At just after 7 a.m., I get a call from the trip leader.

"How much room do you have in your tent?" asks Heather Filyk, explaining how she and the rest of the group are en route to Joffre Lakes Provincial Park, where we will be spending the night.

I sit up in bed, trying to sound peppy. "It fits three!"

In reality, I'm not sure. Because the tent, in fact, isn't mine — I borrowed it from my editor. This whole thing — backcountry camping — is new to me.

Motorhomes and car camping: I'd done that. Lugging food and shelter into the wilderness? Not so much.

When I meet the group, that much is obvious. With a rolled-up air mattress in one hand and a tent the other, they look at me aghast — like, seriously?

One of the guys, a bearded uni student with plenty of backcountry experience, offers to help. Laying the mattress on ground, he methodically re-rolls it, ridding it of excess air.

Then he grabs some straps out of the back of a car and fastens everything to my pack. "These always come in handy," he says.

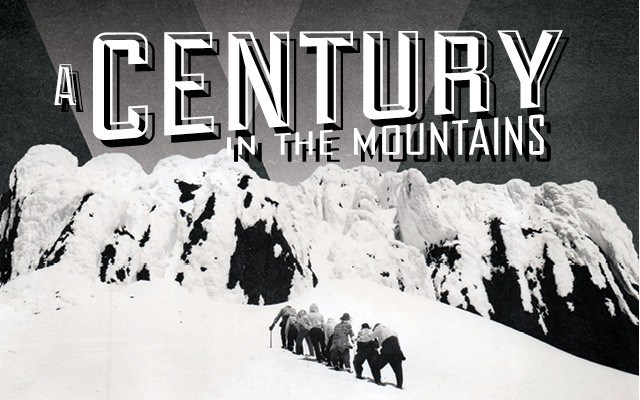

The group is part of the University of British Columbia's Varsity Outdoor Club (VOC), a student-led organization that turns 100 this year. Made up of current students, alumni, and non-UBC affiliated outdoor enthusiasts, the VOC has served as an important incubator for some of B.C.'s most prolific explorers, some of whom have played a vital role in Whistler's development.

Built on an instruction model where members teach other members (for free), the VOC has also enabled thousands of people with little experience — that is, people like me — to explore B.C.'s backcountry.

The hike up takes a few hours. And apart from sore feet (note to self: don't wear skate shoes while hiking), it's fun. The views in particular — the way the clouds float over the trees and gently blow across the mountainside — are breathtaking.

As we ascend, Filyk — an ebullient 24-year-old wearing a purple sleeveless top and purple pants tucked into wool socks — checks in with us constantly: making sure we aren't moving too quickly, explaining the importance of keeping on the path rather than trampling over the plant life beside it.

In the past few years, Joffre Lakes has emerged as a social-media darling, leading thousands of people — with differing levels of experience and respect for the backcountry — to make the trip from the Lower Mainland and beyond.

According to BC Parks, it has seen tremendous growth in visitation within the last five years, and in the 2016-17 season has already accumulated 100,000 visitors. Staff routinely haul bags of trash out of the park and there have been calls to severely limit access to it.

I watch as well-dressed city folk with impossibly clean shoes venture onto the notorious "selfie log," a fallen tree that extends from the shore onto Middle Lake, allowing people to capture "the perfect shot."

Manipulating their bodies like celebrities on a red carpet, they attempt to fit the Holy Trinity of the lake's beauty into the frame — its unbelievably blue waters, the stream that feeds it, and the towering mountains that surround it.

Whistler: The early days

Sitting on the Marketplace Tim Hortons patio, Karl Ricker — a former VOC president — explains the outsized role the club has played in making Whistler an internationally recognized destination for outdoor adventure.

A no-nonsense type with an encyclopedic knowledge of the history of the club, he looks like he's just returned from the bush. Wearing a worn-out black vest, his black horn-rimed glasses contrast with his wild mane of white hair. Clear tape, used as a makeshift bandage, covers one hand.

In mountaineering circles, Ricker is best known for conquering the Spearhead Traverse, an iconic alpine route that connects Whistler and Blackcomb Mountains. Along with a group of three other VOC members, Ricker was the first person to complete the trip in 1964.

Explaining why he wanted to do it, Ricker, who seems allergic to pretense, is matter of fact: He'd done a similar traverse in Austria, and thought, "'Well, let's see if this one is as good as that one.'"

Over the years, the Spearhead Traverse has grown popular, with Arcteryx-clad athletes in high-end touring gear regularly completing it inside of a day. (The Spearhead Huts Society is currently in the process of building a series of state-of-the-art huts along the 40-kilometre route — something Ricker first envisaged long ago.)

By today's standards, the equipment Ricker used was pre-historic: Heavy metal skis, packs brimming with food and thick ropes, and a map that "wasn't bad — a bit vague in some places."

Ricker's group took nine days to complete the trip, one day less than they had budgeted for. Self-described "peak baggers," they climbed 17 peaks and ridges along the way.

This, of course, was well before satellite phones, and rapid-response search-and-rescue teams. "You didn't worry about it," says Ricker, when asked about the risks. "The biggest fear was breaking your leg in those days. A broken leg is a real pain in the ass."

In an entry that appeared in the 1964 VOC journal, Bert Port documented the trip, noting where the group found the best skiing and where the map needed to be amended. The weather wasn't great, but the group had a blast. "All in all, this is a fine touring area," concluded Port. "It deserves more attention than it has had in the past."

For Ricker, the trip spoke to the awesome potential of the area. "We felt like we'd found another circuit like I had seen in Austria," he says between sips of coffee. "And we knew it was going to be popular over time. The secret was to get the lifts built on the mountains, to get the trip started."

If you build it, they will come

During the traverse, Ricker was contemplating a big decision.

A group of forward-thinking businessmen wanted to build a ski resort on Whistler Mountain, and they'd come to the VOC with an offer: Free land, as long as you come and build a cabin. For Ricker and other VOC executives, it was tempting.

Since the late 1940s, the VOC had organized two-week "pilgrimages" to nearby Garibaldi Provincial Park. They already knew the area held something special.

After some deliberation, the VOC decided to take the offer. As project manager for the build, Ricker led a team of students and alumni in an incredible feat of cooperation and self-reliance.

Forming a chain, workers moved materials half a kilometre by hand, and within four months, they had built the Whistler Cabin, an impressive building with a massive fireplace and an "indestructible dance floor" that still stands proudly, just off Nordic Drive.

Excess manpower was dispatched to explore and build trails in the area that are still popular today, including the Cheakamus Lake and Singing Pass trails.

The only hiccup, says Ricker, was that it "turned out the government knew nothing about the club cabin area."The Garibaldi Development Association — which had given the club the go-ahead — didn't have the right to assign the land.

Thanks to some help from John Macdonald, an understanding UBC president with government connections, they were able to sort it out. "We started pouring cement before the government gave us the final go-ahead," says Ricker, breaking into a mischievous smile.

Now 81, Ricker continues to explore and enjoy nature with a group of former VOC members. Bonded together by the extraordinary adventures they've had the privilege of experiencing, they take annual ski and hiking trips.

"Once you're in the VOC, you're in for life," says Ricker. "The activities breed (camaraderie) naturally. Once you enter the mountain fraternity, you're sucked in it for life."

Scrambling

We set up camp at the last of the three Joffre Lakes, Upper Lake, an oval body of water that looks like an infinity pool from where we stand, dropping off into the valley below.

Katie, a recent UBC graduate, helps me set up. An experienced camper, she clears the site of debris and orients the entrance of the tent towards the water.

Then, at Filyk's suggestion, we go "scrambling," VOC-speak for hiking on sketchy rocks. Using a GPS device, Filyk guides us up a field of boulders the size of beach balls. Beneath us, water flows.

Jumping from boulder to boulder, I start to get the appeal. I feel free, thrilled to be exploring a last vestige of the natural world with a group of kind, likeminded people.

Around 45 minutes in, it starts raining. Filyk worries that the boulders — many of which have a thick layer of lichen on them — will become slippery, so we turn back.

On the descent, Filyk — who moves quickly — talks about her induction into the VOC fraternity.

From Ontario originally, she joined the club two years ago when she began a graduate degree in microbiology and immunology at UBC. She quickly graduated "from park camping, to backcountry camping, to ski touring, and then mountaineering."

Through the VOC, she's met a bunch of similar-minded friends who are always willing to show her the way. "Everyone is so wiling to help you. It made the transition super easy," says Filyk.

She loves the outdoors, and now she's teaching others what she's learned. Backcountry camping is good for the soul, she says. "There's no one hassling you to buy something, no advertisements anywhere. You just get to be."

Back to the mountains

The VOC eventually lost its cabin in Whistler.

It ended up forming a rift in the club. While some welcomed the changing face of Whistler — from a small hippy ski town to a major internationally recognized resort — others felt that it was out of line with the original spirit of the club, which revolved around exploring uncharted places. Plus it was expensive, a major drain on VOC finances.

In the 1970s, the Whistler-loving skiers split to form their own group, the VOC Ski Club. The club eventually tried to buy out the VOC, but the sale was blocked by the UBC Alma Mater Society (AMS), a student group that had put up the original funds for the cabin.

The AMS, however, was eventually forced to repay the VOC for the costs it incurred building the cabin. The $30,000 was used to build a hut on the edge of the Pemberton Icefield, and rebuild a hut on Brew Lake, not far from Whistler.

This history is documented in A Century of Antics, Epics & Escapades: The Varsity Outdoor Club 1917-2017, a soon to be released coffee-table-style book in honour of the club's centennial. Elliot Skierszkan, a PhD student who has been with the club for several years, led the project. The VOC, says Skierszkan, has truly "punched above its weight" when it comes to mountaineering. They've bagged numerous first ascents; there's even a mountain named after them — Veeocee Mountain, located at the northeast end of Garibaldi Provincial Park.

VOCers have also helped popularize B.C's backcountry, explains Skierszkan. In 1967, Glen Woodsworth wrote the first rock-climbing guide to Squamish, and in 1982 John Baldwin wrote Exploring the Coast Mountains on Skis, a ski-touring book that is now in its third edition. "(Baldwin) wrote the book on how to ski-tour in our part of the world," says Skierszkan.

That said, the history isn't all rosy. In its early days, there were different sets of rules for women and men, and club presidents were always men. Club trips were segregated, with rules precluding men and women from sleeping under the same roof (or tent).

The club has come a long ways, explains Skierszkan, pointing out that, since 2000, four out of seven VOC presidents have been women.

Skierszkan thinks the nature of mountaineering helps breed equality. "The usual social norms don't apply in the backcountry, and that probably helped to a certain degree," he says.

Other major club accomplishments include members who went on to start the outdoor recreation retailer Mountain Equipment Co-op, and others who played an instrumental role in developing Squamish as a climbing mecca.

Boiling 100 years down into one sentence, Skierszkan describes the history of the VOC as the story of "a bunch of students with no money, who put themselves out there and really accomplished a lot."

Not all fun and games

Standing next to the playground in Whistler Village on a busy Saturday, VOC alumnus Vance Culbert tells me what he really thinks about the resort. "The function of places like this is to keep crowds away from the bush," he says, cracking a smile as his daughter vaults through the obstacles with preternatural speed.

In 2001, Vance ski-toured from Vancouver to Alaska with a group of three friends. Along the 2,000-km trek — which involved six months of planning — the group dealt with severe snowstorms and avalanche danger; one member of the group nearly lost his life after breaking his neck skiing down a logging road.

It was, Vance explains, a life-affirming journey through an area of incredible beauty that few ever see. "I'd do it again," he says.

It is, perhaps, fitting that Vance — the son of legendary mountaineer Dick Culbert — would undertake such an epic trip. In the 1960s and '70s, Dick, who has been called the greatest Canadian mountaineer of his generation, played an instrumental role in exploring and charting the Coast Mountains.

Dick racked up hundreds of first ascents, and published A Climber's Guide to the Coastal Ranges of British Columbia in 1965, the first guidebook of its kind for the region. Published shortly after he graduated from UBC — where he also served as VOC president — the book was informed by his many adventures with the club.

Like others I spoke to, Vance — who has the muscular build of a rock climber and the crow's feet of a guy who's spent his fair share of time in the alpine — says that finding the VOC changed his life. The activities, he explains, were "totally addictive," and led to lifelong friendships.

And what exactly did he learn? "Resistance to pain, resistance to suffering, learning how to go through something that's not that much fun and then later pretend it's fun," Vance says in jest. (Skills, one assumes, that serve him well in his current work running relief programs in conflict zones, including Syria and Iraq.)

And while he is evangelical about his experience with the club, Vance is also critical of some of its ways. During our conversation, he loops back to the issue of safety several times, grappling with whether the club's instruction model — which involves members, not professionals, teaching critical backcountry skills to other members — is sound.

For Vance, safety in the mountains isn't some abstract thing. Two years after the Alaska trip, two of the members of his original party — Guy Edwards and John Millar — lost their lives climbing a technical route up Devils Thumb, a 2,767-metre mountain straddling the Alaska-B.C. border.

Vance, Edwards, and Millar all met through the VOC. They had climbed the mountain as part of their trip.

At one point, I ask Vance how many of his friends have died in the mountains. He lets out a long sigh, followed by an even longer pause. "I've lost so many people," he says, not wanting to count.

Mountaineering in B.C., he explains, has always been guided by a do-it-yourself ethos. Even in nearby Washington and Alberta, things tend to be stricter, he says.

And in Europe — where he now lives — it's a whole different ballgame. "People with a similar level to me, would never dream of going into the mountains without a guide," he says.

Recently, Vance was doing a solo climb up the Matterhorn, the jewel of the Alps, when he tried to sidestep a group that was holding him up. The group's guide bodychecked him. The message the guide was trying to impart? You shouldn't be here alone.

"It's just what you do — you hire a guide," says Vance. "If you're rich, it's probably safer."

In 100 years, only two people have died on official VOC trips. But according to the organization's website — where they keep track of serious injuries and deaths and try to draw safety lessons from them — 11 "VOC-related" people, meaning members or former members, have died in the mountains, with falls and avalanches being the principal causes.

In January 2015, two active VOC members lost their lives in Joffre Lakes Provincial Park. Stephanie Grothe, a 30-year-old German PhD student who had served as president of the VOC the year prior, and Neil Mackenzie, a 31-year-old post-doctoral fellow from Scotland, were climbing Mount Joffre's Central Couloir — a blood-curdling, steep channel of ice and snow that's flanked by massive rocks on either side — when something went horribly wrong.

Grothe, Mackenzie, and another non-VOC related climber, Elena Cernicka, were tied together with rope; they fell some 600 metres.

In an interview with Pique, club president Nick Hindley underlines that the deaths did not happen on an official club trip. He acknowledges, though, that the stakes in the backcountry are always high. "There is an inherent risk in what we're doing," he explains. "We put a strong emphasis on that."

Hindley notes that the club does have curriculum for new mountaineers and that members build up their skillset over time. Trips are categorized by ability level and vetting is done to ensure people don't go on trips that are beyond their experience.

But when asked if teaching should be restricted to professional guides, Hindley says he doesn't want to see the VOC move in that direction. "(The VOC) is (about) friends sharing skills. That's my favourite thing about the club," he explains.

The club, he says, is upfront about the risks involved. "We definitely clarify that we are not guides, that we are likeminded individuals who want to share knowledge and share an experience with someone."

At the end of our conversation, Vance comes to a similar conclusion. "As soon as you bring in certified guides, you can't do the kind of things they are doing today," he says. You can't "throw someone" into a crevasse and then practice rescuing them.

"I'm not sure if the VOC way of learning is any riskier," he adds, noting that mountaineering accidents are common in Europe as well. "It's a dangerous sport."

Like Hindley, Vance sees the organic way knowledge flows from one VOC member to the next as a fundamental appeal of the club, a holdover from an era when people like his dad would just get out there and explore.

He doesn't want to see it change. "I'm actually amazed that the VOC is able to get away with what it does," he tells me. "I don't know if it can stay like that — in the world we live in."

Totally enthralled

On Day 2, we get up before sunrise. We chill for an hour or so, looking out at the steep slopes and ridges that surround the campsite, forming a horseshoe of towering rock.

A massive glacier sits atop the far end. Water flows from it, cascading over a series of small cliffs and ending in a full-on waterfall.

The sun hides behind the ridge opposite us. And then, like an explosion, the sun emerges, filling our campsite with blinding light.

On the hike down, I chat with Trevor Marsden. An athletic electrician who used to play paintball professionally, he reminds me of guys I grew up with. Like me, this is his first backcountry camping trip — and he loves it.

When I ask him why — what he gets out of it — he likens the experience to the first time he exited an isolation tank. Designed to cause extreme sensory deprivation, users float in total silence and darkness in water that is heated to body temperature.

The experience, which is often called "floatation therapy," can lead to intense introspection and even hallucinations.

"When you come out of a float tank, you are enthralled in your own consciousness," Marsden tells me. "What I feel now is like that moment. It's killer, man."