The discovery of a mass burial site on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School could lead to a fresh wave of litigation, but don’t expect anyone to go to jail.

That’s the opinion of Thompson Rivers University law professor Craig Jones, who said a lot depends on how the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc band decides to proceed with the burial site.

On Thursday, Tk’emlups Chief Rosanne Casimir issued a statement announcing the remains of 215 children had been located, using ground-penetrating radar, on the site of the residential school.

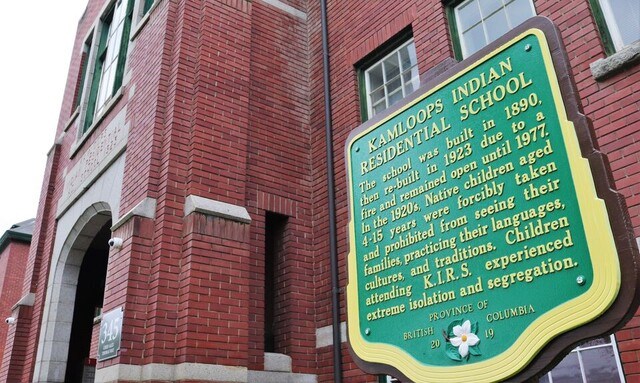

She said the find confirmed a long-held belief in the community that the school, which operated from 1890 to 1978, was the site of many undocumented deaths.

“I think the Truth and Reconciliation Committee estimated the proven number of deaths at residential schools was a little over 3,000, but I think everyone has always known that the number was probably much higher on account of undocumented deaths,” Jones told Castanet Kamloops.

“What this appears to be is, at the very least, evidence of a substantial number of undocumented deaths. Now, what happens with that is going to depend in large part on how much of the background of each of these victims can be discovered — and that’s going to depend, I think, on individual families coming forward with their own stories.”

Casimir said the band has been in contact with neighbouring First Nations about the discovery.

Jones said Tk’emlups officials will have to decide how to proceed.

“In the ordinary course, if we were investigating a mass grave in Rwanda or Mexico or the former Yugoslavia, then you would just have a sort of team of forensic experts taking DNA samples without much regard to the gravesite as anything but a source of evidence,” he said.

“Here, we have cultural sensitivities and very delicate protocols that may actually mitigate against finding out all that we can from the remains of the victims.”

Despite that, Jones said he’s confident the discovery will lead to a lot of litigation.

“It wouldn’t surprise me at all to see a fresh wave of wrongful death lawsuits premised on negligence and the failures to provide the necessities of life when there was duty to do so,” he said.

“I can definitely see that, and I can see this even if the individual graves aren’t the sources of much in further individual evidence. If they decide not to proceed that way, I think just the fact of their existence and the discovery is going to lend an awful lot of weight to claims of undocumented deaths.

“If a family reports that a child had gone to residential school in the 1920s or 1930s and never returned, and they’ve been told they died of some preventable communicable disease — which is probably the cause of most of these deaths — you have that evidence and then that will be bolstered by the very existence of these graves, even if you could never establish that a particular child was in a particular grave.”

Reaction to the discovery has come in from across Canada. Many online have called for action against those behind Canada’s residential schools — namely the federal government and the Catholic Church, which ran the Kamloops school for most of its existence.

While Jones expects to see plenty of lawsuits, he does not think anyone will face criminal charges.

“Absent the sort of individual evidence where you could attribute a particular death to a particular act or oversight, you’re not going to have a criminal case,” he said.

“Even if you do have a criminal case … you’re dealing with incidents where anyone who could be shown to be responsible, I expect very few of them would still be alive.

“We have to keep in mind that we have known, without a doubt, that thousands of children died in residential schools and most of them, or at least many of them, were buried in unmarked graves at the schools. What we have here is just a visceral reminder of that tragedy.”