrain, particularly the expansive, south-facing slope that fell away towards Fitzsimmons Creek. He pitched it to Smythe, who was skeptical but had a habit of listening to his people. After some recon and a lot of thought, the conspiracy was hatched.

Smythe remembered a T-bar he’d installed at Fortress that was no longer in use. Assuming Aspen’s support and not going into the messy detail, “It just disappeared.” Reputedly under cover of darkness. Xhignesse thought it would make a nice addition.

Contrary to Hugh’s assumption, Aspen refused to fund the undertaking. Hugh said he’d sell enough incremental season passes—$380 for early birds—to pay for it. He did and the Mile High Mountain was opened in 1985. Whistler was changed forever and the race was on.

But, perhaps foreshadowing future developments, Aspen was growing weary of its Canadian outpost. They wanted out.

Fortunately, a guy named Joe, who had a thing about real estate development, wanted in.

With Blackcomb finally showing promise and Joe Houssain having previously wanted to develop Whistler itself, Smythe had found someone to buy out Aspen’s interest in the mountain. With the deal inked in the summer of 1986, the stage was set and the good times started to roll in earnest.

The 1986-‘87 season saw modest expansion on the hill but many plans behind the scenes. Despite that, and despite Whistler’s new Peak Chair, Blackcomb cracked 40 per cent of total skier visits, confirming everyone’s faith in the future.

Opening Day 1987 changed everything though. Blackcomb arrived and arrived in a big way thanks to Smythe having hired Paul Mathews of Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners fame, who finally got the opportunity to realize the vision he had for Blackcomb when he was instrumental in the initial losing bid to develop the mountain. The Wizard, Solar Coaster and 7th Heaven Express—all newfangled detachable quads—started turning on Opening Day... fast. A ride that had taken 40 minutes on many chairs now took 14. A new Daylodge, base bar and much larger Rendezvous greeted skiers. And a new T-bar up Horstman Glacier opened up much more alpine skiing.

Blackcomb had arrived. Whistler took notice, especially when Smythe racked up 54 per cent of skier visits that year. Better skiing, better lifts, better food, better grooming, better snowmaking made not noticing Blackcomb impossible. The centre of gravity was shifting quickly.

“It was always competitive with Whistler, but the emphasis on customer service and some of the operational innovations, I would say was the catalyst that led to so many great things at the resort,” Smythe said. “Not that Blackcomb caused the village to be built, but without the development of Blackcomb, I’m not sure the village would have gotten built or would have been as successful.”

But that was just the start. Houssain and Smythe convinced Canadian Pacific Hotels to build a new, luxury hotel at the base of Blackcomb. It would anchor a whole new village of condo developments that sprang up like autumn mushrooms. The Upper Village on the Benchlands supercharged further development and ensured thousands of skiers would stumble out of their lodging right onto Blackcomb’s lifts.

More improvements followed. Showcase T-bar opened Blackcomb Glacier and jaw-dropping terrain. Crystal Chair opened up 568 more acres (230 ha.) and gave access to a whole new aspect of the mountain. It could have ended there and no one would have complained.

But Smythe had one more trick up his sleeve, one that had been there since 1978. A chance meeting in Tokyo in 1993 led to Nippon Cable—the Japanese representative for Doppelmayr lifts—purchasing 23 per cent of Blackcomb. Their investment, $25 million over five years, fuelled Hugh’s dream of a lift running into the high alpine of Horstman Glacier. Glacier Express was born.

It was followed in short order by the retirement of Lift 1, replaced by Excalibur Gondola, which begat Excelerator Express, which led skiers to the expansive Glacier Creek restaurant. Infilling followed but Blackcomb was, for all intents and purposes, built. Whistler’s destiny was cast.

But then, an unlikely rumour came true. In December 1996, Blackcomb ate Whistler and the two best ski mountains in North America came under single ownership.

Compared to that single decade of meteoric rise, things have been relatively calm on what is still referred to as the Dark Side by long-time Whistler skiers. Intrawest has come and gone, another outrageous rumour came to life when the Peak 2 Peak Gondola stitched both mountains together, Smythe retired, former COO of Whistler Blackcomb Dave Brownlie left his mark on the new WB and moved on as well. Mountain ownership passed through various monied interests then enjoyed a brief moment as a public company, always with Nippon Cable in the background with a significant ownership stake.

And now, Whistler Blackcomb is an arrow in the ever-expanding quiver of Vail Resorts. The latest owners have replaced the game-changing lifts rising from the Benchland base. The 10-person gondola—pre-pandemic capacity—replacing the Wizard and Solar Coaster has proven popular, after much angst and a shaky first season. Pokey old Catskinner is now a realigned quad. Tweaks here, tweaks there.

Several generations have grown up not knowing a time there wasn’t skiing on Blackcomb. One generation has grown up not knowing when the old established mountain and the unlikely upstart were in fierce competition with each other. The cooperative Dual Mountain is the punchline of an increasingly inside joke.

And Hugh? He’s still around. Skiing most days, on Blackcomb, of course. Wondering how it all happened in the blink of an eye.

“Change is always a challenge,” Smythe said. “But this is still a phenomenal place to live and work and play. I’d say maybe it’s hidden a little, but if you peel back the layers of the onion, the bones of the resort are still very good.”

There will, hopefully, be some kind of socially distanced, virtual celebration to commemorate Blackcomb’s 40th. How could it be otherwise? Whistler without Blackcomb? Unimaginable.

-With files from Brandon Barrett

G.D. Maxwell wrote about the development of Blackcomb in Pique Newsmagazine’s 2000 publication, Whistler: A History in the Making, which helped inform this feature.