Tucked into the corner of a windowsill in Chief Dean Nelson's Mount Currie office sits a large, grey rock shaped like a vase.

"It is beautiful as is, but the strange thing is, it's not from here," says Lil'wat Nation political chief Nelson from his office chair, examining the object. "It was brought here from the Powell River area. It's interesting how things get moved. People take things for their own reasons and values (with) little or no consideration (for their) home. It doesn't belong here. Its home is with the Sliammon people."

A non-Indigenous person reportedly took the stone from Powell River—more specifically the Sliammon First Nation—but when it began to bring hardship and bad luck, they turned it over to the Lil'wat.

"They wanted someone to take care of it, at least away from them," Nelson says. "I have no wishes or bad intentions with the stone figure and it has not affected me negatively. I've contacted the leadership of the Sliammon people and only wish for it to be returned to its origin. I feel very strongly about returning things to where they're supposed to be. It's a significant piece of someone's culture that's been taken from someone. Obviously, their values were never considered."

That concept of repatriating items, art and artifacts has been top of mind for Nelson lately. Earlier this year, he put out a press release calling for anyone with historical Lil'wat possessions—whether they were found, bought or gifted—to return them to the nation.

Both individuals and organizations have told the nation of historical possessions in their hands, but because they had been bought or found, they didn't think too deeply about where those items were from or what they symbolized. Part of Nelson's challenge now is to convey that meaning to people.

"It's a piece that's been taken," he says. "There's a piece missing. It's identity, it's cultural significance, it's everything. It pertains to our Indigenous values. (The items) are benefitting somebody, but not the people who brought them to life. The real purpose and significance of the cultural articles are left to interpretation. We're at a loss for someone else's gain. We have identity loss, a cultural loss. We are at a spiritual loss."

He continues: "The Ucwalmicw are putting the cultural pieces back together, but presently we're at a loss because of someone else's value. The values are in people's homes; they're on display as a decorative project. At present, in museums, people pay to see these exhibitions. They have a different value there, but we have not had them on display for our people to see?"

Nelson says he's heard of Lil'wat possessions on display in museums as far away as Philadelphia, New York and Washington, D.C. but they've had little recourse for repatriating them. Lil'wat members have also found traditionally weaved baskets in places such as the Re-Use-It Centre in Whistler and shops in Vancouver.

There are also stories floating around of locals—largely in Pemberton—in possession of artifacts.

"I know of people in the corridor recently that have followed through with building on (top of) significant cultural sites without reluctance, without regret," Nelson says. "Cultural items were dug up and disposed of or were kept for personal reasons. Some of these incidents happened within the last 15 years and (they) were never approached for wrongdoing through archaeological laws or any laws that were supposed to protect historical, sensitive sites or materials."

A 'worldwide' movement

In his press release, Nelson cites several articles from the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People requiring "states ... to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with Indigenous peoples concerned."

The declaration isn't legally binding—though signatory countries have committed to upholding it. But a new private members' bill could help the Lil'wat—and other Indigenous communities in Canada—repatriate cultural property to their territories.

Bill Casey, a Liberal Member of Parliament for the Cumberland-Colchester riding in Nova Scotia, first introduced Bill C-391 as a private members' bill in February 2018 after visiting the Millbrook Cultural and Heritage Centre in Millbrook, N.S.

"They have this nice display case with a robe behind glass," Casey recalls. "I was admiring it one day and the curator, Heather Stevens, said, 'That's not the real one. The real one is in Melbourne.'"

As it turns out, an Australian museum had been in possession of the Millbrook First Nation ceremonial garment for the last 126 years.

That didn't sit right with Casey.

"They had nothing to work with—no tools," he says. "My idea was to give First Nations like Millbrook a hand, somewhere to turn to. If they identified an artifact that's available, they could come to this agency and say, 'This is what we need for transportation' and get advice and some help."

Casey has since set to work introducing Bill C-391: Indigenous Human Remains and Cultural Property Repatriation Act.

He was taken aback by the feedback he quickly received not only from Parliament, but also from leaders, media and institutions from around the world. There was a call from the Commonwealth Museum Association asking to use his bill as a template; there was media coverage in China (though Casey only recognized the image of the Millbrook robe and his name), and even calls from the Netherlands.

Clearly, he had tapped into a bigger global issue.

"The repatriation of Indigenous artifacts is a movement around the world," Casey says. "It turned out to be a big deal. We talked to a lot of Indigenous people and museums and leaders from across the country. It was the most fascinating learning experience for me to hear what Indigenous people have to say about artifacts. They're not just artifacts; they represent the spirit of the people who made them and cared for them. I had never been exposed to that perspective."

The bill seemed to come at the right time. It passed first and second reading and then went to a committee with voices from both Indigenous and museum representatives.

It passed third reading unanimously—a rarity for a private member's bill—this past February.

"I think the timing just happened to be right," Casey says. "People are ready to do this. We've got (the) Truth and Reconciliation (Commission); they all fit together. Certainly artifacts are a big part of reconciliation."

While the bill is still being reviewed in the Senate, it is expected to pass by the summer. After that, Casey says, the government will have three years to create the framework to carry out repatriation efforts. "I was just really pleased it went the way it did and I'm pleased for the people who will be able to repatriate the artifacts," he adds.

As for the Millbrook First Nations' robe? Shortly after Casey set the bill in motion, the Australian ambassador to Canada reached out to him: she had talked to museum officials, who were eager to return the item.

Now, a member of the Mi'kmaq First Nation band in Millbrook and an Indigenous Australian woman who works at the museum are handling the logistics involved with returning the item to its rightful owner.

Meanwhile, the bill that story spurred will create a strategy with five measures planned: To put into place a mechanism for First Nation, Inuit or Metis communities or organizations to acquire—or reacquire—cultural property or human remains; to encourage anyone in possession of remains or property to return them; to recognize the importance of preserving those remains and cultural property; to respect traditional Indigenous knowledge of cultural possessions rather than requiring strict documentary evidence with regards to repatriation; and to help resolve any conflicts that arise with remains or property in a respectful manner.

Still, Indigenous communities face a huge challenge trying to determine what, exactly, has been taken and who might be in possession of it.

That's what the Lil'wat Nation is currently grappling with, Nelson says.

The first step, he adds, is to make the Sea to Sky corridor aware that based on reconciliation measures and protocol, these cultural items bought, found, and taken should be returned to the First Nations people who created them.

"I'm very optimistic," Nelson says. "I believe in people ... That's all you can do—put your intentions out there and believe people will do the right thing."

Following damaging government policies—from the ban of the potlatch, in which nations were prevented from taking part in the gift-giving feast traditionally practised by Indigenous people across the Pacific Northwest, to residential schools to the myriad injustices within the Indian Act—that aimed to strip Indigenous people of their culture, repatriation of cultural possessions means more than just giving back an item.

"I do want those things for our future," Nelson says. "I feel that all of our creations have to come back here. They've been away for a long time ... This repatriation is just an awakening of this. Understanding needs to be emphasized that reconciliation is not just a word, but an action to correct wrongful practices. The history of all ... incidents and occurrences that have put First Nations' people on Indian reserves under the Indian Act system (are) not fully understood or comprehended by the general public."

The complications of repatriation

Connecting with individuals in possession of these items is one issue, but many museums in Canada have their own policies around repatriation, says Susan Rowley, a curator at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia and chair of the museum's repatriation committee.

"I've seen a number of wonderful cases of people stepping forward and saying, 'We've found this in our house' or 'We've had this in our home and we'd like to return it to this nation,'" she says. "We do get calls here or emails saying, 'We have this in our family and we're thinking about where it should go for the next generation.'"

Often, the museum is able to at least narrow down the area from which the items might have originated, she adds.

But it can be a complicated issue. She cites the example of First Nations women who would trade clothing for baskets in the late 1800s and early 1900s. "Then that basket is in the settler family. It's now lived in the settler family for three generations. It has acquired a value to that family," she says. "They view it as part of their heritage. For them, sometimes, the idea of giving that up is hard. For others, they love being part of that idea—they love reconnecting it with the family or community where the basket originally came from. We're seeing more of that."

As for museums, they're slowly beginning to realize they have to balance representation with reconciliation and work with Indigenous communities in order to display their possessions properly. "It's not solely about repatriation," Rowley says. "It's about relationships, reconciliation, and representation."

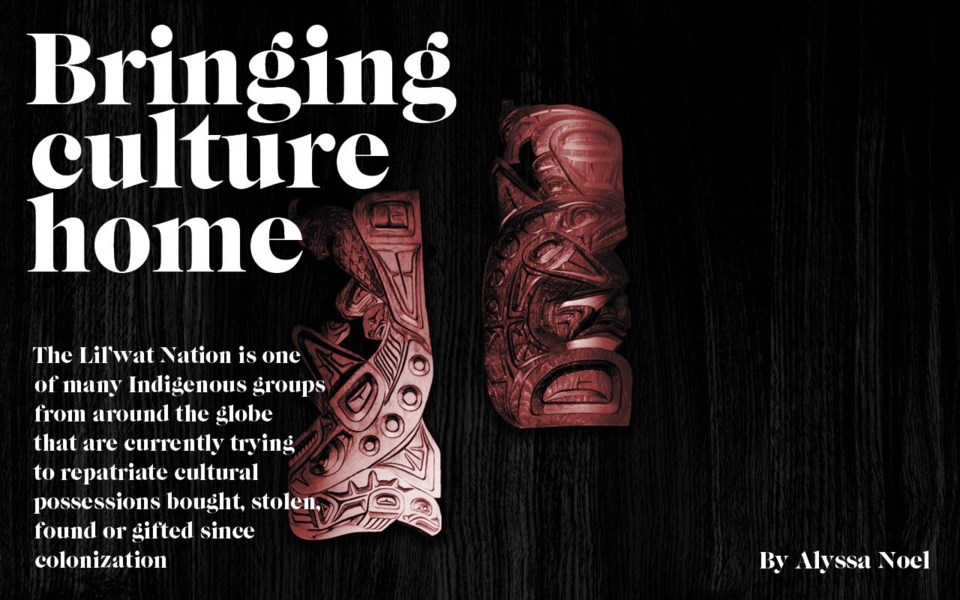

Nelson's ultimate goal is to have Lil'wat Nation possessions—from baskets to bowls to stonework and masks—returned and displayed on Lil'wat territory so the nation's children can identify with them and further embrace their culture.

Having worked as a teacher before being elected chief, Nelson returns to the Xetólacw Community School in Mount Currie about once a week to take part in songs and dances.

"The hope is to display the cultural creations together," he says. "They belong to the people and the people should know where (the rest) of their cultural heritage is being kept and have access to (it). There are things that have been returned (by) people who have bought things from collectors to give them back to the community and we are very grateful. There was a shift in value centuries ago that has never balanced out. Even today, cultural values are not seen as equal ... The message is anyone who has a cultural creation in their possession needs to return it to the people of origination for proper protocol and spiritual practice."

If you have any items you think might be from the Lil'wat Nation and would like to repatriate them, email [email protected] or call 604-894-6115.