A study tracking wildlife across 92 square kilometres of northern British Columbia has found wolf culls might not be the best solution for saving declining caribou herds.

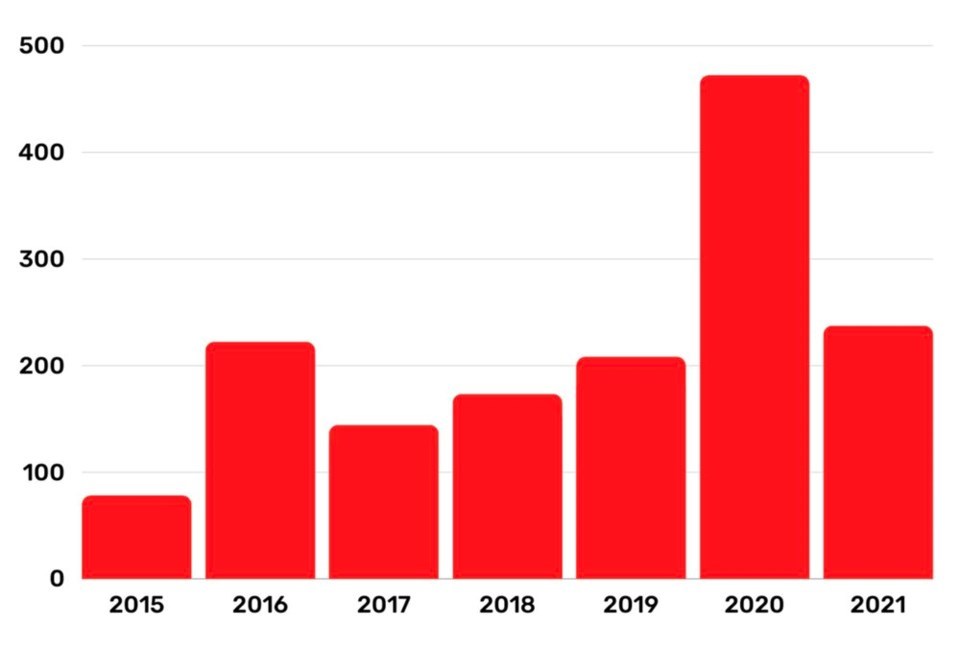

Since 2015, the province has responded to threatened caribou populations with an annual, and controversial, wolf cull, killing 472 wolves in 2020 alone. Over the last six years, 1,447 wolves have been put down, according to data provided by the provincial government. A 2019 report from the province found the culls “will have to take place until habitat restoration and protection overcome the legacy of habitat loss.”

But new research funded by the British Columbia Oil and Gas Research and Innovation Society is offering another path forward.

The study, published earlier this month in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, was conducted across a swathe of territory outside Fort Nelson, known as the Parker Caribou Range.

Lead author Jonah Keim, an independent biologist and data analyst, says his team deployed 100 wildlife cameras for nearly three years to track prey and predator behaviour. The researchers discovered predators took advantage of human-made changes to the landscape, travelling along gas and oil cutlines or trap lines in the forest to access threatened caribou herds.

Jonah Keim's study found 'wolf moguls,' as well as hinged and downed trees prevented wolf-caribou encounters by 85%. By Jonah Keim

Jonah Keim's study found 'wolf moguls,' as well as hinged and downed trees prevented wolf-caribou encounters by 85%. By Jonah KeimKeim and his team obstructed those paths, hinging or downing trees along the man-made trails or piling earth up to mimic natural hummocks — what he describes as “wolf moguls” — in wetlands where many caribou forage.

“When you look at caribou conservation, it’s pretty well recognized that the leading drive between conservation problems is habitat loss,” Keim tells Glacier Media. “But we started realizing caribou and wolves were very specific about the habitat they use.”

The researchers saw an immediate response.

Where barriers were erected, wolf-caribou interactions declined 85%, and black bear-caribou encounters dropped by 60%.

In the same way public health has worked to drive down COVID-19 transmission by limiting interactions between people, Keim says keeping wolves and caribou apart could save the lives of countless animals.

“If you can manage the encounters, you can manage the [number of] caribou killed,” he says.

2020 was the deadliest year for B.C. wolves killed under the province's cull program. Of the 1,447 wolves killed since 2015, 472 were killed in 2020 and, so far, 237 have been killed in 2021. Infographic by Glacier Media, with data from the Province of B.C.

2020 was the deadliest year for B.C. wolves killed under the province's cull program. Of the 1,447 wolves killed since 2015, 472 were killed in 2020 and, so far, 237 have been killed in 2021. Infographic by Glacier Media, with data from the Province of B.C.NO ALTERNATIVE STRATEGY

Keim says the province’s wolf-cull strategy is based on the premise that removing wolves will give caribou habitat a chance to recover.

“’We’re going to go kill wolves and hopefully this will buy us time to restore the ecosystem’ has been the argument,” he says. “But boreal forest is fairly low-productivity. It takes time to recover... It can take decades to grow back trees.”

He adds culling wolves could have unforeseen consequences on moose and deer, two species the predator hunts in other parts of its range. Those two animal populations could get out of control if too many wolves are culled.

“It’s kind of a short-term solution. But it’s not dealing with the actual cause,” says Keim.

“There has been no alternative strategy.”

A woodland caribou captured by one of Jonah Keim's 100 wildlife cameras. His team tracked predator-prey encounters over two-and-a-half years. By Jonah Keim

A woodland caribou captured by one of Jonah Keim's 100 wildlife cameras. His team tracked predator-prey encounters over two-and-a-half years. By Jonah KeimA HUMAN PROBLEM

Trappers and oil exploration teams aren’t the only humans making a predator’s path to caribou easier.

Keim’s research found ATV trails helped blaze corridors for wolves to come out of the highlands and hunt caribou. In the winter, they documented how snowmobilers would tamp down the snow, allowing predators to more easily move along winter trails and access prey.

The findings suggest that habitat loss is not always about the destruction of an entire ecosystem. Even small alterations on a landscape can tip the balance in favour of one species.

“People were not thinking this way,” he says. “These are small features on the landscape.”

“It’s not about the footprint; it’s about the foot.”

A NEW CONSERVATION PLAYBOOK?

Humans continuing to blaze trails through caribou territory could stand in the way of scaling up the kind of predator barriers Keim and his team erected.

But ATV and snowmobile trails could also offer a release valve by opening up predator corridors to areas not frequented by threatened woodland caribou.

The study is built on a decade of research about predator-prey dynamics surrounding woodland caribou and people in northern B.C. and Alberta. Over that time, Keim says his team has collected over 750,000 motion-triggered photographs, or 400 years' worth of surveillance and monitoring data on wildlife and people.

“What we’ve done is provide a playbook how to do it,” says Keim. “Now that we’ve shown how to do it, why not try?”

The province is not so sure.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development questioned the study’s methods, writing in an email to Glacier Media: “The statement that they reduced the encounter rate between wolves and caribou by 85% could be misleading, really they can only say that fewer caribou and wolves walked past the cameras.”

A woodland caribou and its young caught by one of Jonah Keim's 100 wildlife traps. Over 750,000 motion-triggered photographs were captured as part of the research. By Jonah Keim

A woodland caribou and its young caught by one of Jonah Keim's 100 wildlife traps. Over 750,000 motion-triggered photographs were captured as part of the research. By Jonah KeimThe province, adds the spokesperson, is already engaged in habitat restoration in caribou corridors; however, blocking wildlife corridors “does not address the risk that is caused by increased number of wolves on the landscape and the resulting immediate threat to caribou.”

The ministry's statement says the potential for Keim’s methods to be used as an alternative to culling wolves is “extremely limited” because of the scale of restoration required to impact the entire caribou population. The spokesperson also cites concerns over the amount of time it would take to implement such measures, its limited application outside of boreal forests and its high cost.

“Wolf reduction offers an option that immediately prevents the continued decline and potential extirpation of caribou herds, allowing time for additional recovery actions such as habitat restoration to become effective,” the email reads.

PROVINCE TAKEN TO COURT OVER CULL

Meanwhile, the environmental group Pacific Wild is set to appear in court July 7 and 8 to challenge the B.C. government's method of killing wolves.

B.C. amended the Wildlife Act in January to allow for wolves to be trapped with a net gun from a helicopter; after they are radio-tagged, the collared wolf returns to its pack, revealing the location of the other wolves, which are then shot by helicopter-borne snipers, according to a court petition from Pacific Wild.

Pacific Wild says the case is about the government's power to allow an aircraft to be used for hunting and the legality of permits issued by the province for the cull.

The petition to the court, filed last July but delayed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, says it wants a judge to quash any permits issued for the wolf cull and to clarify the law as it applies to the killing of a vulnerable wolf population.

None of the claims have been tested in court.

With files from the Canadian Press

Stefan Labbé is a solutions journalist. That means he covers how people are responding to problems linked to climate change — from housing to energy and everything in between. Have a story idea? Get in touch. Email [email protected].