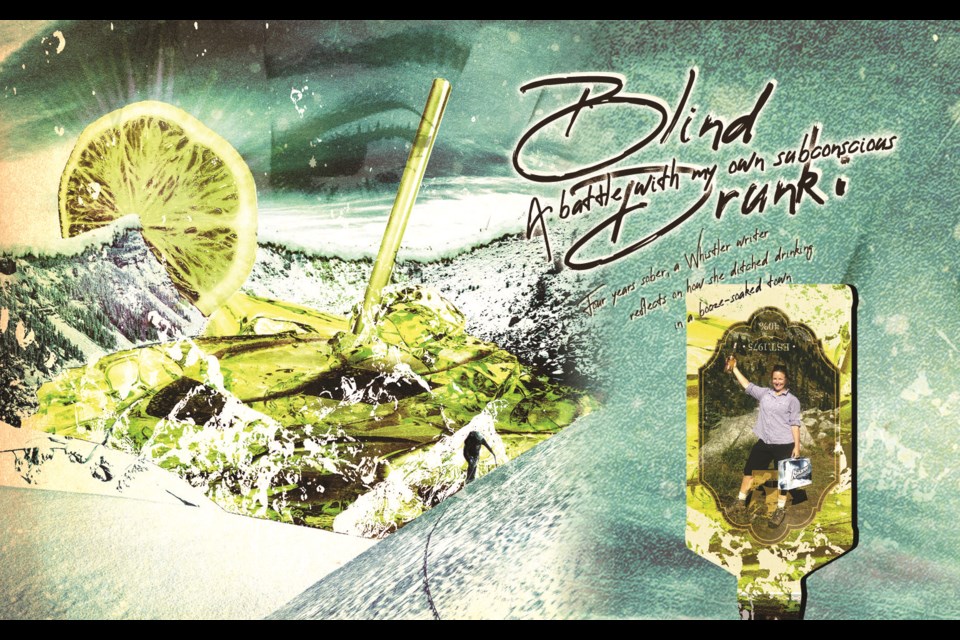

My dad kept a jar of peanut butter in his glovebox to mask his booze breath in case he ever got pulled over. This was required at all times of day because he was always some level of drunk. You’d think watching my highly successful parents descend from a lavish, affluent international existence into deep alcoholism, poverty and homelessness would have made me wary of my own relationship with booze. Cue the mid-1990’s and an impromptu move to Whistler as a 20-year-old from out east, laden with college debt.

I quickly learned that drinking regularly is steeped in the routine here and goes hand in hand with mountain adventure, and I was onboard. For years, there were great parties with copious amounts of booze—but mostly it was about social drinks after work or play, generally limited by the funds in the bank. There was never a ski day, a mountain bike adventure, or a day at work that didn’t end with drinks. The perfect cold beer was the reward that solidified the camaraderie after a satisfying adventure or a frenetic après bartending shift slinging beer to the masses. I was pretty good at drinking; I could hold my liquor with dignity while increasing my tolerance, lending me the ability to drink an astounding amount in a single sitting.

After about a decade, I started to consider if I might be drinking too much, though I was in the middle of the pack based on my social observations. Having such alcoholic parents provided a false sense of security, because I knew I would never be as bad as they were. I also had a difficult time finding information that I felt applied to my circumstance. I was a successful professional. I had a beautiful family, a wonderful social circle, and incredible adventures. I was certainly not going to stand up in a room and proclaim myself an alcoholic. Living in a mountain resort town, if I was an alcoholic, then there was an entire population that had to stand up with me. In a 2014 survey by Vancouver Coast Health, Whistler earned the distinction of having the highest rate of binge-drinking in B.C., with 48 per cent of Whistlerites reporting they binge drink one or more times a month, more than double the provincial average.

Binge drinking is defined as five or more drinks in a sitting for men and four or more for women. Four drinks! That is après ski on a Tuesday, with a Baileys coffee, a bloody Caesar and a couple Coronas—and that’s before wine with dinner! To me, these definitions were utterly laughable and easily dismissed. Early on, I went so far as to ask my doctor if they had any recommendations about how much booze was too much and I was offered two options: I could test my liver to see if any damage had already been done, or I could try Antabuse, also known as disulfiram, a drug that blocks the processing of alcohol in the body, making the user feel extremely ill if they have a drink. Again, neither suggestion seemed relevant to my situation, and the status quo continued on for another decade.

Unconscious biases

Like a bad country song, it was personal tragedy that spurred a dedication to drinking: I ran over my old dog. Heartbroken and leaning on what I had come to know as my most comforting companion, I was drinking daily. Never during the workday and never letting it affect my productivity, but when 5 p.m. hit, wine was ever-present. Two decades after moving to the mountains, I knew I wanted to drink less, but was uncertain how to make this a reality. After all, every part of my adult life was unquestioningly saturated in alcohol: celebrations, book club, mourning, adventures, vacations. In fact, other than when I was pregnant or breast feeding, I can’t think of a single adventure or social event I attended where drinks weren’t factored in. Inspired to figure out how to imbibe less when there was an endless stream of compelling events that featured alcohol, I reached out to a friend who had quit drinking despite a long career working in the bar industry. That friend gave me the best advice, which started with a book recommendation.

Annie Grace is the author of This Naked Mind: Control Alcohol, Find Freedom, Discover Happiness, and Change Your Life. The first of many books I read on this topic, it highlighted our spectacularly complex subconscious brain and how it can unknowingly drive our behaviour. When it comes to making any kind of decision, your brain uses a lifetime of experiences it has catalogued to create shortcuts so you’re equipped to quickly make choices. This shortcutting process creates subconscious biases and there are more than 100 types of identified biases that drive behaviour. Personally, I had thousands of experiences that told me booze was an essential part of having fun, relaxing, and socializing. This quick decision-making is amplified by the addictive properties of alcohol and there are very specific biases that contribute to the motivation to both crack that first beer and continue drinking throughout the evening. The physiological effects of the first beer or glass of wine are pleasurable, and range from increased social skills, mild exhilaration, joyousness, relaxation, and even warm tingling down your arms and legs. Unfortunately, these are short-term, and as you continue drinking to extend these great feelings, the physiological response deteriorates into a range of less euphoric feelings, including overly expressed emotions, unwelcome opinions, boisterousness, reduced motor skills, and mood swings. Of course, behaviours can get progressively worse the more drunk one gets, a recipe for some seriously poor decision-making. And no matter how many drinks you have, you will never be able to recreate the same feeling you got from that first sip.

Increased tolerance paired with subconscious bias creates the conditions that cause drinkers like me to continue drinking, even past the point when our conscious mind suggests we stop. Drinking in moderation had long passed as an option by the time I got serious about quitting, and a quote attributed to Irish poet Brendan Behan perfectly sums this up: “One drink is too many for me and a thousand not enough.”

There were many nights, chugging water at 3 a.m., when I would make a firm commitment to myself not to drink that day, which usually only lasted until about 5 p.m. In Adam Grant’s 2021 book Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know, he demonstrates how uncomfortable it is for people to change their minds.

“Questioning ourselves makes the world more unpredictable. It requires us to admit that the facts may have changed, that what was once right may now be wrong. Reconsidering something we believe deeply can threaten our identities, making it feel as if we’re losing a part of ourselves,” he writes.

This discomfort causes cognitive dissonance, which exists when our actions don’t match our mental commitments, creating a sense of psychological disturbance, however mild and imperceptible to our conscious mind, and can lead to a stronger urge to pick up a drink to calm this underlying stress. Ultimately, it’s a self-perpetuating cycle. Despite being inherently untrue, believing wholeheartedly that I needed a drink just to have fun at a party drove me to keep pouring. When experiencing cognitive dissonance, you will work hard to justify your actions (I’m having a drink) that contradict your beliefs (I should quit drinking) and employ strategies to reduce the dissonance your brain is experiencing through justification and rewarding behaviours (drinking more).

Of course, these subconscious biases aren’t easy to overcome and are commonly reinforced by public messaging and social norms. For example, up until late 2019, Health Canada’s webpage on problematic alcohol use stated, “while a small amount of alcohol may provide health benefits for some, drinking excessively can cause serious health issues.”

Getting the monkey off my back

When looking for resources on drinking less, this conflicting messaging only served to reinforce the stereotype that you are the problem rather than the addictive substance you have been conditioned to see as an essential component of your life. The idea that low to moderate amounts of alcohol has health benefits has been widely debunked by science, and yet the message is still amplified by both drinkers and lobby groups. Many studies have emerged over the last decade that highlight the significant health problems that stem from drinking even small amounts of alcohol, including damage to cardiovascular, brain, and digestive health and increased risk for a number of cancers, not to mention the array of social harms associated with alcohol use.

“The risk of negative outcomes begins to increase with any consumption, and with more than two standard drinks, most individuals will have an increased risk of injuries or other problems,” read a report published last year by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction following two years of research and a review of more than 5,000 peer-reviewed studies.

These new studies prompted Health Canada to revise its low-risk alcohol intake guidelines in 2021, reducing the maximum recommended intake from 10 to two drinks per week.

Of course, we are also constantly bombarded by pro-alcohol messaging on social media, in traditional media, advertisements, entertainment, and through observing the behaviour of others in our peer group. It is hard to get away from the idea that drinking is a great idea for all situations. For me, watching for these cues became essential because they worked to counter the new notions I was developing about the true impact of booze. When I reflect honestly, I know a celebration with friends is not fun because of the liquor, but because of my great friends.

I truly loved drinking for a very long time, and it was woven so tightly into the fabric of my social life. It’s been personally rewarding to build awareness of the biases that were shaping my behaviour and relationship to booze. As Carl Jung famously said, “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” This journey to understand my own mental models related to booze has also permeated the way I think about all things, including family, work, motivation, and friendships. I am continually building new and positive biases that confirm life is so much better without alcohol, and that really does include all those things I thought I could never experience without a drink—nice dinners, epic adventures, exotic vacations, stressful and tragic situations.

Someone asked me recently if I still wish I could have a drink. It’s been almost four years since I’ve had one, and I honestly feel so fortunate that I never have to drink again. I sleep so well. I think so clearly. I am a better parent, friend, and partner, and I have been able to accomplish so much more in that short time than I would have had I still been drinking. My bar industry mentor recently experienced significant personal tragedy that for some would have been met with a bottle in hand. When I checked in with them, they said, “Thank goodness I don’t have that monkey on my back.” Like my friend, I can’t ever see a reason that alcohol would be required to make any event better or as a coping mechanism. Admittedly, I may not win a lip-sync battle again, but the conversations and human interactions I have with people now are so much more genuine and memorable. It was hard to write this story for such a public audience, but I wanted to share it as we enter a new year filled with opportunities to make small changes with big rewards. You don’t have to stop drinking to start to consider your own relationship with alcohol in a meaningful way. With any luck, starting that journey will lead to positive changes down the road.

If you are struggling with alcohol use, find more information by calling B.C.’s Alcohol and Drug Information Referral Service at 1-800-663-1441, or search for resources at bc211.ca