Flood evacuees across the province are in a state of restless anticipation after Environment Canada warned up to 80 millimetres of rainfall could fall across Metro Vancouver and the Fraser Valley starting Wednesday night.

The River Forecast Centre has issued high streamflow advisories for all regions of the coast and the province is warning people to avoid all non-essential road travel. Environment Canada says the storm is expected to be shorter-lived and less intense than last week's atmospheric river event. The agency warned, however, that it will still bring moderate to heavy rain, strong winds, and may worsen recent flooding as well as vulnerable landscapes and infrastructure.

In the Fraser Canyon community of Spences Bridge, widespread flooding and landslides have already knocked Highway 8 into the Nicola River in at least 18 places, according to the province.

Known as Blue Sky Country, Thompson-Nicola Regional District representative Steven Rice says several people had their homes swept away, losing up to 40 acres of land as the Nicola River changed course last week.

When Rice abandoned his home with his wife, Paulette, he posted on Facebook he had lost electricity and was evacuating to town.

“Lights went out at the farm. Paulet and I decided to vacate,” he wrote.

Shortly after, all the phone lines went dead and stayed that way for four days. Since then, Rice and his family have been living in the back of their Spences Bridge restaurant with another family and their five farm dogs.

When four days later, communication was restored, Rice checked his Facebook post.

“I can’t get out of my yard,” wrote his neighbour. “I’m still OK though.”

The woman in her 70s remains missing. Her property washed away, Rice says others have seen pieces of her house float down the Nicola River.

“The last comment on there was from her,” said Rice through tears. “That sentence just still is ingrained.”

Meanwhile, Mounties and locals organized an airlift for dozens of animals stranded by the floods. Those who have lost their homes are staying with friends, in spare cabins or with family.

But the only way out of town is toward Cache Creek, and Rice says he fears the coming rain could lead the hoodoo sand formations — big, naturally occurring towers of sand and gravel — to collapse into the Nicola River and cut off the only route to the outside world.

“We’re readying in ourselves for the worst and it can get worse,” he said. “We're in these little silos of isolation in the canyon and hopes a dead end.”

Still, Rice says they’re keeping their spirits up decorating the restaurant for Christmas, even hosting a Cribbage tournament to bring some sense of normalcy in an abnormal time.

Donations like pellets for peoples’ wood stoves are being handed out at a community centre in town

With a lot of people suffering from grief, one of the big gaps right now, says Rice, is a lack of mental help services.

“We do not need any more rain,” he said. “That rainstorm is a huge concern for everybody right now.”

The storm isn’t the only thing on the evacuees’ minds. Rice said he’s anxious to check on his home to assess the damage and throw a blanket over a huge store of canned and jarred food.

Much of the population’s food supply comes from farming, hunting or fishing, and with the power out and the temperatures dropping, Rice says people will lose everything they’ve saved up for the winter.

“We know we all don't have jobs next year,” he said calling for military government or military helicopters to support the community’s airlift capabilities. “It's a desperate situation.”

FLOODED FARMERS BRACE FOR RAIN

Over 170 kilometres downriver, thousands of residents in Abbotsford’s Sumas Prairie were warned Wednesday their tap water can only be used for flushing toilets.

The city handed down the advisory after contaminated floodwaters entered the municipal water main through uncontrollable breaches.

In a press conference held Nov. 24, Abbotsford Mayor Henry Braun explained floodwaters have pooled in the eastern section of Sumas Prairie; in that same area, there are damaged pipes that transport water through the region. As the water may have toxic substances in it, Braun explained, the water is only useful for flushing toilets.

"There is fertilizer out there, there's fuel tanks, both gasoline and diesel tanks. There's a lot of tractors that are underwater, there's a lot of vehicles underwater," he said. "So all of that is migrating, I'm pretty sure, into the water, which is why we want to make sure that the public doesn't drink that water."

The mayor added that there are 1,200 acres of blueberry crops that have been underwater four or five days. Those plants, he said, have probably died — a serious blow for a crop that takes years to come back.

Some farmers the mayor has spoken with aren't sure they'll be able to afford that investment, he added.

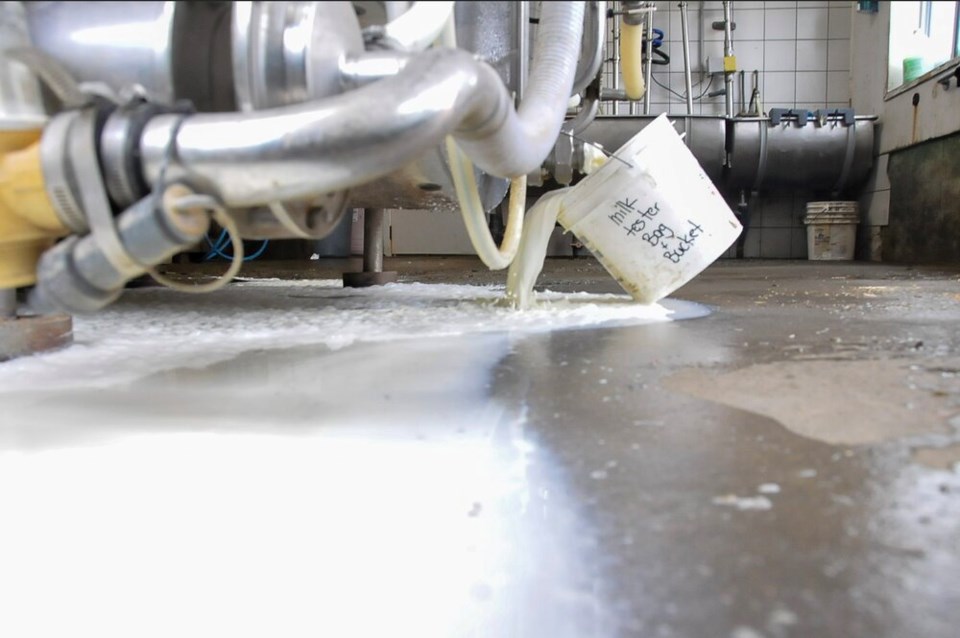

At U & D Meier Dairy, the contaminated water has meant Karl Meier and his twin brother can’t clean their milking equipment. They are now dumping roughly 7,000 litres of milk down the drain every day.

While the farm is covered for those losses, the Meier twins’ evacuated children remain displaced and haven’t been able to return to the farm.

All that’s left are his wife, a few farmhands and their over 240 cows who are just now getting healthy after spending days buried in a metre of floodwater.

Still, Meier counts himself lucky: the BC Milk Association estimates about 500 cattle died in floods across the region. Another 17,000 remain alive in Sumas Prairie. Across the province, farms are managing to get 80 per cent of B.C. dairy supply to market.

Meier said he spoke to Minister of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries Lana Popham Tuesday when she visited Sumas Prairie.

“She's like, ‘yeah, there's funding coming.’ But you know, like, we kinda have no money now,” he said.

The farm remains flanked by a number of gravel berms, built at the last minute during last weeks floods. Pumps and heater blare in the family’s gutted basement. Last week, all of those measures ultimately failed.

Still, without any other option, Meier said he’s readying heavy machinery to bolster the farm’s floodwater defences.

“All I can really do is make sure the cows are healthy,” he said. “Make sure they don't die.”

With files from Brendan Kergin