Once a year every April, Whistler transitions from being just a ski town for a weekend and is instead transformed into a musical refuge.

During the Con Brio Festival, hundreds of students from all over the province and beyond pack the cobblestones in their dress black, lugging around backpacks and unwieldy instruments as they hustle their way through a hectic schedule of workshops and concerts. These teenagers clamber off school buses to fill the hotels, the sidewalks, the local shops, and the concert halls. They practice their harmonies in the alleyways, jam out in community spaces and go over their notes in restaurants and cafés. For that quick, four-day window, this little Canadian ski town is suddenly filled to the brim with beautiful music.

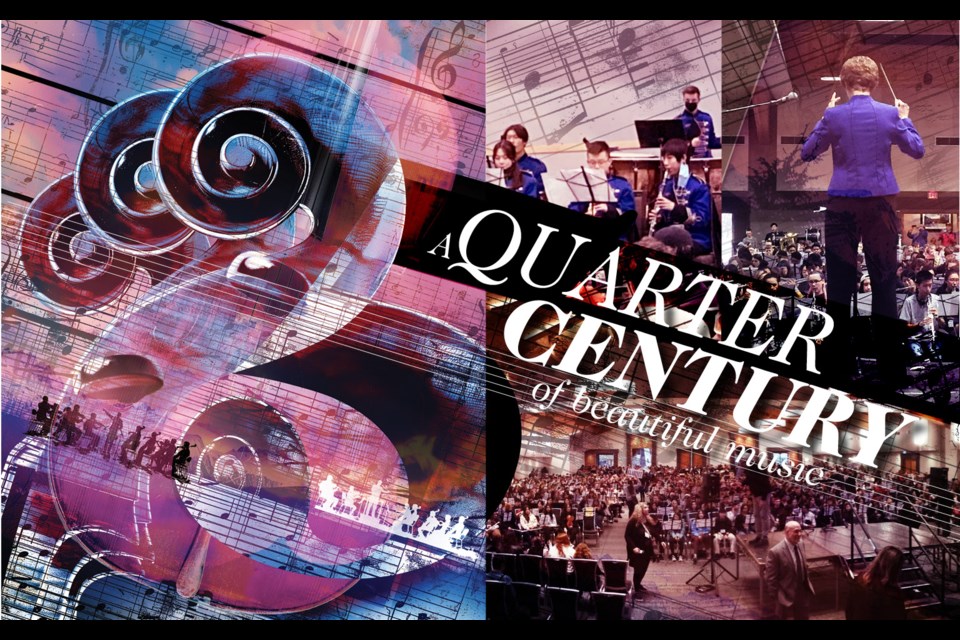

Now celebrating its 25th anniversary, the festival has evolved into a multi-generational tradition. There are former attendees returning as music teachers, parents or chaperones to shepherd the next generation through the Con Brio experience. Since 1999, more than 50,000 musicians have enjoyed the opportunity not only to take in world-class performances and learn from faculty passionate about music education, but to actually perform before an audience themselves.

One of the festival’s promises is that no student will ever play to an empty room.

Careful what you wish for

This story begins 25 years ago, with a West Vancouver band leader named Douglas Macaulay, and the mother of one of his student musicians, Susan Magnan.

It was 1999, and the pair was growing disenchanted with the festival circuit. As they bused back and forth across the province with their student musicians, seeing their charges unengaged and bored, they found themselves coming back to the same question—“could we do it better?”

“Doug and I had travelled to various music festivals together, and as one tends to do, you find yourself thinking, ‘oh, I like that,’ or, ‘I wish they did that differently.’ Well, perhaps you should be careful what you wish for, because now over the course of our festival we regularly fill 700 rooms for the three nights, so 2,100 room nights,” Magnan tells Pique.

Those are the sort of numbers she could only dream of when she and Macaulay first decided to team up all those years ago. As they began to hash things out, outlining their various ambitions for a superior sort of festival, they learned their visions aligned in crucial ways. Keeping everything strictly punctual, that was important, as was keeping the participants active and engaged.

The pair wanted to offer an experience akin to camp, immersive and community-oriented—and ultimately decided Whistler offered the perfect environment to make that a reality.

“I’m not sure we had expectations when we started. We just had the desire to create a legacy, and a desire to offer something in the music festival environment we thought was missing at the time,” says Magnan.

With a lifetime of experience as a choral singer, orchestra member and music PAC president in both school and community organizations, Magnan lived and breathed music. Meanwhile, Macaulay, who would later receive the BC Music Educators’ Distinguished Service Award, had an uncompromising vision about the importance of quality music education. It was this attitude that made them a match, and drove them to create Con Brio.

According to Macaulay, Con Brio offers the sort of experience that impacts the students’ entire life, creating irreplaceable memories and countless relationships. From the chaperones to the teachers to the musicians, they’re all working together to create the perfect musical environment.

“I always remind kids at the festival that this is not their teacher’s job. They don’t have to do this, give up their whole weekend to come here,” he says.

“But they do it because they believe in music education and their students.”

Music from our ancestors

When Con Brio organizers were looking for faculty to inspire their students during the first year of the festival, Macaulay reached out to gospel singer Marcus Mosely—who would go on to be inducted into the BC Entertainment Hall of Fame in 2016. He was a member of the gospel trio The Sojourners, had starred in numerous musicals, and even provided a singing voice for a character in My Little Pony.

But Mosely’s real passion was introducing student musicians to the protest music of the civil rights era, and showing them how gospel has the power to create seismic cultural change. That’s why he has participated as an instructor at nearly every Con Brio Festival since it started.

“I used to work in the cotton fields of Texas with my mother when I was a kid, and what I remember most clearly is that there was always a gospel song under her breath. I would hear her singing, and I loved it, and what I learned later on was that she was grounding herself, keeping herself with her spiritual centre, amidst an oppressive culture,” he tells Pique.

“That music helped my ancestors, and it helped my mother to find strength and courage in the midst of struggle and hard times, and gospel music has had that power in my life. Many kids have never heard these things before, so I act as a living witness to the significance of music over history.”

Though the various instructors at the festival follow different musical traditions, Mosely believes they all have the same driving impetus—to create a better world by fostering the next generation of musical talent.

“When I share gospel music, I’m not sharing from a religious point of view or trying to convert anyone. It’s a message of universal empathy and compassion, and it’s about all those things we have in common. It’s historic, cultural for me. For me it was about the civil rights era, and how we would sing before going to fight for the right to vote or march for freedom,” he says.

“And they get it. I try to apply whatever issue is relevant to them, whether it’s caring for the planet or caring for each other. I want them to be free to express themselves.”

That’s what the organizers wanted as well. When Macaulay first walked the corridors of the venue and strategized the best way to approach the programming, he knew they wanted to minimize the time students spend stationary and maximize the time they spend active, engaged and performing.

“When we were coming up with the name Con Brio, which means ‘with spirit,’ we knew we wanted something that reflects the animated nature of what we wanted to do here,” Macaulay says.

“We’re a festival of active learning through participation. So no sitting, no getting lectured to, we want everything to be in motion, to push the tempo a bit and create urgency.”

Mosely says it is that energy that has kept him involved over the years.

“I live in Vancouver, and every now and then I’ll run into kids at Starbucks who are now graduated, maybe adults, and some of them have gone into music or music is part of their lives, and they’ll say, ‘I remember you from Con Brio,’ and I get to find out what they’re doing with their lives. Many have chosen a career in music,” he says.

“It makes me feel great. I want to share a level of joy, but also teach compassion, empathy and social justice for everyone. To give that message to thousands of kids in a musical context, it feels like you’re making an impact on the world because they go everywhere. They grow up and go out into the world with that influence.”

A 25-year learning curve

Sometimes you have the best intentions, but the world just gets in the way.

That’s what Con Brio organizers learned following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, when a number of music festivals were axed due to international travel constraints. Multiple American schools had already booked their festival spots, and had to cancel at the last minute.

“We looked around us. All the other festivals were cancelling. We took a deep breath and decided to continue. We were one of the few that kept going, and I’m glad we did,” says Magnan.

“It was quite a scramble, and we ended up being a very local festival, but it all worked out.”

The next trial came with the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the festival being cancelled in 2020 and being offered online the following year. Organizers remember this as a time of uncertainty and innovation, as they tried to manoeuvre the changing landscape. The festival was held in-person again in 2022, but didn’t open its registration to full capacity again until 2023.

“We just don’t give up. We’re not profit-motivated. We’re motivated by educational value and the music. So we don’t care if we make money, we want to run a festival and we’re happy if we don’t have to write a personal cheque to cover the expenses,”

says Macaulay.

He is amazed to see how the demographics have shifted over the years. They now have triple the number of schools attending as they did in 1999, with a growing number from the U.S., which means they regularly max out their 3,000-participant capacity. This year they’re particularly thrilled to welcome 120 students from Hawaii.

“Because these kids come from all kinds of different places, they have different responses to even being in the village. One year we had students from Alabama and they were blown away. One student said to me, ‘I had no idea the world was like this,’” he says.

“Every year there’s a moment, or maybe a couple of moments, where you think, ‘wow, this is why we’re doing this.’ It can be quite life-changing for kids, because it might even be their first time away from home.”

A quarter century in, the organizers are still fine-tuning their approach and programming. The resulting experience is as different as each student who takes the stage, according to Magnan.

“Each and every year I am so impressed by the young people who come to perform. I’m moved to tears almost every time, not only by the performances but also by how music is a real way to build cooperation,” she says.

“It’s not like a sport, where you have someone doing a breakaway to get a goal. With music you all have to play your part and rely on each other, and it fosters that in young people so that they become polite and caring and cooperative.”

Where the spirit is

All music is an expression of life, which is why Con Brio has taken a multicultural approach to choosing its faculty and music over the years.

More recently, organizers have made Indigenous inclusion a priority, taking on a cultural advisor and introducing a welcome song. This year, elder Bob Baker, whose music was featured in the 2010 Olympics, will share with students. According to Macaulay, who first met Baker at a band concert in West Vancouver, the Squamish Nation performer makes a powerful impression.

“It’s wonderful music with a different structure, imagined in a different way, that we translate using Western orchestra band instruments. The main thing is the opportunity for tangible engagement, because for all those kids who participate it will change their thinking of First Nations people and their culture,” he says.

“It’s different to learn in school rather than engaging in person. When you have someone up front sing a song for you and ask you to play it back, that’s a whole other level. It engages the students in a different way.”

Baker says the music will come with cultural lessons.

“We’re going to share how it is that songs are received, the spirit of a song. There’s a bit of an explanation that goes before the song, that’s part of our teachings, and we always address what the song represents,” he says.

His work centres around the spirit of the animal kingdom, and the teachings of coastal

Indigenous populations.

“A lot of what I’ve been sharing is trying to get across the sense of where we are on the West Coast. Our nations have been here for thousands of years, and we’ve developed cultures—a canoe culture, a longhouse culture, a musical culture—and the spirit of the nation is family, so we conduct business as a nation in that spirit,” Baker says.

“I want to remind everyone how we should be looking at where we live and appreciate the wealth of everything we have. The trees, the mountains, the lakes and rivers and oceans. We have killer whales, grizzly bears, everything here. We get caught up in whatever trivial thing gets magnified, but we should always remind ourselves where we are living and the beauty of the West Coast.”

Baker likes how Con Brio has progressed in recent years as it embraces diversity.

“I’d love to see how it’s going to evolve creatively, and what they come up with as a way to create an overall experience for everyone to share,” he says. “It’s a pretty big calling.”

A festival of choice

After 25 successful years, Con Brio’s organizers are feeling pretty good about the reputation they’ve established and the space they fill in the country’s musical landscape.

“People vote with their feet,” says Magnan. “They choose which festival they want to go to, and we’re only as good as our reputation. I feel quite proud that we’ve maintained our standards and that we’re a festival of choice that sells out every year.”

This all comes during an era when many music departments aren’t being prioritized or funded like they used to, and Macaulay says they understand how indebted they are to the music teachers who take the time to bring their students up the Sea to Sky.

“It’s tough to give a generalization, because it’s different from district to district how they support the arts. Music teachers quite often have to battle for their programs, and they’re largely successful. That success is based on the drive and passion and work ethic of individual teachers. They have to lead the charge,” he says.

Towards the end of the weekend, students are invited to attend a professionally staged gala concert designed to introduce students to “music they didn’t know they’d always loved,” with a range of instrumental and vocal performances across culture, genre and style.

But the true highlight each year is when the students gather for the mass choir and mass band events, which feature 400 singers and two groups of 700 musicians performing a First Nations piece in unison. It’s the culmination of all the learning and cooperation that has occurred over the weekend, bringing everyone together for a common artistic purpose. The result can be overwhelming.

According to Magnan, it’s a stirring finale to take in.

“If you put your hands on the wall of the ballroom in the conference center, you can actually feel it vibrate with the force of the music,” she says.

“It’s a truly extraordinary thing.”